|

The Illinois National Guard - Sixties StyleBy Bill MachotaI was born in 1942 in Harvey, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Dad never went into the Army because he worked at a plant that was manufacturing munitions. Mom died when I was seven, so Dad packed up my brother, sister and me and we moved to Chicago, where he had a much better chance to get a job. I grew up in the "Back of the Yards" neighborhood and lived there until 1965. You've all heard about growing up in the Fifties and it's all true, so there is no need to bore you. When all the guys became of draft age, decisions had to be made: join the Army, Navy, or Air Force - or sign up for six years in the National Guard. It was a split decision among the group I hung around with. In the early Sixties Vietnam was not on anyone's mind. Most of them chose the Army so in two years their obligation would be over.

Other than during the Korean War, the National Guard was pretty much like a sleeping dog. To fulfill that obligation, all that was required was once a week you went to a two-hour training meeting and once a year you went to two weeks at summer camp to do a little practice on what in my case was the artillery. In conversation with the old lifers in the unit I was in, they said, "Heck, nothing has happened here in twenty years!" Well, I don't think it took me more than two or three weeks before things started to "cook." It was in the middle of July of '63, before I was even inducted into the Army, that the unit I belonged to was called out for the first civil disturbance of that era. This disturbance was the beginning of the many civil rights movements before the King era. Granted, we didn't really go anywhere; we were just on call, but that was the beginning of many things to come.

It was early in 1966, with the escalation of the Vietnam War, that the government decided that the National Guard should take a bigger role in the defense of the country. That day at the armory when they picked who would remain with the old unit and who would be transferred to a combat-ready unit will always remain in my memory. It was a scary feeling, especially when you figured that there was no way a guard unit would go to Vietnam. When I told my wife that evening what was happening, all we could do was hope we wouldn't have to go to combat. It was at this time that I went from one two-hour meeting a week and two weeks of summer camp to getting transferred to a combat-ready unit and going for two full weekends a month plus the two weeks of summer camp. The whole idea behind this, of course, was to prepare us for a trip to Vietnam, and since I was in an artillery unit, we would be one of the first, other than reconnaissance, to be called out for this wonderful trip. 1967 proved to be another interesting year. Up through April, things were quiet. Then, on April 21, as we were getting ready to go out to celebrate my wife's birthday, a massive tornado hit the city of Oak Lawn. It destroyed part of a school and much of the community that lay within its path. Because of the massive destruction, it was a little too much for the local police to handle the area - to protect these homeowners from the looters and all the other riff-raff that would feed off somebody else's misfortune. We were called out the following day and sent to Oak Lawn to protect the property of all these poor unfortunate people. This tour of duty lasted five days. The upside of this tour was that the people were very appreciative of our presence. The downside, of course, was a week away from your home and family - and your job. A few short weekend call-outs and the year ended uneventfully.

It was fortunate that I worked for a company that accepted my obligation. I had heard from others that although they couldn't get fired, life was not all that great.

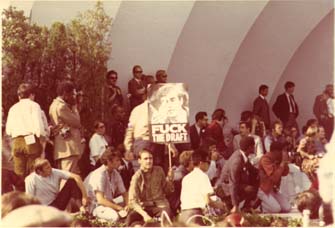

That afternoon, after my daughter was born and after being assured that everybody was fine and in good health, I made the trek down to the Chicago Avenue Armory. I had been told earlier that there was nothing really happening with our unit - that we were just on standby and waiting to see if we were going to get called out or be released. Well, by the time I arrived at the armory, they were deploying the whole unit to head out to the Grant Park area, so I grabbed my gear, threw it in a truck and on we went to Soldiers Field parking lot. As soon as we arrived at Soldiers Field we were called out to turn back a crowd that was coming down Michigan Avenue. That was a real interesting situation; there we were, in the middle of beautiful downtown Chicago, dismounting on Michigan Avenue and ducking ashtrays and bags of shit thrown from the hotel windows. This tour lasted up through the night of the Democratic convention when the march took place from Grant Park all the way to the Chicago Amphitheater, where the convention was held. Our job throughout this encounter was nothing more than to keep the crowds in an area and off the streets. The Chicago police handled any disturbances. No one was allowed behind the perimeter lines we set up. If they crossed (a few did, including reporters), they received the sting from the police. In our area of responsibility we were not on what was considered the "front line." The rest of 1968 turned out to be much better. With the de-escalation of the Vietnam War, we were taken off our two weekends a month and put on one weekend. It was great to know that we no longer might have to go to Vietnam. My obligation to the Guard ended in 1969, after serving in ten types of disturbances. It was a great way to go out: no riots, no tornadoes, no conventions, no weekends away from home.

Bill Machota is employed by ROTEC Industries, a construction equipment manufacturer.

|

It all started for me in the spring of 1963. Vietnam was now beginning to become a big issue; the Civil Rights movement had started. I had just been given a promotion and, most important of all, gotten engaged to be married. All of this, and I was ripe for a letter from Uncle Sam. I needed to make a decision: do I forego the new promotion, with the possibility of it not being there when I get back, and, just being away from my future wife for two years - well, I didn't think that was such a good idea. Because I had an obligation to fill, I had to do something, and what I chose was to join the National Guard. Four of us from our group all made the same decision, opting to keep our jobs and still fulfill our commitment to Uncle Sam. Unbeknownst to all were the events that would occur in the next six years.

It all started for me in the spring of 1963. Vietnam was now beginning to become a big issue; the Civil Rights movement had started. I had just been given a promotion and, most important of all, gotten engaged to be married. All of this, and I was ripe for a letter from Uncle Sam. I needed to make a decision: do I forego the new promotion, with the possibility of it not being there when I get back, and, just being away from my future wife for two years - well, I didn't think that was such a good idea. Because I had an obligation to fill, I had to do something, and what I chose was to join the National Guard. Four of us from our group all made the same decision, opting to keep our jobs and still fulfill our commitment to Uncle Sam. Unbeknownst to all were the events that would occur in the next six years. It took a few years for things to really get rolling, but when it did, it really hit the fan! During the next few years, a number of minor civil rights disturbances took place. We were called out so often that it became a joke and we would be called "Governor Kerner's Rent-A-Guard" - just like a Hertz Rent-A-Car.

It took a few years for things to really get rolling, but when it did, it really hit the fan! During the next few years, a number of minor civil rights disturbances took place. We were called out so often that it became a joke and we would be called "Governor Kerner's Rent-A-Guard" - just like a Hertz Rent-A-Car. Then came 1968 and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Most of us remember the massive rioting that broke out on the west and southeast sides of Chicago. Our unit was called out, after the first few days, to assist the police in controlling the rioters. Our first tour of duty took us to the southeast side of Chicago. I had a roving patrol on 63rd Street from Stoney Island to Cottage Grove, under the "El" tracks. Besides the looting that was taking place, which the police mostly handled, the sound of gunfire in the air just shook you to the bones. You had no idea from where these shots were being fired. Though our presence was pretty much a show of force, there were times when we had to dismount and control a group of potential rioters and keep the crowd levels to a minimum. We were on continuous duty for a total of seven days, with most of our time spent on the south side of Chicago, sleeping on the floors of the Sears store or the dime store, or wherever there was a convenient place to take a rest. The food and accommodations were marvelous!

Then came 1968 and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Most of us remember the massive rioting that broke out on the west and southeast sides of Chicago. Our unit was called out, after the first few days, to assist the police in controlling the rioters. Our first tour of duty took us to the southeast side of Chicago. I had a roving patrol on 63rd Street from Stoney Island to Cottage Grove, under the "El" tracks. Besides the looting that was taking place, which the police mostly handled, the sound of gunfire in the air just shook you to the bones. You had no idea from where these shots were being fired. Though our presence was pretty much a show of force, there were times when we had to dismount and control a group of potential rioters and keep the crowd levels to a minimum. We were on continuous duty for a total of seven days, with most of our time spent on the south side of Chicago, sleeping on the floors of the Sears store or the dime store, or wherever there was a convenient place to take a rest. The food and accommodations were marvelous! Just before the seventh day, we were relieved of duty by the regular U.S. Army troops. They were really happy to be there - a lot of these guys had just gotten back from Vietnam, thought they were going to be winding down - and here they were, in the midst of more gunfire! So, we left the friendly confines of the south side of Chicago and were instructed to go to the west side of Chicago where there was much more happening in the way of burning buildings, more looting and more gunfire. Since we were on a roving patrol, it took us through all the smaller internal areas of the west side of Chicago. It was not a pretty sight. It was hard to imagine, given the way we were brought up, that people actually could live and survive in this type of environment. Poverty reigned supreme. Some homes could hardly be called homes. It was as though everyone lived on the streets and only slept in their homes.

Just before the seventh day, we were relieved of duty by the regular U.S. Army troops. They were really happy to be there - a lot of these guys had just gotten back from Vietnam, thought they were going to be winding down - and here they were, in the midst of more gunfire! So, we left the friendly confines of the south side of Chicago and were instructed to go to the west side of Chicago where there was much more happening in the way of burning buildings, more looting and more gunfire. Since we were on a roving patrol, it took us through all the smaller internal areas of the west side of Chicago. It was not a pretty sight. It was hard to imagine, given the way we were brought up, that people actually could live and survive in this type of environment. Poverty reigned supreme. Some homes could hardly be called homes. It was as though everyone lived on the streets and only slept in their homes. Then came August and the Democratic National Convention. Things were happening in downtown Chicago that didn't affect me, but were interesting to read about. That was until the police and the hippies got into it with each other. So here it was: another tour of duty with Governor Kerner's Rent-A-Guard. It was at this time that my wife was pregnant with our daughter, Jill - and very close to her delivery date. Well, that morning, things started to happen with her, and I got a call from the Guard saying, "Okay, boy, get down here," and my wife was telling me, "I'm going to have the baby - let's go to the hospital." Of course, family comes first, so I called the first sergeant and said, "As soon as my wife has the baby and everybody is fine, I'll see you there."

Then came August and the Democratic National Convention. Things were happening in downtown Chicago that didn't affect me, but were interesting to read about. That was until the police and the hippies got into it with each other. So here it was: another tour of duty with Governor Kerner's Rent-A-Guard. It was at this time that my wife was pregnant with our daughter, Jill - and very close to her delivery date. Well, that morning, things started to happen with her, and I got a call from the Guard saying, "Okay, boy, get down here," and my wife was telling me, "I'm going to have the baby - let's go to the hospital." Of course, family comes first, so I called the first sergeant and said, "As soon as my wife has the baby and everybody is fine, I'll see you there."