Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=962

Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB) |

To mark the release of Winter Soldiers: An Oral History of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, VVAW member Kurt Hilgendorf sat down with author Richard Stacewicz.

|

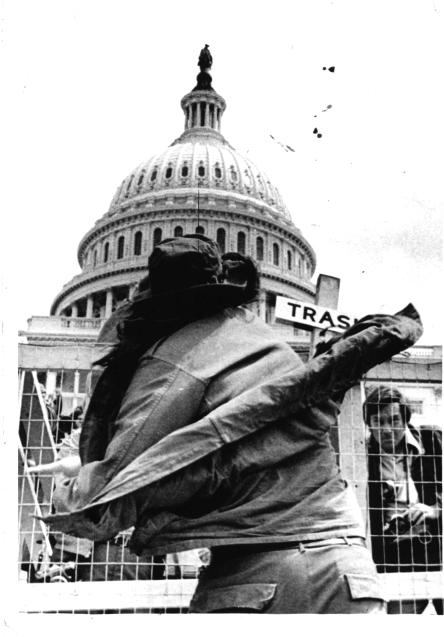

| Dewey Canyon III |

Your book is an oral history. Why did you choose this method? And how does this fact differentiate it from other books on VVAW?

When I started the project in 1992, I didn't intend for it to be an oral history. I knew after doing some preliminary research that there wasn't a lot of paper trail. This organization did not think of its legacy so they didn't save everything. There's stuff at the University of Wisconsin, there's stuff around that I went through, but it didn't reveal in great depth why certain decisions were made, why certain actions were taken, who actually decided these things. I knew I had to interview people. It was only through the process over the next few years of traveling around to various places interviewing people as I met them and then starting to transcribe them that I realized in the transcription process that their voices were much more powerful than anything I could write about what they said. The most powerful testimony they gave was in their own voices. At that point, about 1995-96 I decided that this made sense as an oral history. It's still much more powerful to actually read the words of people who experienced something than it is to read my analysis of it and then let the reader decide how they perceive what people have to say.

Why aren't there more oral histories done?

I'm a trained historian, and when I said that I would change it into an oral history, the first thing people said is that "that's not legitimate history" because what we rely on is documentation. "People's memories are faulty, how do you trust them, so you're not really doing history." The ironic thing is this is the way people have been chronicling their lives for thousands of years. Oral history is the first form. The Odyssey was spoken. Since at least the last 200 years in western culture, oral history is not seen as legitimate history. As a historian, if you want to maintain your status as a historian within that community, to do it [oral history] is kind of risky because you are demeaned by others who don't see it as real history. But I didn't give a shit about that.

The book came out in 1997, in an early limited run of about 5000 copies. There have been a lot of efforts over the last 10 years to get the book re-released. What was the process like?

When it was originally released, I went with a small publisher, Twayne that specialized in part in oral history and we had a verbal agreement that once it came out in hard-cover it would come out in paperback. But then they were bought up by Simon and Schuster and then Prentice Hall and the book came out under the imprint of Prentice Hall. And they decided that they wouldn't put it out in paperback, along with hundreds of other authors. I spent the next few years trying to get the rights back, and got them back in 2002. I put out feelers in 2003, and was very close with South End Press in 2004. I held off looking for other groups, and it came down to the final vote. What it came down to was that they wouldn't put it out because they didn't do this kind of book, although several people wanted to start doing that kind of book. What happened was that Joe Miller made contact with Haymarket Books last year and then I followed up after he started the process, and we started the ball rolling. They were very happy to put it out.

Was it poetic justice that the book came out with wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with the urgency of people in an anti-war movement telling their anti-war story?

Yeah there is a kind of poetic justice. The sad thing is that these adventures, these foreign interventions keep happening, so the book will be relevant for different periods of time. It works well with IVAW growing as it has been, and VVAW playing a critical role in that, there's a direct connection between the two organizations.

What has changed between the original book and the 10 years since, or is it the same thing?

They [Haymarket] wanted it to be the same. What's changed with the book? Nothing. We're now embroiled in another lengthy war to dominate another region of the world. That's changed. It wasn't that way in 1998. People didn't think we were involved in that, even though there were sanctions on Iraq and we were still bombing them on a weekly basis. The vast majority of Americans are now unhappy with what's happening, even if they cannot pinpoint exactly what's going on. That's similar to what was happening 40 years ago. Hopefully it will raise questions.

If you had to pick one story from the book that stands out as the essence of oral history, what would it be?

What really matters to me, in history in general, is the human dimension, which often gets overlooked. How are people affected by these trends? You can talk about wars, you can talk about tactics, but really, when it comes down to it, how is that human being who's living on that side of the bombs experiencing it. Often we don't get that, and oral history gives us a peek into that, some idea how people were affected by these things. Most people aren't going to leave massive tomes and diaries that will explain what they're going through. The only way we can mine that information is by talking to people. There are a number of stories. The main thing that sticks out in my mind is someone like Dave Cline, who had doubts about why he was going, felt he had to go because it was his duty, and that's pervasive throughout the stories. People felt that even if they had doubts about it, this was something they had to do. Or they were gung ho, ready to go. I don't think I would've gotten that information from reading different texts. I wanted to get a sense of who these human beings were. What they felt, what they thought, what they believed they were going to do, and then to see the transformation take place. Like with Dave Cline, it wasn't an immediate about face. It was a series of experiences that they had, in boot camp, and in the military and returning finally that led them to rethink what they believed, not just about Vietnam but about their place in the world and what was happening in the United States. Oral history allowed me a glimpse into that that I don't think I could've gotten any other way. Those stories resonate with that same pattern of change that takes place. There were only a couple of people, like Pete Zastrow, who entered into the war thinking it was wrong. But most really wanted to believe. I think the most incredible thing, what really struck me about these guys, was the question of the war is over, you've survived, and you've done your duty. Why the hell are you now spending all your time protesting? It really speaks to their commitment that they had before going in, but that continues on afterward. They really wanted to believe they had this role to play and were meant to carry it through.

Has your understanding of VVAW's history changed since the book came out? Has VVAW's work with IVAW, opposing the war in Iraq, VVAW's growth over the past few years – was that something that you would have foreseen? And did it change your perception of the organization?

My perception of the organization hasn't changed. Frankly, when I started interviewing everyone, looking at the records, and the women involved, these people are incredible human beings who continue to do this stuff. I thought the organization was on its last legs. I thought I was going to compile the information of an organization that is no more, and at least like the Abraham Lincoln brigade there would be a record of them. I never thought that they'd rejuvenate in this way, especially now that 7 people in the book are now dead. Even before the book came out, people were dying, Jack McCloskey and John Kniffin and others. I thought "wow, I'm glad I captured some of their voices before the organization disappears." And here it is, they're back, they're working with IVAW. I think the war has brought back people who are Vietnam vets and had stopped their involvement in the movement. It's all positive. I never would have guessed this.

A lot of Vietnam vets talk in schools and give their stories of what they've seen and what they've done. How would an oral history or oral analysis of what's going on in Iraq be effective now and 10 years from now?

I think it's effective because people who are young, 15 – 16 – 17, and possibly considering the military as a career, and I don't have anything against the military other than what they're made to do, need to hear from these folks who have been in. We're surrounded by propaganda about the glory of being in the military, especially young men. They need to hear other stories of people who have actually been there. That was actually one of the reasons I did this. I was teaching at the University of Illinois – Chicago when the first Gulf War broke out. It was the beginning of the semester, and I asked everyone in the class what they thought about the war. Most of the students in the class were for it. I started probing: "Why? What is it you that know about it? What is it that you feel about war in general?" A lot of the students, having grown up in the 80s, had grown up in an era when the whole historiography about Vietnam had changed dramatically. Vietnam was seen as a noble war but tactically flawed. The anti-war movement was a bunch of hippie, drug-using cowards. And I thought, "Wow, that really works. They grew up in this era when that was the dominant idea and it really works." Then I met Barry [Romo] and I thought, "I can try to inject this other voice of the veterans themselves so at least it will offer a challenge to the dominant ideology." That's what I think IVAW will do – they offer a challenge. We'll present this and hopefully people will get their hands on it and make decisions.

Why do you think young people don't understand Vietnam?

I think it's the education system, I think its culture, I think its film, and it's everything they've grown up in. The students I get now have no understanding of it. It's not that they can't, because once they do, they understand it much better and make the connections with Iraq. But without that historical knowledge, it's like Howard Zinn says, "it's like you're born everyday."

How do you see Vietnam vets' role in opposing the current war? Is there a unique role that Vietnam vets play in opposing a war like Iraq?

I see them primarily as a great example to Iraq war vets and Afghan vets. They speak to those vets in ways that I can't and people who haven't been through that experience can't. They have legitimacy in the eyes of current veterans coming back. Playing that role of working with them, helping them out is the key. I think Vietnam is so far away in young people's minds today that I'm not sure they can speak to a larger audience who would take them seriously.

You had an opportunity to go to Winter Soldier: Iraq and Afghanistan. What were your impressions of that action and how do you view the current generation of Winter Soldiers related to the previous generation of Winter Soldiers?

I see the current generation of Winter Soldiers in a much more difficult circumstance. Vietnam Vets Against the War was formed at a time when there was a great dissatisfaction with the war, there was a strong civilian anti-war movement both here and internationally, that supported them, that they could feed off of. Within the military, there was a great deal of resistance growing. There was a cycle of the civilian anti-war movement, the vets, and then within the military the military resistance that all fed off each other. I don't see that right now. One of the biggest reasons is that there's no draft. Everyone in the military now is a "volunteer." They have financial restrictions that prevent them from resisting, from speaking out. There is a whole culture of the military that has been segregated from the civilian population in a way that didn't exist 40 years ago, that makes it much more difficult to go against people who they may be very close to. I think it was great for them [IVAW] to get together. Now the main point is to keep on working, and actually make more and more in-roads into the military.

Do you see the possibility that there will be a shift in military policy as Iraq carries on, to where the resistance will grow?

Realistically, depending on where you start our involvement in Vietnam, but if you go back to 1956 to advisory stage, or 1963 with the big troop buildup, it took 4-5 years to coalesce and to really get this organization [VVAW] moving. It's happened just as quickly if not more so now. So now it depends on if whether or not we'll continue dragging this [war] out, if the organization keeps growing. There is disaffection. All the polls show among troops that they don't like stop-loss and don't want to be there. The atmosphere is similar, but they're not serving one-year terms and coming back. That's the main difference. They're in for a much-longer time and resistance is much more difficult than 40 years ago. But nothing's impossible.

We spoke earlier of Dave Cline, someone who did GI resistance and organizing when he came back – are stories like his, a regular guy who came back more powerful than someone's like John Kerry's who had access to power and prestige and upward aspirations?

Much more powerful to the audience I was looking for. I was looking for it to be a high school/college audience of young people who often feel powerless. But to see someone like Dave Cline, Barry Romo, Jack McCloskey, all these guys who were working class guys who can have such an impact on really changing the course of history. They can actually be causes of changes and not just be buffeted around.

Sometimes I'll Xerox a few pages from the book and have students read them. The reaction when young people read some of the voices is pretty powerful. I've seen some people really begin to question some of their own ideas. These are people who they can relate to. They're the same people. That's what's most important to me. If it does get picked up and people read it that it has that same kind of effect.

Kurt Hilgendorf is a social studies teacher at John Hope College Prep High School in Chicago and a member of VVAW national staff.