Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=959&hilite=

Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v38n2.pdf (20.2 MB) |

"Seek the help you need and deserve. It can work." This is what I've said to so many veterans who, like me, suffer from combat-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Over my four-decade journey from the free fire zones in Vietnam to the present, I got very good at recognizing the triggers that, two or three times a year, would precipitate a debilitating emotional crash. With my wife, Cynthia's, help, I decided finally to seek professional help after President Bush's invasion of Iraq in March 2003 sent me into a dark psychological pit of utter emptiness. I had health care at the time through my job so I began a course of treatment with a private therapist. Since my therapist had also been a Marine grunt who saw combat in Vietnam and shared my interest in Eastern philosophy, we were on the same wavelength. Eventually, the VA agreed with his PTSD diagnosis. I underwent nine months of intense talk therapy (without drugs) that culminated in a three-month medical leave of absence from my job. The experience was transformative.

Jung wrote, "One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light but by making the darkness conscious." Through the help of my therapist, I recognized the two warring inhabitants that tugged at my psyche: The first was the traumatized twenty-year-old soldier, and the other was the falsely empowered young man who took on an attitude of contempt for his own pain. To use a male-female analogy, the timid feminine voice felt the pain of the trauma and the tears flowed, and a moment later the harsh masculine voice immediately said to stuff it and quit whining. It was like those cartoon characters of the devil and angel that sit on opposite shoulders giving opposite directions.

In Vietnam, we used to say, "It don't mean nothin." It was a necessary lie then and most of us continued to live that lie for decades after we got back. My crash experience is like turning emotional cartwheels—feeling, stuffing, crying, being embarrassed, then berating myself; then starting over again. I did not understand it; could not explain it; could not control it. My crying like a baby so embarrassed me, I only felt safe in Cynthia's loving arms. This would go on and on until I didn't think I had any more tears left in me and the day had gone by.

Of course, for years I had also exhibited the typical external manifestations of PTSD including hyper-vigilance, startle response, agitation, emotional numbing, etc. I learned that PTSD is a form of depression. We use defenses to suppress traumatic memories and to mask the internal depression. Many vets medicated their pain with alcohol and other drugs. My drug of choice fit my near-Type-A personality. I became a compulsive overachiever bent on seeking constant approval from others—performance-based self-esteem; what a good friend called, "atta-boys."

My therapist said that the harsh boy had served to protect me from the poison of war and to help me develop a good life but that I was now mature enough and strong enough to take the next step and begin to re-integrate all aspects of my personality. We did this extremely difficult work together mindful that I should not use Vietnam and PTSD as a convenient excuse whenever reality did not match up to my expectations.

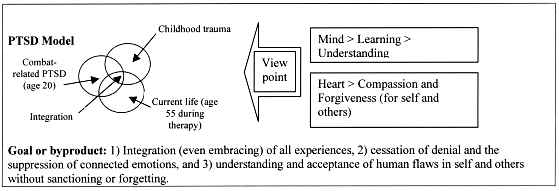

The following diagram illustrates my therapy. I worked harder than at any time in my life to understand at a fundamental level the inter-linking of the combat events that caused the PTSD with the childhood trauma that preceded them in my case (I hear of many vets whose therapy began, like mine, with childhood issues that had to be resolved along with the PTSD). Only until I could bring full compassion as regards the effects these past traumas had on me did I have the emotional maturity to forgive myself and others. Therapy has helped me with the lifelong process of integrating all of these experiences as being part of who I fully am, and to learn and grow from them.

PTSD Model: goal or byproduct: 1) Integration (even embracing) of all experiences, 2) cessation of denial and the suppression of connected emotions, and 3) understanding and acceptance of human flaws in self and others without sanctioning or forgetting.

I still suffer from PTSD but I have learned to better control it rather than be controlled by it. Most important to my healing process are the four decades of non-judgmental love, patience, compassion, and acceptance from my wife and daughter. They, along with our many family members and friends, opened their arms to me with a loving kindness that kept me on the path through the rich life I'm living.

|

Michael Orange is an environmental consultant,

author of Fire in the Hole: A Mortarman in Vietnam (www.amazon.com), and a long-time member of VVAW.