|

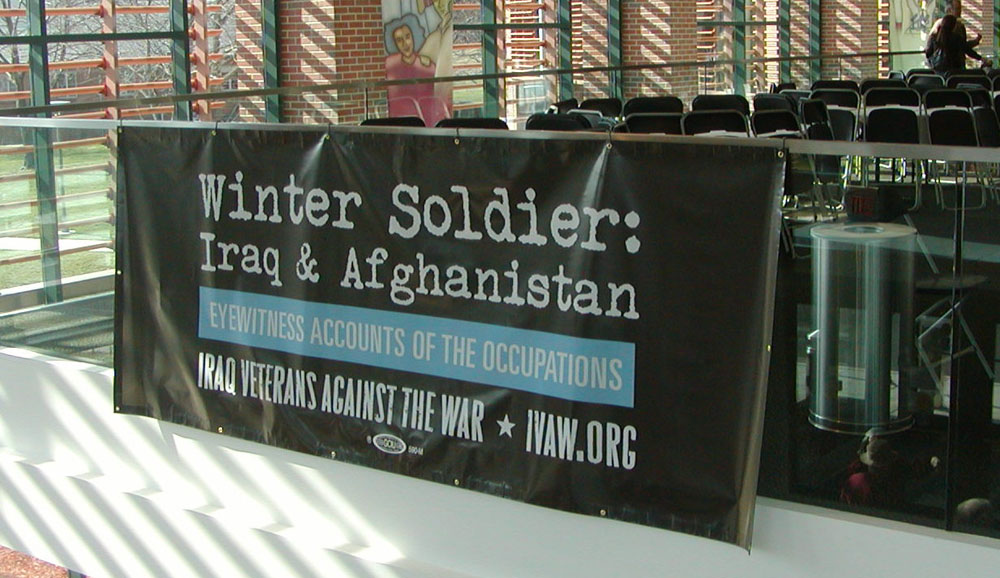

War is the AtrocityBy Richard StacewiczAfter describing the brutal murder of two Iraqi farmers, who were working their fields during curfew, with 50 millimeter machine guns and belt-fed grenade launchers and other incidents that contradicted the "rules of engagement," US Army scout sniper Garret Reppenhagen, ended his testimony by saying, "the truth of the matter is the war is the atrocity." From March 13th through the 16th, dozens of members of the Iraq Veterans Against the War along with their supporters in VVAW, Vets For Peace and military families gathered together in Silver Springs, Maryland to hold four days of hearings about their experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan. The purpose of the Winter Soldier hearings was "to show the true human costs of the occupation." Like their predecessors in VVAW who gathered in Detroit, Michigan 37 years ago, IVAW members sought to break through the media blockade that continues to restrict the public's access to the "Ground Truth" and instead reveal, the true nature of the war that is destroying Iraqi society.

The IVAW organized 13 panels made up of veterans, military families and various allies who presented a description of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (hereafter "Iraqistan") that sharply contradicts the official version of the wars described by Bush administration officials and their media lapdogs. They detailed the costs of the occupations on Iraqis and Afghanis, returning veterans, their families, and the nation. The roots of the Iraqistan debacle and the true lack of concern for the Iraqis and Afghanis can be found in basic training and deployment. Numerous testimonials recounted the lack of language and cultural literacy preparation in basic training. Iraqis and third country nationals, who worked for various contractors, were generally referred to as "Hajis." No distinctions were made between those who the troops had been supposedly sent to "liberate" and the "bad guys" they were to pacify. This attitude toward Iraqis was cultivated in basic training and permeated the military establishment. After summarizing the extensive nature of racism he encountered among his former commanders, former Sgt. Geoff Millard stated, "These things start at the top, not the bottom." Members of a panel on "Gender and Sexuality in the Military" further elaborated on the impact of basic training on not only Iraqi civilians, but on the brothers and sisters who served alongside their comrades. The heavy infusion of machismo and degradation of women and homosexuals that is often used to inculcate a fighting spirit among the troops devalued women and homosexuals in the military and exposed them to sexual harassment from their brothers in arms. Margaret Stevens, a medic with the New Jersey National Guard, argued that this kind of mistreatment of women is not necessarily the result of military engagement but happens "only in the context of these genocidal wars." Most of the veterans who testified described wanting to serve in Iraq to help the Iraqi people even if they had some doubts about their missions. Adam Kokesh, and others volunteered, "to do the right thing." Yet shortly after arriving in country, most realized that the Iraqis did not want them in their country. Jason Hurd, who served ten years in the US Army and Tennessee National Guard and served in Baghdad from November of 2004 to November of 2005, recounted a conversation he had with an Iraqi civilian that captured the feelings of many whom the soldiers encountered. When he asked the man, "Are your lives better because we are here? Do you feel like we are liberating you?" The man looked him in the eye and he said, "Mister, we Iraqis know that you have good intentions here, but the fact of the matter is, before America invaded, we didn't have to worry about car bombs in our neighborhoods, we didn't have to worry about the safety of our own children as they walked to school, and we didn't have to worry about US soldiers shooting at us as we drive up and down our own streets." The men and women in the military were placed in the untenable position of occupiers whose missions only inflamed Iraqi resistance. Numerous panelists described missions where soldiers were put under intense stress and pressure and were compelled to engage in activities that not only risked their own lives but those of the Iraqi citizens they encountered. Soldiers were put in what psychologist Robert Jay Lifton called "an atrocity producing situation" in which human beings behave in illegal and immoral ways they would normally reject.

Veterans described harassing and frightening Iraqi families and destroying homes often in the middle of the night. Scott Ewing, private 1st class with the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment who served in Telafar described trashing countless homes "yet found no evidence of foreign fighters or weapons caches." These were not isolated incidents but stories repeated over and over by veterans who had served in numerous places and at different periods of time over the past five years. This was standard operating procedure. Numerous testimonials recounted experiences where civilians were murdered because they happened upon US troops who were operating without clear and consistent Rules of Engagement. Veterans described the random shootings at passing vehicles, the destruction of a civilian occupied apartment building by an AC-130 gunship, the killing of women carrying bags of vegetables, the shooting of a civilian at a demonstration, and free fire zones where there were no friendlies. Everyone was deemed to be an enemy combatant. In order to cover up these atrocities, several of the panelists provided photographs of shovels and weapons they carried with them to place alongside the bodies of civilians they had killed in order to justify their actions. Former Marine Sergeant Jason Lemieux, who served three tours in Iraq, summarized the feelings of all who testified. He concluded that, "The Rules of Engagement changed frequently, contradicted themselves, and when they were restrictive, they were either loosely enforced or escalations of force, as shootings of civilians were known, were not reported because Marines did not want to send their brothers in arms to prison when all they were trying to do was protect themselves in a situation they had been forced into." The soldiers' primary concern in these wars, as it has been in previous wars, was to survive their tours, to protect their brothers and sisters in arms, and to return home. For many, however, the dream of a safe return home was deferred by the President's Stop-Loss program which turned many of those caught up in this program into "prisoners of war" as characterized by Sergeant Kristofer Goldsmith whose own experience with Stop-Loss led him to attempt suicide before his redeployment. The stress of continuous deployments is leading to increased levels of stress among countless young men and women in the military. Family members of soldiers who have succeeded in killing themselves provided moving testimonies of their children's demise. The true nature of the wars in Iraqistan was revealed by veterans whose duty was to escort convoys of trucks operated by contractors. Kelly Dougherty, a medic in the Colorado Army National Guard, served as a military policy sergeant from March 2003 to February 2004 escorting KBR vehicles from bases in Kuwait to bases in Iraq. She described how KBR trucks often broke down and how US forces had to secure them to keep them out of Iraqi hands. She described one incident in particular, when two fuel tankers broke down and hundreds of Iraqis from a nearby local village descended on the trucks to get the diesel fuel which they desperately needed. She recounted how she had been ordered to light the fuel in the tankers on fire and to destroy the vehicles. "Here we were burning fuel in front of Iraqi civilians who had to wait in lines for miles long just to get a little fuel for their stove or vehicles. It really brought home to me the complete irony and absurdity of our presence in Iraq . . . Putting our lives on the line and risking violence towards the Iraqi people to protect hunks of metal and then just destroying them at the end of the day. This happened so many times and we were so frustrated." Frustration, anger, fear and remorse were expressed by all who testified. "I just want to say that I'm sorry for the hate and destruction that I've inflicted on innocent people..." Jon Turner said. "I am no longer the monster that I once was." While there were strong emotions expressed throughout the hearings. The IVAW members see this event as a jumping off point. Rather than a culmination of their activism, it is just the beginning. "We are still soldiers," said Camilo Meija, "We are just not their soldiers anymore. We are the New Winter Soldiers." These new Winter Soldiers, like their predecessors, are now expanding their activism to reach out to active-duty personnel. Winter Soldier: Iraq and Afghanistan was eerily reminiscent of the first hearings held by Vietnam Veterans Against the War. What is clear, is that America's imperial appetite has not been sated. While the occupation on the ground in Iraqistan mirrors in many ways the circumstances in Vietnam, the military has changed. The resistance among active-duty personnel has not reached the proportions attained in Vietnam. It was this phenomenon that ultimately led to the end of direct US involvement in that conflict. Today, however, enlisted personnel serve for completely different reasons and in altered circumstances. Soldiers are "volunteers" rather than draftees who serve for primarily financial reasons and are rotated in and out with their comrades. The ties they develop with their fellow servicemen and women are deeper and longer lasting. They often live on or near bases and are much more immersed in the culture of the military. While numerous polls and increased levels of PTSD among returning veterans show that the level of disenchantment with the occupation of Iraqistan is growing, reaching out to active-duty personnel will not be easy. The military establishment has changed its structures since the end of the Vietnam War to forestall a new rebellion among its personnel, so too must this new generation of veteran activists develop new tactics to reach out to their brothers and sisters. Members of VVAW and the civilian antiwar community will play a crucial role in supporting their efforts to bring these wars to an end. Only the troops can do it. Richard Stacewicz is a Ph.D. in history, author of Winter Soldiers, and Professor of History and Social Science at Oakton Community College in Illinois.

|