|

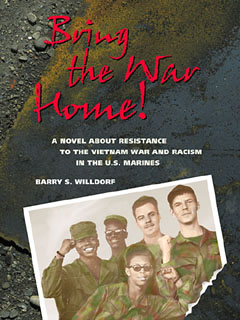

An Interview with Barry WilldorfBy Jeanne FriedmanBring the War Home! Jeanne Friedman interviewed Barry Willdorf in Oakland, California on January 5, 2002. Excerpts of this interview follow: JF: Barry, you are now a practicing attorney in SF. In 1970, with your wife Bonnie, as a new young attorney, you went to Oceanside, California, home of Camp Pendleton, to serve as an attorney on a GI Project, known as MDM (Movement for a Democratic Military). You and Bonnie had been active in the student anti-war movement at Columbia University and shortly after you graduated from law school you were hired to represent GIs for a wide range of civil liberties issues related to anti-war activities and the racism of the military, as well as direct attempts by soldiers to get out rather than be shipped to Vietnam. Tell us about the military system you confronted. BSW: These were the middle years of the Vietnam War. The student movement made it OK to protest the war. Now, the opposition was spreading into the military rather quickly. GIs were beginning to openly speak out against the war, to produce underground newspapers and to participate in demonstrations. Because, unlike prior wars, GIs rotated out of the conflict in 12-13 months, they were coming home in large numbers and telling their stories to an increasingly upset population. They had credibility because they couldn't be written off as shirkers, draft-dodgers or privileged students. The brass had no experience handling this kind of protest, so they came down pretty crudely with retaliatory measures and looked for whatever they could to write up dissident GIs and try to give them bad administrative discharges (UDs - undesirable discharge, they were called), or to court-martial them. This was an attempt to silence them or discredit them. That is why it was so important for them to have access to non-military-officer lawyers. And, by the way, Jeanne, I want to make a pitch for the guys, many of them Vietnam combat vets who have been living with those bad discharges for the past thirty years. They didn't get amnesty as did the draft resisters and it is time to put that right. It is just plain discrimination and it affects their ability to get good jobs and sometimes professional licenses. It is an injustice that ought to be corrected. JF: Camp Pendleton was the primary West Coast base for the Marine Corps, and, as was happening at other bases in cities where GIs congregated when off-base, there were coffeehouses as well as direct GI organizing projects. How many GI organizing projects were there between the late 60s and the end of the war in 1975? BSW: I estimate that there were about 15-20 in the U.S. at any given time and maybe 5-6 abroad. There were fewer than a dozen staff lawyers who were doing what I was doing full-time. Unfortunately, a lot of people didn't recognize the need or the potential that the GIs had for ending the war by getting the message to the farms and towns and factories where students would never go. JF: In this book, you created Eric and Emma as a husband and wife team who together confront all kinds of issues raised by this attempt to make change in what we called "the belly of the beast." Barry - set the stage for us - what changes were going to happen to Eric and Emma? BSW: Eric and Emma are former student radicals. They have the idealism of the peace movement and the commitment to volunteer their time to the cause of ending the war but they really have no idea who the GIs really are. There was a lot of stereotyping going on at this time, both ways. Now they are going to meet real people - Marines who have recently fought, who know people who died and who have killed, guys who have been seriously affected by their experience. They will meet black Marines who are not afraid to put their lives on the line to oppose racism in the military. And they will meet Marines who are still dedicated to the war and the Corps. Idealism crashes head-on with reality and that nearly destroys Eric and Emma's relationship and it changes their sympathies to include vets. JF: I'd like you to share with people what it felt like to come to Oceanside, to what some might have viewed as a romantic assignment - confronting the enemy. What did Eric and Emma actually find?

JF: I resonated with your description of the kitchen - not so different from many other movement collectives, especially ones that were consciously or unconsciously breaking with "bourgeois" norms of cleanliness. Tell us what that kitchen looked like. BSW: Here's an excerpt from my book about that: The room was pungent with the acrid smells of festering edibles. On the left was a sink, burdened by a mound of filthy dishes encrusted with the detritus of meals long past. Against the far wall an antique Frigidaire hummed loudly as it waded in a puddle of meltwater, the result of habitual neglect of defrosting. Opposite, an ancient four-burner gas stove bedecked with many-layered remnants of burned and spilled culinary efforts harbored a blue metal coffee pot with a cascade of brown vertical drippings permanently baked into its lacquer. In the very middle of the room a splintery spool table, six feet in diameter, dominated, like an altar to sloth, on the sticky, discolored black and white checkerboard of linoleum. JF: Given the dramatic changes that Eric and Emma were personally going to go through, tell us what GI movement organizers across the country found so compelling about working with veterans and active-duty GIs? There are many people here today who shared that experience with you and with me. I found especially moving your telling of what we might call the Marine Story - the very heart of what Eric and Emma were doing in difficult situation in right-wing Oceanside. BSW: Jeanne, many of the civilian organizers were vets. They were able to coax real feelings out of the GIs. It was a first step in getting many of them to deal with trauma that could make them time-bombs if they kept it bottled up. Here is one of my favorite passages in the book. Many of the vets whom I have talked to are really moved by it and have come up to me and told me that I put into words things that they wanted to say but couldn't bring themselves to say out loud. I'm going to let this passage speak for itself. This is why I was there. This is what motivated me to defend these guys who were serving their country, and why I stayed at it until the war was over. You ain't been there yet. You don't know, man. I didn't know shit about the racism part 'til I got into the Suck, man. But then I began to notice how they were always putting the blacks into the shit details. But that kind of shit don't sink in right away, 'cause a lot of the brothers got an attitude, ya know. And it takes time to get the picture. So I figure it's like retaliation, OK. But then, I can't help noticing how we treated the ARVN. You know, they ain't got all the muscle we got, but they been fighting a long time, and they ain't gettin' no respect. Sometimes they take ten times the casualties we do, but the first guys to get medevac'd out are us. And there's hostility. We're always callin' Charlie gooks and such, but if Charlie's a gook, then so are they. Even the brothers are calling them gooks, like they can't see past racism against blacks to the racism against the yellow man. An' what the fuck did I know, man, I grew up in a place where the only colored people I ever heard of were the black folks we saw on TV, like Rochester and Amos and Andy, and the only fuckin' yellows we ever seen were the ones that ran the laundry or maybe some Chinese restaurant in Albany. Yeah, we're riskin' our lives and all, but we ain't the heroes that some folks want us to be. We got the planes and we got the artillery and we got the armor. But we also got R&R and are out of there in a year. Them ARVN and, yeah, the VC too, some of them been fightin' five, ten years. Lost all of their family. Got nothin' to go home to but a burnt-up patch of jungle. If we're heroes, what the hell are they? And then, when we take a hamlet, who the fuck knows? Maybe the locals are VC and maybe they ain't. Who's goin' ta take a chance, get his ass blown off? We gotta destroy it. So ya end up callin' in air strikes on some shit-hole, piss-poor village full of rag-covered, scarecrow peasants. But hey, after a while you start to see all this shit different. How it's all crazy and mixed up, and it changes you inside. None of it makes any sense, 'cept surviving. An' that's a fuckin' good reason to blow some smoke or drop a tab or shoot a bit of smack 'cause the whole thing's fuckin' insane. 'Cause ya don't want to think about what you're doin' and just want to survive. That's what it's like, man. But for me, after a while, surviving didn't seem all that fuckin' important anymore, after I added up the stuff I'd been doin' to reach that objective. Maybe some guys can forget, or think they can forget. I ain't about to speak for them, but I can't believe that a whole lotta them are ever gonna forget, and in the end, down the road, they're gonna feel sold out one way or another. I just hit that place maybe sooner than some. We stick up for each other under fire, and that's the best of it. We're all brothers on that score. I'll remember that too, the good stuff. But how we got there in the first place and the shit we did while we was there, well, good luck to the guys who can forget that. Good fuckin' luck. JF: Everyone who was involved in anti-war organizing in any way during the Vietnam war will remember overt and covert surveillance and the planting of informants and provocateurs. As a lawyer, Eric was close to that situation on one prominent occasion in the book - Barry will you tell us what Eric learned and how he dealt with it? BSW: There is a scene in the book where Eric discovers that one of his clients is an informant. He also learns that this Marine is informing on another one of his Marine clients. He learns about this in a confidential communication that, ethically, he is bound not to disclose. But if he plays by that ethical rule, he will be permitting harm to another of his clients. Eric has no time the sit back and debate the fine points of the conflict. He must make a split second decision that may save one of the GIs at the expense of the other. It is one of many twists in the legal plot that I, as a lawyer, find interesting. At another point, Eric has to argue the exact opposite side of an issue for one client than he did for another. I got the inspiration for that from an old tale about Abe Lincoln, who was a railroad attorney before he got elected to office. One day, in the morning he argued an issue for the railroad and in the afternoon, he argued the same issue, but on the other side for an injured worker. When the judge, who had ruled for him in the morning asked why he shouldn't rule against him in the afternoon, Lincoln declared, "Because this afternoon, the worker has a better lawyer." Or so the story goes. JF: In your book, Eric and Emma are coming to grips with a host of contradictions including issues of race and gender. Understandably, Eric has a different slant than Emma, who is drawn to the women members of the collective in a way that Eric cannot be. I think it's not too much to say that Eric's manhood is threatened by all these strong women (who are, of course armed!). Will you share with us a passage in the book that sums up Eric's strengths and weaknesses? BSW: Well, it's interesting that you mention this issue. Every time I read passages from my book on gender conflict, I get opposite responses from the men and the women. Men love it when Eric tells off Emma and women cheer when Emma gives it to Eric. I just get a kick out of all the shit that this passage stirs up. "Did you notice how Joanie backed off on her attacks when it came to criticizing Clayton and Cookie?" I remarked dryly on our return to the motel. "She's ready, willing, and able to bust a white guy's butt even though he's a vet and just got shot. But when it comes to criticizing a black for breaking rules or for blatant sexism, she can't even whisper a criticism." Emma stared over at me. "Go easy, Eric," she said shaking her head. "Dealing with a multiracial organization requires diplomacy. Something you're not too expert on." "Yeah," I conceded readily, "I guess that's true. I just go at things the same way for everybody, even if it pisses people off. But Joanie comes off like a guilty liberal dealing with the blacks. They can see right through her double standard, and believe me, they don't respect it." "And I guess you think they respect you?" she challenged with a shake of her head. "Naw, Emma, I don't believe that. I don't believe Cookie respects me. But that's the result of her own racism. She can feel however she likes about me, but what I say isn't going to change because of her attitude. And her attitude isn't going to change based on what I say. As far as I'm concerned, if she doesn't like my opinions or what I say, she can go fuck herself, because I don't respect racists of any color." "You know, Eric," she observed, "you seem to have alienated two out of the three women in this collective in only one day. Have you ever considered that you might have a problem getting along with strong women?" "Well, I get along with you," I said, driving through a red light and forcing her to white-knuckle it. JF: Thank you, Barry. One last question, what motivated you to write this book? BSW: I worked on this project for more than six years, mostly on nights and weekends because I have a day job. Basically there were two reasons. First, no one has written a novel about the GI movement. I wanted to do a novel specifically so that I didn't have to get bogged down in petty sectarian squabbles about details: who said what to whom and who made or didn't make some crucial commitment. I wanted the story to be free of the small stuff and to force people to focus on the big picture - that there were thousands upon thousands of GIs who came home from service and made a difference in changing the hearts and minds of the American people. A lot of leftists take credit for ending the war these days, but for my money it was the GIs that did it. That's a hell of a story, really. After they came back from the war they served their country one more time by saving their younger brothers and cousins and neighbors from what they experienced. I wanted to salute them and pay them a tribute, while writing a basically accurate account of what it was like to participate in this effort. Second, I wanted to document the crazy times we were living in then. We have a lot of nostalgia junk out there about hippies in headbands and bellbottoms, wasted on weed. Saying "dig it" and stuff like that. Spitting on soldiers returning home. But that's all Hollywood wants us to get. All form and no content. I want people to know that there were progressive, anti-war people who supported the troops and wanted them not to go and to come home safely. I want people to know that some of us did what we could to help them when they needed help. Not just back-slapping, buy-you-a-beer, kind of support but we were there to do our best to get them the benefits and discharges that that they were entitled to. There are some folks out there today who have the GI bill, homes, education, health care, because I and some other committed people stood up and supported them. I consider our service to them to have been an honor and a privilege and I wanted to get that message across.

|

BSW: The MDM headquarters they arrive at had just been shot up by right-wing vigilantes called the Minutemen. In the book, two people were wounded. Actually, the fact was that the house that Bonnie and I went to in Oceanside was machine-gunned a few weeks before we got there and one Marine was wounded. The place was sandbagged. We had to have a 24-hour armed security watch because the police were very hostile and would not come if we called for help. They would only show up if they thought there was a possibility they could arrest us.

BSW: The MDM headquarters they arrive at had just been shot up by right-wing vigilantes called the Minutemen. In the book, two people were wounded. Actually, the fact was that the house that Bonnie and I went to in Oceanside was machine-gunned a few weeks before we got there and one Marine was wounded. The place was sandbagged. We had to have a 24-hour armed security watch because the police were very hostile and would not come if we called for help. They would only show up if they thought there was a possibility they could arrest us.