Download PDF of this full issue: v34n1.pdf (11.3 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v34n1.pdf (11.3 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=420

Download PDF of this full issue: v34n1.pdf (11.3 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v34n1.pdf (11.3 MB) |

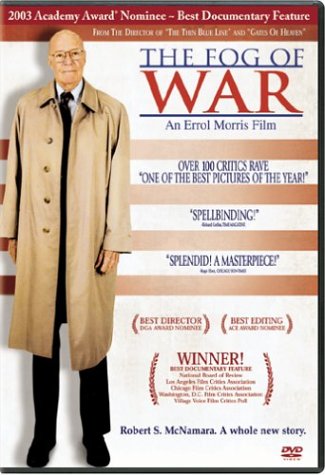

Erroll Morris' documentary The Fog of War is a good and important film, but not for any of the reasons that brought it acclaim. Excellent camera work, effective use of archive material and a willing, open subject make for a telling portrait of the ideology that fuels US militarism. In talking so openly about his life and times, McNamara doesn't really shed any new light on US policy, but rather unwittingly proves a range of leftist theories about networks of elite men generating chaos in corners of the world. The blurbs and mainstream hype around the film return to Morris' questioning regularly and credit him with pushing McNamara into "compelling territory," but in fact, Morris has little influence in steering the conversation. Apart from a therapeutic comment — "We're going to have to approach Viet Nam at some point" — he can't really control McNamara in his didactic approach to autobiography. Fortunately, he doesn't really try, and, perhaps realizing who he is dealing with, just lets things roll.

|

McNamara's autobiography is the spine of the film, supported in places by what Morris has posited as 'Eleven Lessons.' The lessons are phrases that appear glib when held up against the events within which they're contained; comments such as "empathize with your enemy" in the context of the Cuban Missile Crisis (where it deterred conflict) and the Viet Nam war (where its absence inflamed conflict).

Every historic event of the 20th century, of which McNamara was apparently an important part, is a necessary lesson in the two-sided nature of meaning well. As he runs through his resume, with a grating Ivy League jocularity we become keenly aware of the infrastructure of American militarism, with its network of brainy decision-makers, corporate contracting and military hawks. His description of his work in World War II proves Chomsky's Viet Nam era dissent on the complicity between US war makers and elite educational institutions. And as Morris brilliantly superimposes the names of US cities over Japanese death tolls, McNamara talks about the firebombing of Tokyo as a result of research into "military effectiveness." The sequence ends, perhaps chillingly to some, with him admitting culpability as a war criminal. It might arouse sympathy if it doesn't occur to you that we all know full well he'll remain immune from such charges.

The more McNamra talks, the more he is a portrait of the armchair general — knowing and wise in the ways of the battlefield and solemn about the lessons learned. All the while, "war" is some mysterious and compelling problem, like a piece of complex mathematics to which no one has found an answer.

Though he "approaches" Viet Nam and US policy in the 1960s slowly, Morris uses taped conversations between LBJ and McNamara to great effect. And while McNamara talks in such a way that insists he wanted withdrawal, not expansion, the blind allegiance to doing the right thing and maintaining military authority leave us dumbstruck. Any debate on whether contemporary policy in Iraq is "another Viet Nam" is quickly settled listening to LBJ's Texas drawl; we hear Bush on freedom and security and, seeing Morris' shots of McNamara's 1965 analysis, the word "Terrorism" surfaces on the page like detritus thrown from an explosion. The Gulf of Tonkin incident is clearly exposed as a fake by Morris (with archival tapes) but McNamara dodges the criminality of escalation with a rhetorical oddity: "Belief and seeing are both often wrong."

On nearly every major matter from the era, McNamara dodges with a combination of rhetoric and mea culpa. The toxicity of Agent Orange was completely unknown to him and he would never have knowingly authorized it; he was always pushing for withdrawal, going so far as to confront the President; on the matter of responding to public protest with the military, he claims 'the guns weren't loaded. And I was never going to order them to be" (apparently this information never made it to Ohio.) In one moment of grand delusion, he seems to equate his own conscience with that of Norman Morrison. All of these things add up to a portrait of the infrastructure of empire, though McNamara seems simply to be giving an insider's account of difficult decision-making. At the start one is overwhelmed by his smug didacticism; after two hours he's an eighty-five year old man soaked in regret, attempting penance. As the film ends, with a note that in 1967 McNamara moved from the Pentagon to the World Bank, we might consider the noblesse oblige of twentieth century development and contemporary global inequities. The lesson being that history doesn't repeat itself — ideology repeats itself; history follows.

This is a good film, particularly for the university classroom. But it is not a simple lesson in 'war is bad' rhetoric — though it is being hailed as such. It is a chilling portrait of a delusional elite who, when asked if he were "author or instrument," stated, "I was doing my duty."