Download PDF of this full issue: v53n1.pdf (37.7 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v53n1.pdf (37.7 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=4168

Download PDF of this full issue: v53n1.pdf (37.7 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v53n1.pdf (37.7 MB) |

Well into my recruit training at Great Lakes, the time for job classification came around. It seemed that Navy Journalism school was not in the cards for me, since I never learned to type, and this was a prerequisite. So, the counselor says to me: Why not go for Radioman, since your radio scores were very high? I was not interested in that option.

Then, he says, how about a Communications Technician (CT)? "What does a CT do?" I asked. He read from a prepared statement that described the duties of a CT(A). I would be providing clerical support to the worldwide communications system of the Navy. This would also require a security clearance. That got my attention, with trench coats, microfilm, and funny little pills dancing in my mind. I would be part of an elite group, the insiders. Kinda silly, huh?

So, following basic training and a couple of weeks on leave, I went off to "A" school at Bainbridge, Maryland in late July 1961. The training included typing skills, working with personnel files and other documents, and basic clerical work. Not much about the secrecy aspect.

The quest for prestige and insider knowledge that motivated many of us to become CTs also led us to try for the language program. We were eligible to take the Foreign Language Aptitude Test (FLAT). On the day of the test, we filled out a "dream sheet" as to our preferences for language and place of study.

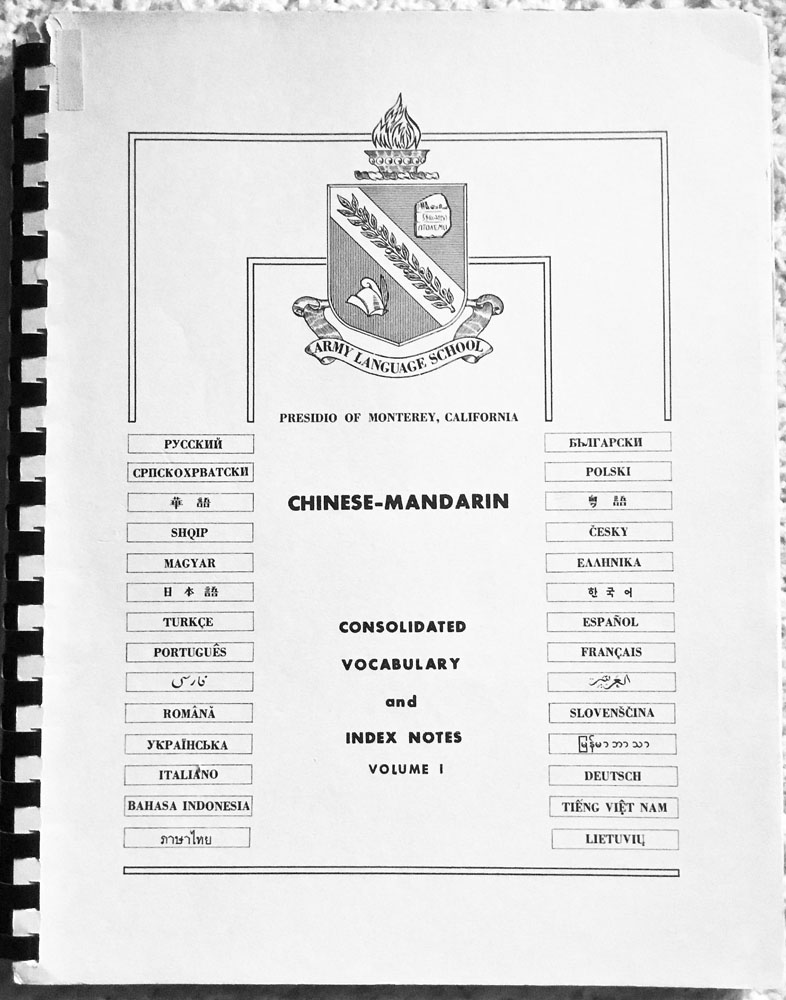

Eventually, during the final week of school, we received our orders. I found out why they called it a "dream sheet." I requested to study Russian, Polish, or German; I was assigned to study Chinese-Mandarin. I requested to study in Washington, DC; I was assigned to Monterey, California.

Well, I always wanted to see California.

After two weeks leave, I headed for California in late October. After arrival in Monterey, I reported at the Naval Postgraduate School, the site of an old hotel. This was my introduction to the "relaxed" Navy. Obvious military presence was minimal and civilian clothes seemed to be the "uniform of the day." I handed in my orders and was disappointed to learn that this place was not my actual duty station. I was to report up on the "hill," at the Presidio of Monterey, where the Army Language School was located.

When I arrived at the school, I found even more relaxation in the military presence. The only uniformed people in the barracks were those on duty. The term "barracks" doesn't fit here, at least in its usual connotation. Students were assigned to two-man rooms, each with two desks, two fairly comfortable bunks, and two six-foot lockers per student, one for uniforms and one for civilian clothes.

This was certainly another step up from recruit training. I felt a sort of culture shock. After everything learned through basic training, an assignment to a school like this can blow it all to pieces. In addition, this was an Army post; Navy personnel were in the minority. Even the Army students did not have to put up with most of the crap handed out in the "normal" post.

We were all there on orders, and it was our duty to learn one of the nearly thirty languages offered at this school. So, it seemed that the relaxation of normal military practices was meant to allow more focus on studies. Even the regular uniform inspections were somewhat farcical. Army officers knew very little about inspecting the uniforms of Navy or Marine personnel.

We were in class five days a week, six hours a day. A normal class day looked like this: reveille at 5:30 am; muster outside the barracks at 6:00 am; breakfast and room clean-up from 6 to 8:00 am; class at 8:00 am; lunch from 11:00 am to 1:00 pm; class from 1:00 pm to 4:00 pm. From 4:00 pm to 6:00 am the next morning, we were on our own. There were no duty assignments for students. There was no such thing as a bed check or the need for liberty passes. There were no gates, no guards, and none of the stock military base practices. On weekends, we were totally free….of course, we were expected to study three to four hours each night. No one checked on us.

The classroom situation also reflected a relaxed military presence, though we were in uniform. Each classroom had no more than nine students, including enlisted men, officers, perhaps an officer's wife, and once in a while a mysterious civilian. All the instructors were native speakers. In my case, most of the instructors were those who left China in 1949. All in all, this was a pretty open atmosphere, very conducive to study and the development of friendships. The question of rank and privilege seldom played a role.

However, the situation did lend itself to some amusing heated competition: officer vs. enlisted; officer vs. civilian; wife vs. husband; enlisted vs. enlisted. Who had the better pronunciation? Who had the greater vocabulary? Who could write Chinese characters most like a native speaker? Invariably, enlisted personnel would be top of the class, which made for mild "confrontations" when an officer could find a reason to pull rank.

While at the school, I learned a little more about the job of a Communications Technician. The Naval Security Group (NSG), the naval communications arm of the National Security Agency (NSA), had a liaison office on school grounds. The time came for me to prepare for advancement exams, and I was allowed to study in this office. Materials were not to be removed from the room. The windows were covered over and barred. The study materials were kept in a back room with a heavy vault-like door.

Here we learned the "official" job description, the vague answer given if ever questioned about what we did. It didn't say much more than what I was told in basic training. Still, it fed into that feeling that we were special, part of the elite, people who knew things no one else could know. We were cautioned that everyone in Monterey knew that "special" people were being trained at the language school. If there were any persistent questioners, we were to report them to the NSG office for investigation.

We were also told not to get too friendly with the instructors, for not all of them had been thoroughly checked out by the Defense Department. Rumors of "Agency" informants being planted in each class also served to heighten a sense of mistrust and paranoia.

Another factor that added to the sense of insecurity was the fact that, every so often, someone would be called out of class and informed that their security clearance did not come through. They were then immediately transferred to the so-called "regular" service. They were never given a reason as to why they were denied a clearance. We never knew who might be next.

Eventually, I spent eighteen months at the school. Though my original assignment was for a twelve-month course, the opportunity for advanced study in Chinese presented itself. I volunteered for an additional six months, realizing that this might increase my chances of actually being sent to Taiwan, where I could really use the language. This would also allow me to spend more time in Monterey, a place I was becoming quite fond of.

My time in Monterey affected my values and attitudes, as did the intensive study of the Chinese language. Monterey was an artists' community, and although Fort Ord was just across the bay, military life did not seem to belong. The overall atmosphere, mixed with the study of an "abstract" language like Chinese, made for the development of a more thoughtful, more existential perspective on life.

By coincidence, former Green Beret Donald Duncan spent time at Fort Ord around the same period. He describes Monterey in his 1967 book The New Legions:

"The area has an atmosphere (despite the number of retired colonels, generals and admirals) quite different from that surrounding Southern military posts—the result, I think, of the natural beauty, the traditions of the permanent citizens, and the lack of Southern tradition, chauvinism, and prejudice. Whatever it is, the newcomer has an almost irresistible urge to create and give of himself—a very unmilitary trait—and people who stay for any length of time want to paint, write, play an instrument, or at least engage in philosophical dialogue. I found myself eventually spending more time in discussion and in reading books not connected with the Military." (p. 196)

Because of my extended study of Chinese, I got orders for duty with the Naval Security Group Detachment (NSGD) at Shulinkou, outside Taipei, Taiwan. I guess the Navy figured they had spent so much money and time training me, it would be a waste to send me to Japan or Okinawa (where many of my classmates ended up).

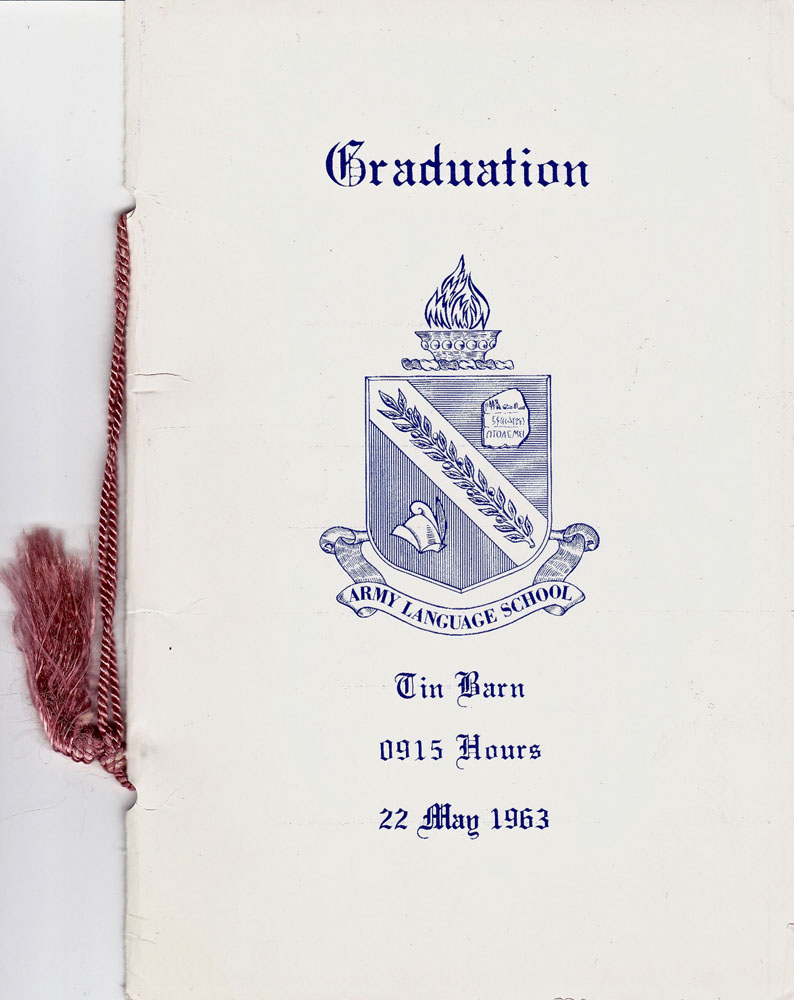

I graduated from the Army Language School sixty years ago, on May 22, 1963. Less than a month later, I arrived in Taiwan, on June 12th. I had now officially entered what I am calling "spookville." The next year and a half would change my life. I would become a Vietnam veteran.

Joe Miller is a board member of Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

|

|

|