Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=4115

Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB) |

From Richard Stacewicz's Winter Soldiers pages 358-362.

In December 1972, Barry Romo went to North Vietnam—the third such trip by a VVAW member. His experiences there reveal a great deal about the changes these men underwent as a result of their activities in VVAW. Barry Romo witnessed the Christmas bombings firsthand and received a strong impression of the American government's deceptiveness and its willingness to "bomb Vietnam back to the stone age."

What was the purpose of your trip?

To see what was going on there and be able to break the United States' media embargo. We could cut through all of the lies of the Nixon administration. We also brought packages and letters for 500 POWs.

We left New York, and on the plane was Telford Taylor, who was the chief prosecutor at Nuremberg; Joan Baez; and Reverend Michael Allen, assistant dean of theology at Yale.

I got there [Hanoi] three days before the Christmas bombing in December of 1972. They dropped more than [the equivalent of a nuclear bomb a day on Hanoi. In a 24-hour period, there would be two waves of B-52 strikes. They would lead with F-111s, who would come in below the radar. Then they would be followed by a combination of B-52s and Phantoms doing both strategic and tactical bombing. That was a freak. Because in October they had ended the bombing. Kissinger had said "peace was at hand."

We had to go down into the bunkers. I couldn't stand being underground. I think after the third time we went down into the bunkers, I talked to the Vietnamese and said, "I can't handle being underground." They said, "OK. Go to the bunkers, and after you've gone underground, then you can go back up—but you have to help and make sure all the other Americans get down there, because it would be an embarrassment if they were to die." So I would go help them get down in the bunkers, and then I would come back up.

Agence France-Presse was at the hotel we stayed at and they had a teletype machine. We would immediately see what the United States was saying. We would go visit someplace that was totally bombed and destroyed and see on the teletype machine the exact lie. It was like that. [Snaps his fingers.] Then we would issue a statement.

We went to Bach Mai hospital several times. The Vietnamese said that Bach Mai hospital was bombed, and Kissinger said there was no such thing as Bach Mai hospital—this is communist propaganda—despite the fact that Bach Mai was the largest hospital in Vietnam. It had been a hospital since French colonial days in the 1930s. We issued a statement that we had been there and it had been bombed. It was bombed more than three times. I got pictures of it. Then Kissinger changed twice. He said, well, it was an aid station. Then he said it was a hospital bombed by accident because there was military stuff around it. He went through all these changes.

We met with survivors of Con Son Island. We met with a group of women who had been tortured and raped on the island. They showed us their cuts and burns and physical problems and would tell us what it was like to be raped and tortured in American-built tiger cages.

Con Son, off the southern coast of South Vietnam, was used as a detention center by the South Vietnamese government; "tiger cages" were 4- by 5-foot cells in which political prisoners were held. The women Barry Romo met had peacefully protested against the war.

We visited POWs who had been bombed. They were incredibly freaked out because they thought the war was coming to an end and they were going home. All of a sudden, the bombing started again. "Am I going to be here five or six more years?" They may have come home and said one thing, but it was real interesting what they said while we were talking.

There was a committee of anti-war POWs. I put in a specific application to meet with them. We weren't allowed to meet with them. We only could meet with right-wing POWs. I think that they said, "If we let you meet with the anti-war people, they'll say it's a total propaganda trip. If we let you meet with people who aren't anti-war, they can't say that."

The Vietnamese were very leery of the humanitarian stuff. At first, they allowed the United States to send all kinds of goods to the POWs. They had this whole display of stuff that the United States, through humanitarian aid, had tried to send. Inside the toothpaste tubes, they had monitors and electronic devices and razor blades, and hidden wire saws. Very crude and stupid things, but it didn't surprise me because they (the United States military] were so racist: "Oh, these silly little gooks won't never know what's going on." They let stuff be sent if it was sent through the anti-war movement. We constantly got stuff in.

We could go walking totally free every day. In fact, our Vietnamese guides emphasized that they wanted us to go walk the streets alone so that no one could say that we were guarded. One time, we were walking and a little kid saw my VVAW button and flashed a smile, riding his little bike. Someone on a past trip had given him a VVAW button. He waved and showed it, and Baez freaked out: "Look, he's got a VVAW button."

Then we went to the Army Museum in the center of Hanoi. There was a glass case full of international gifts, and right in the center of the case was a Vietnam Vets Against the War button. That was pretty incredible.

What effect did all of these experiences have on you?

I was freaked out because here I am in the center of Hanoi, and I killed Vietnamese, and now not only that but the United States is trying to kill me, So where do you go from there? I also didn't feel like other people saw what I saw. When we saw the POWs, Telford Taylor, Joan Baez, and Michael Allen showed more compassion and love for the Americans than they did for the Vietnamese who were getting bombed. It really bothered me—not that I like to see a POW. I was a former soldier; my God, my nephew was killed in Vietnam. I knew what it was to cry over dead Americans. Seeing live Americans didn't bother me. If I had seen dead Americans, maybe that would have been too much.

What bothered me was that I was watching Vietnamese being slaughtered by our government. Going into workers' quarters where pieces of bodies were lying all over the place was a lot worse than seeing a person totally well walking to a press conference and feeling disoriented.

One day they held a party for us, and there were government ministers who came. They had made all this food and we were eating and drinking, and finally, I had the equivalent of a mental breakdown. I started to cry. The Vietnamese stole me from the Americans and took me over to a corner. They calmed me down. They surrounded me like mother hens around a baby chick and started talking to me and told me that I was working off the question of guilt and hate and that they were destructive emotions—I had to start working off of love—and that the United States government had used me and taken my precious idealism and used that to get me to go to Vietnam and kill Vietnamese, and I had seen that was wrong. And that now I had taken the correct political stance, but I had to deal with it emotionally as well. If I didn't change, I would become self-destructive. I had to see that it wasn't my fault. When the war would end and there would be a great victory, the victory would not only be theirs but would be mine as well. Unlike any other American, I would be able to join in their victory because I had seen the war from both sides. It was a transformation time for me. Unbelievable.

What do you mean by "transformation time"?

That's where my love for the Vietnamese comes from. Here were people who had never gone to college. Here were people who owned one suit. Here were people who were having the equivalent of a nuclear bomb dropped on them every single day. Here were people who could cry, because I was crying, who could reach out and be that much of a human being. What they truly and genuinely were concerned with was me. My God, this is unbelievable. So the question of loving and respecting the Vietnamese grew out of that.

Nixon was pulling out GIs and turning it into an air war. I knew what B 52s could do. There ain't no precision bombing. A worldwide effort stopped Agent Orange from being used in Vietnam by the United States. We just gave it to the Vietnamese, our surrogate, to keep dropping on the Vietnamese. We knew that 6 percent, or whatever it was, of the population, was being born deformed. The more the war became technological, the more the war became clean for America, the dirtier it became for the Vietnamese, the bigger blot it was on the United States.

I had to deal with the innocence of the Vietnamese. If I invade their country, then I have to have a reason. The reason is they're vicious, evil, rotten communists, right? They're out for worldwide destruction, and if I don't defeat them in Vietnam they'll be here; but if I went over there and slaughtered them, killed people, and bombed them, and they were never going to come to the United States, they become innocents. They didn't become equally wrong for living in their own country. You can't allow them to die. That became the imperative. We knew we were fighting for little kids being born deformed and we knew we were fighting against people who were bombing dikes.

I came back and I was an absolute maniac because the stress had been too much, despite the fact that I had gone through this little catharsis with the Vietnamese. I have just relived in my dreams every firefight in Vietnam. I've been bombed, seen bodies ripped apart, and been through the most intense two weeks in North Vietnam. Now I had come home and the war wasn't over!

[I] got back on New Year's Eve to New York. I'm getting up in the morning the next day, I think at three, to do CBS morning news with Walter Cronkite. I debated the head of the Conservative Party.

I would say, "Con Son Island. I met these people who were tortured." He would say, "Well, these aren't young Republicans on Con Son Island." I'd say, "Quite the contrary. Truong Dinh Dzu, who was number two in the last election, was arrested afterward, and he's there.

This woman from the POW families kept saying, "We want our relatives home." I said, "Well, if you expect them to come home before the war is over, then you're expecting a first-time event. We didn't let Germans go and Germans didn't let Americans go. POWs get released at the end of a war. If you think they're going to release pilots who then can come back and bomb them a month later, this is not going to happen. If you want them back, peace. There's no other alternative."

If I do say so, I smashed the guy. Afterward, he shook my hand and said, "Oh, you're a really good debater." I said, "Truth. It's not debate; it's truth."

Then I went on the road because we were building for the counterinaugural. So I went on a God knows how many states' tour. I would give five, six, seven speeches a day in building for the January 20 counterinaugural. I was just burned to a crisp.

The peace movement was alive and well. A million people went. We had 15,000 from VVAW. We met at the Arlington cemetery and where we had camped. We signed the People's Peace Treaty and another agreement, and then we joined the larger demonstration. This was probably our strongest point.

Before he won his second term in office, Nixon turned his attention to other matters of foreign policy. He opened dialogues with China and struck new deals with the Soviet Union; and he and Kissinger felt that they could rely on these new friends to pressure their North Vietnamese allies into signing a lopsided peace accord, which would favor the South Vietnamese government

For Nixon, Vietnam became more and more of a distraction that he wished to be rid of. After the Christmas bombings in 1972, he accelerated the peace process. An accord was finally signed on January 27, 1973, only a few days after the inauguration. This agreement was basically the same one that Nixon had rejected in October 1972; evidently, the earlier rejection had been calculated to ensure his reelection by prolonging the peace negotiations until after the voting,

In the months following the accord, POWs were released and the withdrawal of American troops was completed. The war was now in the hands of the United States' proxies in South Vietnam.

From this point on, the American press, and the public, virtually ignored Vietnam; but VVAW members who had been educating themselves knew that the war raged on, funded by the United States. Since many of them, like Barry Romo, had come to sympathize with North Vietnam, seeing the war as a struggle by the Vietnamese for independence, they remained committed to their anti-war crusade. For many in VVAW, however, the end of direct American involvement brought an end to activism.

Copies of Winter Soldiers can be purchased through Haymarket Books at www.haymarketbooks.org/books/859-winter-soldiers.

|

| The aftermath of the Christmas bombings in Hanoi, December 1972. |

|

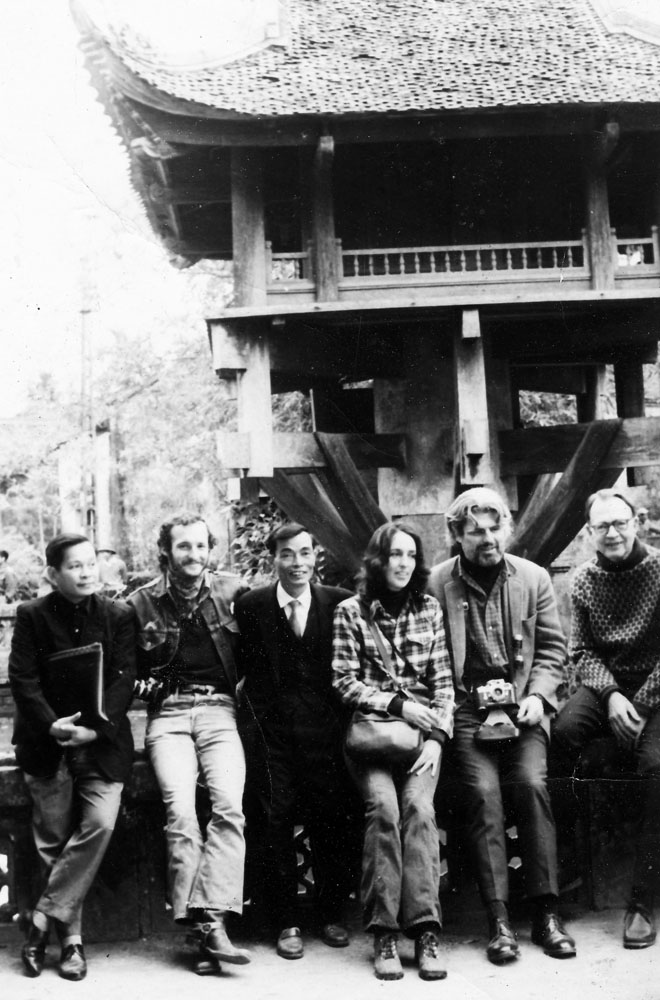

| Barry Romo, Joan Baez, and others at the Symbol for Freedom in Vietnam, December 1972. |

|

| Bombing site near the Cuban Embasy in Hanoi, December 1972. |

|

| Bombed Bach Mai hospital in Hanoi, December 1972. |