Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB)

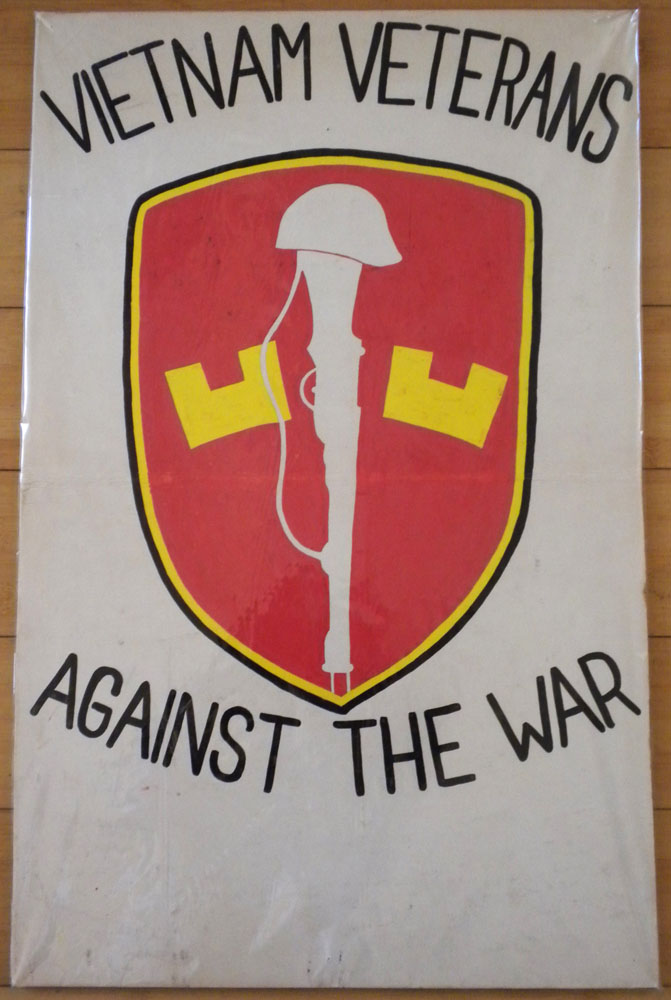

Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=4113

Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v52n2.pdf (36.5 MB) |

I left my 3rd Marine Battalion tank company at Con Thien at the DMZ in January of 1968 and less than 10 days later, I was walking the streets of San Francisco as a civilian. (Drunk, I missed my scheduled flight out of the country, certain that I would die that night in a rocket attack on DaNang airfield.) I didn't know the term then, but I am sure that I experienced culture shock. Not only because I was in the heart of the Peace and Love Hippie movement soon after the "Summer of Love," but also because there was no sense that there was a war going on. The red mud of the "Hill of Angels" was still oozing from my pores and my buddies were still ducking (and sometimes dying from) NVA artillery shells there, but here in this All-American city, life was being lived "normally."

I was heading to my parent's home in New England but stopped first to visit friends of theirs who lived in Alameda, just across the bay to the east of the city, who graciously welcomed me into their home. I was "free" from the war, or so I thought and was now just a normal person like everyone else. So when my parents' friends' daughter, home from college for the holidays, who at the urging of her mother had written me a letter or two while I was in country, took me into the city to sight-see, I proposed to her after a few hours together. She had the good sense, thankfully, to gently refuse—thus sparing her and I many years of torment that we would have certainly faced had she accepted. After a few more awkward days in Alameda, I caught standby flights and eventually made it back home.

Although not as glamorous or hip as San Francisco, my small New England former industrial city did share the same seeming amnesia—there just wasn't any sense of the country being at war—even though the count of local boys, including high school friends, who had died in Vietnam was growing. (Despite editors and glib-mouthed politicians' fondness for the term, no one "gives" their life for their country. It is torn from them by jagged molten metal, the silent snap of a bullet, or obliterated in a microsecond blast of high explosive.) At least one person, however, had a certain awareness of, if not the war, then one of the warriors. Because I couldn't tolerate my parents' daily routine I moved into an apartment and soon after, started receiving telephone calls from an unknown man whose age I couldn't decipher. When I'd answer he'd say things like, "So, you think you're a hero, huh?" or, "Did you kill a lot of kids?" I told him that if he had something to say to me, then he should do it to my face. After several weeks the calls stopped. Whatever euphoria I felt at having survived and making it home was soon replaced by a sense of unease and dislocation, exacerbated by the news of the ferocity of the TET offensive that lit up the TV screen every evening, as I imagined my friends struggling to survive in Hue, Khe Sanh and the DMZ.

I was smoking a lot of pot to try to keep at bay the conflicting surging emotions straining just below my consciousness, and with varying success. I crashed the demo sports car that the owner of the dealership I had gotten a job with had generously given me, and treated women like they were Vietnamese whores. I muddled through a year or so of living as if in a confusing fog, and when a second cousin close to my age told me that he and a friend were driving to California to go to college there, but first were stopping at a music festival in New York, I gave notice at work and said goodbye to my family with no hesitation.

Woodstock was like falling down the rabbit hole and going through the looking glass all at the same time. After the rigid discipline of the Marine Corps, to experience people taking care of one another just because it was the right thing to do, was truly, "mind-blowing." And after literally getting run out of Long Beach by the cops—"we don't want your kind here"—we ended up in San Francisco. My cousin and his friend returned to New England shortly thereafter but I stayed on, and eventually migrated up to Sonoma County, where I enrolled in Santa Rosa Junior College. It didn't take long for me to meet other veterans—we were as recognizable to one another as if we were wearing a scarlet "V" on our chests. We naturally gravitated together and formed an impromptu "rap group" years before it became an accepted form of therapy for veterans. We formed a chapter of VVAW as well as the IPC (Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda's Indochina Peace Campaign) and together with anti-war students and sympathetic faculty, took control of the student government, organizing teach-ins and demonstrations. In one march through downtown Santa Rosa after the 1972 Christmas bombings of Hanoi, a manager at a bank that I tried to leaflet in, became irate at such an expression of First Amendment rights. When I told her that I had fought and been wounded in Vietnam, her forever indelible response was, "Too bad you didn't die there!"

I will forgo detailing the decades of difficulty of coming to grips with my experience in the war—it is probably no worse or better than that of thousands of my brothers and sisters. Perhaps it is best summed up by this quote from the Netflix series, The Liberator. Just substitute "Vietnam" for "Anzio."

"Why am I alive to write to you when so many are gone? I know I should feel lucky, but instead I feel my soul starting to fray. I know I can hang on, thinking of you helps. But for the rest of my life, if ever I go silent or weep for no reason or seem to leave you when you're right beside me—remember one word and you'll know where I am—Anzio."

Fred Samia is a freelance journalist who has worked in the Middle East. He served in Vietnam with A Co, 3rd Tanks, 3rd Mar Div, 1967-68; his eight decorations include the Purple Heart. He has been a member of VVAW since 1970.

|