Download PDF of this full issue: v52n1.pdf (24.3 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v52n1.pdf (24.3 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=4086

Download PDF of this full issue: v52n1.pdf (24.3 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v52n1.pdf (24.3 MB) |

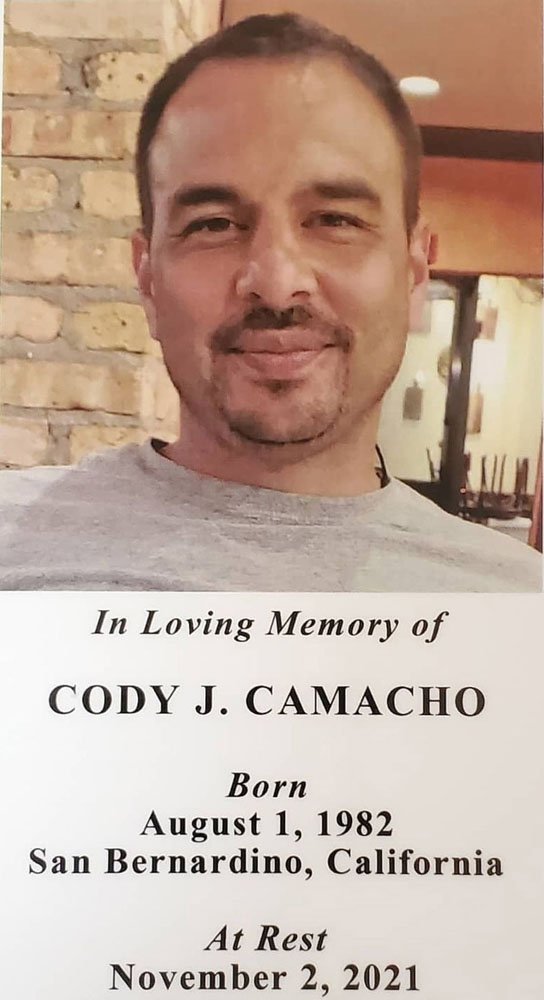

I wanted to write an article for The Veteran about my son, Cody Camacho, to let those who knew him know about his death—and issues with the care (or lack of it) for PTSD he received from the Veterans Administration—in particular the "off label" use of antipsychotics that have serious side effects including increased anxiety and suicidal thinking. We feel these drugs contributed to his suicide on November 2, 2021, at the age of 39.

Cody joined the Army straight out of high school in 2000, was trained as a communications specialist, spent three years in Germany, then deployed to Iraq at the beginning of the invasion in 2003, what was to be his last year of active duty. For over six months of the year, Cody was in Iraq, he was based at the Abu Ghraib prison. He was there during the time that the famous torture pictures were taken, although like most, Cody lived outside on the grounds. The buildings were not really used, except by torturers. Cody left Iraq in March 2004, around the time that the Abu Ghraib torture hit the news. In addition, to the experiences commonly associated with PTSD, Cody had the additional problems I have noticed in others who were based at correctional facilities—and in his case, a great shame at being connected to a notorious prison where documented, widely publicized acts of torture took place. He did not want to walk the streets of Germany in his uniform.

He called me from Germany to tell me he was coming stateside to visit, and that he wanted to talk to the media. Even before the war started, I joined Military Families Speak Out and had been pretty active. Cody did not agree with the war either. I went to Germany two weeks before he deployed, and tried to help him find a way not to go. He told me: "They are going to send us into Iraq and do horrible things to the people there, and we will be blamed for it." Now, he had things that he wanted Americans to know—that he thought that he and thousands of other soldiers were kept in Iraq because the contractors like Halliburton were making so much money. No soldiers deployed, no more money. Since Cody was still on active duty, this was a big decision. He was among the first large wave of Army soldiers to leave Iraq; we did not know what the consequences could be. But two radio shows were set up, Democracy Now and Counterpoint. I searched these old shows out, wanting to hear his voice in my grief. You can listen to young Cody fresh out of Iraq on Democracy Now—March 19, 2004, exactly one year after the start of the war.

If you met Cody, it would likely have been at Camp Casey, at an event in DC, or a stop on the Bring Them Home Now tour. Before he left for Iraq, he was married to a German—this was not to last, she was unprepared for what lay in store when he returned, and when the marriage broke down, he came back to the states and contributed to anti-war activities from Fall 2004 until January 2006 when he returned to Germany. He met many Vietnam vets during his travels who were very important to him, who helped him as he first came to terms with the reality of war and PTSD. You may not have heard from Cody for years, but trust me, he thought of you often. He was grateful for the help he received from those who had been down the same ugly road. Truth be told, when he first went to Camp Casey, he was in the absolute depths of PTSD, was not sure what was going on, but had the irrational idea that a ticket from Chicago to Crawford, TX would get him closer to Ft. Bliss in El Paso where a friend was stationed—he was desperate to be with those he deployed with, thinking no one else would understand. He never made it to Ft. Bliss, but the many VVAW members who passed through Crawford listened to him and did understand, and he never forgot who helped him take that first step forward.

In 2006, Cody decided to try to reunite with his wife in Germany. He had not been able to adjust here; he could not do all the steps it took to get a job, even though he had worked since he was twelve. He had no money and was tired of drifting. Once in Germany, he went back to the Army as a civilian worker, for many years he worked various human resources jobs for the Army at different bases in Germany, with a close to two-year stretch in Kuwait.

The relationship with his German wife did not last, and while he was in Kuwait, he reconnected with his childhood sweetheart from day camp, my beloved daughter-in-law Chyla, the mother of his daughters Desiree and Calina, who all miss him so much. He returned to the US and worked as the administrator for Army reserve units in Illinois, with a three-year stint in K-Town. In total, Cody spent about 16 years with the Army. It was not so much love for the Army as that it helped him function, something he did not find in civilian settings—he was always around people who would understand. Upon returning from Germany in 2014, with his second daughter born shortly afterward, he and Chyla bought a home in Des Plaines, IL. He was so proud he was able to do this. He also began counseling through the VA in earnest. He had flirted with the VA early on but was reluctant due to the bureaucracy and their fondness for drugs. He also did not want the paperwork on him to exist, he did not want the stigma of being a disturbed veteran. This bothered him.

He decided it was time to step away from the Army. He looked for another federal job and was hired by FEMA with disabled veteran status. He thought he would be helping people in the field and went to their training camp, but found himself instead in a stressful office setting with the kind of internal politics that you find in government jobs—he was miserable in that job but felt he needed to keep it. Without going into too much detail, in Cody's words, they hired him as a disabled vet then fired him for his disability. A complaint by another employee that Cody made her feel threatened due to some things on his Facebook page she had seen—which I would call unwise and juvenile but hardly threatening—led to close to two years on paid administrative leave, then termination after finally getting a required psychiatric evaluation by a contract psychiatrist who met with him for one hour and ruled him "unable to be rehabilitated." His intended reintegration with a civilian job had not turned out well.

When this first happened, I was so worried. It was such a blow to Cody, he was so embarrassed and hurt to be considered a disturbed vet who might be threatening, to be investigated in this manner. But instead, Cody blossomed. He was so depressed going into that job every day, and it was like a weight lifted. He began going to various group sessions at the Hines VA two to three days a week, joined the Des Plaines American Legion, and through that became involved with other community activities. For the few years before his death, Cody was doing well and spending most of his time in service to others and caring for his family. He became active with a back-to-work veterans program in Des Plaines. He revived the American Legion chapter, mainly made up of veterans of Korea and Vietnam who were much older. He helped many of them deal with their own PTSD, to get benefits they had never even applied for. Despite the differences in political opinions, Cody became very important to them, serving as Vice Commander at the time of his death. He was working with others to try to get a veterans service office connected with the City of Des Plaines

I last saw Cody in August 2021. We had not seen each other since 2019. Cody built a nice patio during the pandemic—his yard borders on a beautiful park, right next to a naturalized pond with geese and ducks; it is such a peaceful place. We sat out there together and talked, at night with a fire. When I think of him now that's where we are. He was doing so well. Usually, when I visited, there would be at least one PTSD blow-up; this time there were none.

About a month later, Cody began having symptoms, anxiety, and a sense of being threatened by things that were not really threats. In conversations, he would start with something or someone that was bothering him, which at first seemed normal, then go off into detailed descriptions of how this was a threat to him or his family. He was worried that rather than just PTSD, he had some more serious mental illness and said he could not control his thoughts. He told his therapist at Hines he was not sure he knew what was real and what was not. This had happened before, I told him that if he wasn't in touch with reality he would not know it, and would not be able to recount his symptoms to me.

The types of things that personnel at the VA write in charts or say to veterans in their care, like the notorious schizoid-effective disorder diagnosis, play into this fear that many have of other mental illnesses. In all truth, this began at a time when the girls were back in class after online schooling for over a year, and Chyla who has her own business doing hair and make-up for weddings was working more. And Cody wasn't working, he now had too much time on his hands and too much time to think. I encouraged him to find things to do and to make sure to talk to his therapist to straighten out his thinking.

The crisis began in earnest in mid-September, when a friend from the Legion, a Vietnam vet who is a retired cop and has much experience dealing with both the VA and mental health crises, took him to the Hines VA emergency room because of his extreme anxiety and things he was saying that did not make sense. This friend expected them to admit Cody, but instead, he reports that the visit took only about half an hour. Cody said that he was given a shot of aripiprazole, an antipsychotic commonly known by its brand name, Abilify. He then was released to go home.

This appears to be the first time he was given antipsychotics. In later conversations, he seemed to be doing better, although still having symptoms. The last time I talked to him was a little over a week before his death. He had been out with a good friend with whom he had planned to open a business before the pandemic, and talked of working with this friend in a restaurant he managed, and how he was going to try to get his oldest daughter Desi in a fancy arts high school in Chicago. He sounded better, and he was doing the things he needed to do to manage his symptoms. He also mentioned that his psychiatrist at the VA changed his medication. After his death, I learned that this was risperidone, a more powerful antipsychotic with a black box warning about suicidal thinking. I told Cody I did not think he should be taking antipsychotics—he had always refused them before. He just said that he was not going to take them very long.

On November 1, Cody bought his children McDonald's for dinner, called his wife at work and told her he fed them, then left the house never to return. At some point, he took a gun and went to a hotel room.

I left for Chicago after learning of his death the next day. Cody's funeral was huge and uplifting, and befitting the kind of person he was, all kinds of people were there. It was sad because he was not there to see how loved he was. During the week before and after the funeral, his house was full of people, many good friends who had known him for 20 or 30 years, many who reported talking to him during the last week of his life and how strange his behavior was. He told people he was marked, that people were after him, and other things that made no sense. During the time that he was taking this new antipsychotic, risperidone—seven pills, we found the bottle and counted—his behavior changed and then we lost him for good. Cody had never been suicidal, he was a resilient person with strong ties to his family and many other people. We believe that the risperidone contributed greatly to this outcome.

Two days after the funeral, Chyla and I went to Hines to talk to his therapist. I just kept having this idea, as what happened with Cody during that last week became clear to us, that I would like to tell his therapist what we think happened. When I talked with him on the phone the night before, the first thing he said was "I was so shocked. Cody was doing so well." I believe that he learned of Cody's death because the VA psychologist he had referred Cody to for more advanced cognitive therapy—which is what he really needed—called Chyla the day after the funeral when he could not reach Cody to set up an appointment. By then it was too late. When we got to his office, there was a woman there, the person in charge of the Hines suicide prevention program, someone who did not know Cody at all, and I am not sure why she was there other than to give us brochures.

She started off controlling the conversation, but mostly Chyla and I expressed our belief that the antipsychotics Cody was prescribed played a large part in his drastic change in behavior and his death, and that we did not believe he was suicidal at any time before beginning these drugs. As we were leaving, the woman said something like "You can never know what is in someone else's mind" and "He planned this. You just have to accept it." It was clear to me that she considered this over, and that we should just move on with our lives. I find it quite disturbing that the person who is charged with suicide prevention at Hines did not see it as important to look into why this happened, especially since he was under their care and had recently been prescribed drugs by them. It was as if he was just another veteran, and veterans commit suicide, end of story.

We will never really understand what happened to Cody. It all happened so fast. It was as if he was deep in the midst of activity and life then suddenly was gone. Right now, I am exploring ways to hold the Veterans Administration accountable, particularly their use of these "off-label" drugs with serious side effects, rather than the real help that veterans need in times of crisis. This is not a new issue, there are countless congressional hearings.

It is hard to know where to start. I am researching, writing letters to key congress people, and above all looking for other cases either of veteran suicide while under the care of the VA, or experience with antipsychotic drugs used to treat PTSD. One thing that has become clear so far is that once a veteran dies by suicide they become nameless and faceless statistics. Of the many who die each day, it is difficult to find even news reports with much detail or even a name. What is needed is not just the general statistics, but the details of the care provided. People can look at Cody's face and know what happened to him. Please keep this in mind. If you know of other cases that might be helpful, or want to share your own experience, or just want to write, you can reach me at ForCody1982@gmail.com.

Jeri L. Reed lives in Oklahoma and teaches history at Oklahoma City Community College. She raised four sons in Chicago?two of them Iraq War veterans.

|

| Cody Camacho, Brooklyn, New York - Bring Them Home Now Tour, 2005. |

|

| Chyla, Cody, Desiree, and Calina - Christmas 2020. |

|