Download PDF of this full issue: v51n2.pdf (30.7 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v51n2.pdf (30.7 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=4027

Download PDF of this full issue: v51n2.pdf (30.7 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v51n2.pdf (30.7 MB) |

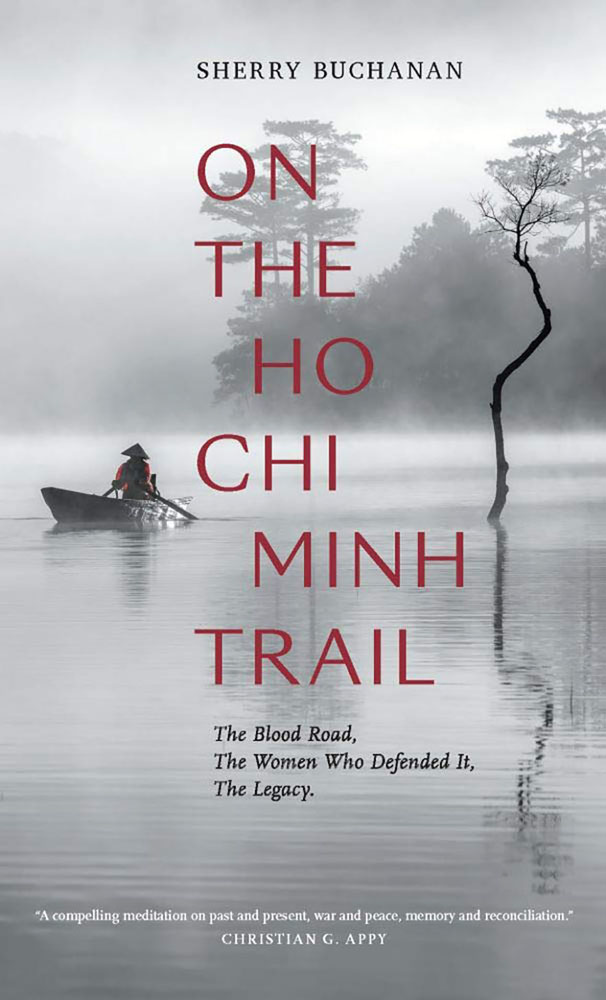

On The Ho Chi Minh Trail: The Blood Road, The Women Who Defended It, The Legacy

by Sherry Buchanan

(Asia Ink, 2021)

Between 1965 and 1975 the United States dropped some 7.5 million tons of bombs on Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, more than double the weight of bombs dropped on Europe and Asia during the entire Second World War. While there were multiple and changing objectives to the bombing, a major one was the disruption of the flow of men and materiel to the south. Consequently, much of that fury was directed at what the Vietnamese called the Trường Sơn Road and the United States named the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

The Trường Sơn Road /Ho Chi Minh Trail threaded through the Trường Sơn Mountains, known in the West as the Annamite Range, that runs roughly north-south through almost the entire length of Vietnam. The Trail was not a paved highway but a track that shifted, changed shape, collapsed, and regenerated over time and in response to changing circumstances. It eluded all attempts to destroy it, though it became an obsession on the part of the United States military to do so. That the military failed is due in large part to the efforts of thousands of women.

|

These women play a central role in Sherry Buchanan's On the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which documents her search for those who had lived under those bombs. What drew her to the Trail—oddly, for a story that is so much about bombing runs and tonnage and death—were drawings of the landscape and daily life made by both military and civilian artists. Her curiosity was driven by the large number of women who populated these drawings.

Buchanan started in Hanoi in the winter of 2014 and traveled by car with two companions, stopping at key sites and meeting with those who had memories of living beneath the bombs. She began, she said, by looking for "the other side of the war," the humanity of those the United States had so fiercely sought to destroy, and she found "another side, a gendered one."

She found the remains of a trail on which some stations provided food, shelter, fuel, and security, a complex communications network, and anti-aircraft units all hidden in natural caves, man-made tunnels, and under jungle canopies. She also found why destroying the Trail had been such a futile endeavor:

The women in the war drawings "protected" all this. They prepared food, repaired roads, transported ammunition and weapons between stations, drove the trucks, decommissioned live bombs, joined anti-aircraft defense units, nursed the wounded, and buried the dead.

She meets as many of these women as she can, starting with the actress Kim Chi who had hiked 600 miles on the Trường Sơn trails after having talked her way into the war. She finds Nguyen Thi Kim Hue who had been given the highest military award by Ho Chi Minh himself for her work on one of the most dangerous stretches of the Trail. After her village was destroyed, Hoang Thi Mai trained first as a sniper and then as a nurse. Ngo Thi Thuyen who, at 92 pounds carried two ammunition boxes with a combined weight of 216 pounds, tells her that the reason Vietnam won was that "We were home, they were far away from home."

She finds the artists, too. In Hanoi, she visits Tran Huy Oanh who has a collection of portraits and lyrical landscapes, surprisingly large given the grueling conditions under which the drawings were preserved. She speaks with another artist, one who said he had seen the souls of five girls killed on the Trail. Two of Nguyen Van Hoang's watercolors, both called "Crossing the River" and dated in 1971 and 1972, are quick sketches that capture the strength of the landscape and the movement of human figures through it.

Her fascination with the Trường Sơn Mountains is infectious. She had been captivated by the beauty she had seen in the landscape drawings and, as the journey progressed, hoped for the clouds to break so she could see the mountains themselves. When that happens for the first time, she recognizes that "the landscape depicted in the drawings expressed more than a geographical place, it reflected a state of mind, 'the calm mind needed to survive such a cruel war.'" This "calm mind" (the quote in her sentence is not attributed) seems to be a clue to the dignity and courage she finds in the artists and veterans she meets.

This is a beautiful book. Published in London and printed in Italy, it contains maps for each section and color reproductions of art, as well as photographs of women and landscapes taken by the author. It is also a confusing book. In her Preface, Buchanan says she made the journey to collect stories "from both sides of the front line." She wanted their testimonies "to confound the abstraction of war that makes it acceptable to those of us who live in more peaceful places." That alone makes a profound and almost unique contribution to the all-too-limited awareness in the United States of the stories of individual Vietnamese people. She does not let that stand on its own, though. Threaded throughout is a personal quest that competes for attention.

The welcome that Americans receive in Vietnam, usually called "forgiveness" (although it is unclear if the words are understood in the same way in both cultures) is so mysterious and compelling that many Americans, Buchanan seems to be among these, look to Vietnamese for answers. In all her interviews, for example, Buchanan asks probing questions, such as whether the person she is visiting was afraid or felt hatred or thinks the United States should pay reparations. By the time she reaches the Epilogue she has decided that she went on the Trail because she "cared that a government that claims to bring democracy and human rights to the world—and preaches it to others—was partly responsible for two million civilian war dead in Vietnam and hundreds of thousands more in Laos and Cambodia." She decides the United States has not done enough, that colonialism should be confronted, and the civilian deaths we are responsible for should be commemorated. By the end, the journey has become personal, a lament for the damage war inflicts, for how it affected her own family, and how she has moved on. It is difficult not to feel that once again the stories of Vietnamese have been subsumed into the stories of Americans.

This observation does not undermine the contribution her book makes, however. Buchanan's journey may have had a confusion of both motivation and outcome but she made the journey. She set out to find stories, stories that are utterly foreign to most Americans. She found them and she told them. Coming to terms with those stories and others like them is a responsibility that lies not with her alone, but with all of us. Current events continue to demonstrate the urgency of that task.

Susan R. Dixon is the author of Seeking Quan Am: A Dual Memoir of War and Vietnam. She may be found at www.susanrdixon.com and www.seekingquanam.com