|

VVAW and the Literature of WarBy Elise LemireI teach a course at a public liberal arts college on "The Literature of War." In the first half of the course, we read novels by Rebecca West, Ernest Hemingway, Kurt Vonnegut, and Tim O'Brien, in which men go to war to fulfill their country's masculine ideal only to suffer the consequences. In West's Return of the Soldier (1918), three women conspire to jog the memory of a shell-shocked Chris Baldry so he can return to WWI's western front. For them, his likely death in battle is preferable to staying home, where Chris would be what one of them describes in homophobic and ableist terms as "forever queer and small and like a dwarf." In O'Brien's The Things They Carried (1990), Tim, the narrator the author names after himself, is presented with an opportunity to escape to Canada after he is drafted in 1968 but cannot imagine crossing the border. "I would kill and maybe die," he explains, "because I was embarrassed not to." In Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms (1929), Lieutenant Frederic Henry is distressed to hear that his friends want to enter his name for a medal when the circumstances of his serious leg injury do not fulfill his ideal of masculine wartime valor. He was, he protests, eating spaghetti in a bunker with several other men when they were hit by a mortar. Each of these narratives is riddled with memory lapses, moments of disassociation, and other marks of trauma. Readers are not simply told about war's horrors, they are shown the effects of what Dr. Jonathan Shay calls "moral injury." At this point in the semester, my students are convinced that Slaughterhouse-Five, which recounts the American firebombing of Dresden at the end of WWII, provides the last word on war. "So it goes," the novel's famous refrain, repeats a grueling 106 times. In the second half of the course, I ask students to read the Vietnam war memoir Born on the Fourth of July (1976). Ron, the narrating self-author Ron Kovic crafts, compares his birth with the nation's, initially believing that both he and it are beacons of freedom and democracy. In Basic Training, however, the values of the patriotic citizenry and the Catholic church square off in his head with the homophobic and misogynist orders he receives. Kovic represents Ron's internal confusion with run-on sentences, italics, and capitalization: "Oh hail Mary full of grace the Lord is motherfucking cocksuckers! Oh Our Father KILL! KILL! KILL! KILL! Who are in COMMIES JAPS AND DINKS hallowed be IF YOU WANT TO BE MARINES…." and so on for several pages. Ron becomes convinced he must kill Asian people or become a "lady" and a "maggot." And thus, in Vietnam, after mistakenly firing upon and killing civilians and their children, he tries to redeem himself by playing the hero in a firefight that leaves him paralyzed from the chest down and, later, furious with the Veterans Administration for its inhumane treatment of wounded American soldiers. Deeply shaken by what Ron endures, my students rejoice when his journey does not end there. Ron takes back the agency the military and the VA denied him by joining Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW), an organization that gave him a powerful voice on the national stage. For the first time in our course, my students are hopeful that individual Americans can affect meaningful change.

To make clear that Ron Kovic's experience was not unique, I end the course by asking students to read interviews conducted by the Lexington (MA) Oral History Project (LOHP) with those members of VVAW who participated in Operation POW.

In what follows, I have woven together with a minimum amount of commentary three lightly edited accounts of Operation POW culled from the LOHP archive as well as from an interview I conducted myself. I offer them here with thanks from my students for whom "so it goes" is not an acceptable answer to the problem of war. Chris Gregory's father was a moderate-to-conservative Republican who envisioned a future for his son as a priest or as part of the family business. "When I was seventeen, I decided that it would be a good thing to leave," Chris explains. He enlisted shortly after his next birthday. "It was really the only acceptable way to get out of the New Jersey town I was living in, the situation I was in." It was 1964 and, for Americans at least, "Vietnam was not on anybody's map." The Air Force trained Chris to be a medic. For almost two years, he worked in hospitals around the country, his longest stint being in an intensive care unit on a base in Florida's Fort Walton Beach. When Chris asked the sergeant running the ward why he had not been promoted for what he knew to be good work, the sergeant explained that it was simply a case of someone being ahead of him in the queue. To make it up to Chris, the sergeant proposed sending him to train to be an Air Evacuation Medic, which paid more. "I would go to Alaska, meet planeloads of wounded soldiers and distribute them around the East Coast," Chris explains of his new job. After the Tet Offensive, Chris started flying to Vietnam where he would pick up the wounded in plane loads of two hundred men at a time and take them to whatever stateside hospitals had room. "We got people who were quite badly hurt and quite recently hurt, who had not been in a hospital, who had only been triaged. They still had on battle fatigues and were very recently wounded, but there was no place for them so we would take them somewhere. Japan or the Philippines were the closest places." Many of the wounded were dealing with severe emotional trauma as well as, or as a result of, their grievous physical injuries. "They had just realized how badly they were hurt," Chris notes. "A lot of them wanted to get out of the country so badly, they would conceal the seriousness of their injuries. They would actually be bleeding and hemorrhaging and not say anything, because they thought you'd take them back. So, you'd end up having big, big problems when you got off the ground, because there was no physician. Even if there was a physician, you don't have an operating room or anything. You can do what you can do, but it's not the same as a hospital. It was very, very…," here his voice trails off. "It's very hard to describe because you're so passive. One is so passive at this time. This is happening to you and you can't affect it in any way; your imagination doesn't work as well as it does when you're influencing something." Chris describes feeling bad that he did not have time to be as sympathetic or gentle as he would have liked. "I still think about some of the injuries I saw. People were very badly burned or very badly wounded, losing more than two limbs and so on. You wonder, 'Wow, how could I not have related to that person in a more gentle way?' But at that time, it wasn't possible for me." He remembers reading Susan Sontag's article "Trip to Hanoi: Notes on the Enemy Camp" in the December 1968 issue of Esquire. ("I came back from Hanoi considerably chastened," Sontag writes. "It would be a mistake to underestimate the amount of diffuse yearning for radical change pulsing through this society.") But he also remembers putting aside Sontag's compelling case for Vietnam's independence and getting back to work.

"Whether the war was right or wrong didn't occur to me." "My life wasn't really going anywhere," is how Lenny Rotman puts it when describing the spring of 1968. He had graduated from a public high school in Boston and was working as a salesman in a shoe store on Boston's tony Newbury Street without paying too much attention to what was going on in the wider world. Unbeknownst to Lenny, Robert Talmanson was receiving sanctuary at a church visible from the store where Lenny worked. Arlington Street Church had decided to open its doors to the twenty-one-year-old Massachusetts resident after the US Supreme Court refused to allow him to appeal his conviction for burning his draft card two years earlier. On May 22, after Talmanson had been in the church for three days, US marshals swept in. When Talmanson went limp in peaceable protest of his arrest, the marshals proceeded to drag him outside only to confront a growing crowd of protestors who stood between the church and the marshals' vehicles with their arms locked. After a forty-five-minute standoff, during which the protestors sang patriotic and civil rights songs, over thirty Boston police officers showed up to escort the marshals. "I watched the police charge through groups of people who were sitting there passive and then banging people up against cars and clubbing them," Lenny recalls. "Blood was everywhere." Not long thereafter, Lenny got drafted. Two of his friends who also got drafted found ways to get out of serving. One, who Lenny describes as an "outstanding athlete," obtained a doctor's note to the effect that he had sustained some sports injuries, even though he was still active. Another "ate a dozen eggs or something" and thereby elevated his blood pressure. For Lenny, however, the draft was an opportunity, not merely to surpass a local football hero, but to see for himself what was at stake in the showdown at Arlington Street Church.

"I was home for quite a while from Vietnam and out of the military before I could admit that while I didn't really want to go, a big part of me really was interested in having that experience." That fall, Fred Davis was on his way to Vietnam with the charge "to conserve the fighting force." Fred had completed medical school on the Berry Plan, a federal program that allowed medical students to delay induction until after part or all of their specialty training in exchange for establishing a firm date for the commencement of their tours of duty. He had completed part of his training as a surgeon in Boston, Massachusetts, and his wife was pregnant with their second child when he was ordered to begin his one-year tour overseas. Fred recalls that there was supposed to be a two- or three-day orientation once he arrived in-country, but a doctor got killed and Fred was needed to replace him. This and the fact that all of the dispensaries were named after doctors who had also been killed made it immediately clear he would be in danger. He started counting down the days. Fred spent two months of his tour assigned to a small emergency room near a route traveled daily by a United States convoy. The military could easily have flown in supplies but American officials were determined to show they could establish a land route. "We'd have lunch and then wait for the casualties to come in," Fred recalls of the daily ambushes. Those who avoided physical injury suffered from acute stress. Fred remembers sedating them with Thorazine for 24 to 78 hours. It was a way to provide them with rest and "a little amnesia," as he puts it. Another persistent danger was boredom. "There was an open area with a big drain pipe in the middle and a tent," he explains of the bathing area. "A guy decided to role a smoke grenade into the tent and then have a big smoke bomb in the middle of the shower. Well, he rolled a regular grenade down there instead. Fortunately, it went down the pipe before it went off and so it just blew a big hole in the roof." As opposed to five or ten fatalities, there were, he recalls, a few concussions and ruptured eardrums. Other victims of boredom were not so lucky. Fred recalls that nearby American troops were charged with ensuring that Vietnamese guerrilla fighters did not swim under the bridge they were guarding and plant dynamite charges. "One of the ways they would counteract them was taking grenades, pulling the pin, and dropping the grenades into the water. Well, that got boring and so guys would pull the pin and see how long they could hold the grenade before they would drop it." The results were catastrophic. "In would come a kid without his arm," Fred remembers, sighing. "Things like this happened over and over." What Fred most remembers, however, was the extreme youth of the American troops. When he asked what he could get for the wounded at the nearby PX, the request was frequently for comic books. "I remember thinking that these are really little kids here. Here they are in the middle of this war and what they do for entertainment or relaxation is read comic books. I hadn't read one of these comic books for fifteen years." Fred was twenty-eight. While he had arrived in Vietnam "more of a hawk," he quickly learned that the war was not only costly, it was "pointless." The Tet Offensive clarified that none of the Vietnamese wanted the Americans there, even those Vietnamese ostensibly working alongside the Americans. "The Vietnamese cook's daughter was in the dispensary for days with pneumonia," Fred remembers. "She was getting better but was far from okay when the cook insisted on taking her home. We should have realized what was going on," he later recalls. That night they were attacked and the base was overrun. "She knew that was the night." When the mortars started coming in, Fred ran to the nearest bunker and discovered that the other Vietnamese working in the compound were already there.

They knew too. By September of 1969, Lenny was in Vietnam with the MOS 11 Bravo. ("That's the guy who carries the M16 humping in the boonies" or, in civilian terms, one of the soldiers carrying out search-and-destroy missions.) Three months later, Lenny was called out of the jungle for a family emergency. Back in the States, he ended up in the hospital for a week with a lingering infection from where some leeches had attached to his leg. There had been no way to have his leg treated properly out in the field other than to swap cigarettes for penicillin, so the cellulitis had spread. The doctor who treated him noted that if he had not been called home, Lenny could have lost his leg. An increasingly difficult family situation got Lenny a Compassionate Reassignment, and he spent the rest of his time in the military as a clerk at Fort Devens, which by the spring of 1970 was a hotbed of GI resistance. "That's when I started my anti-war GI work."

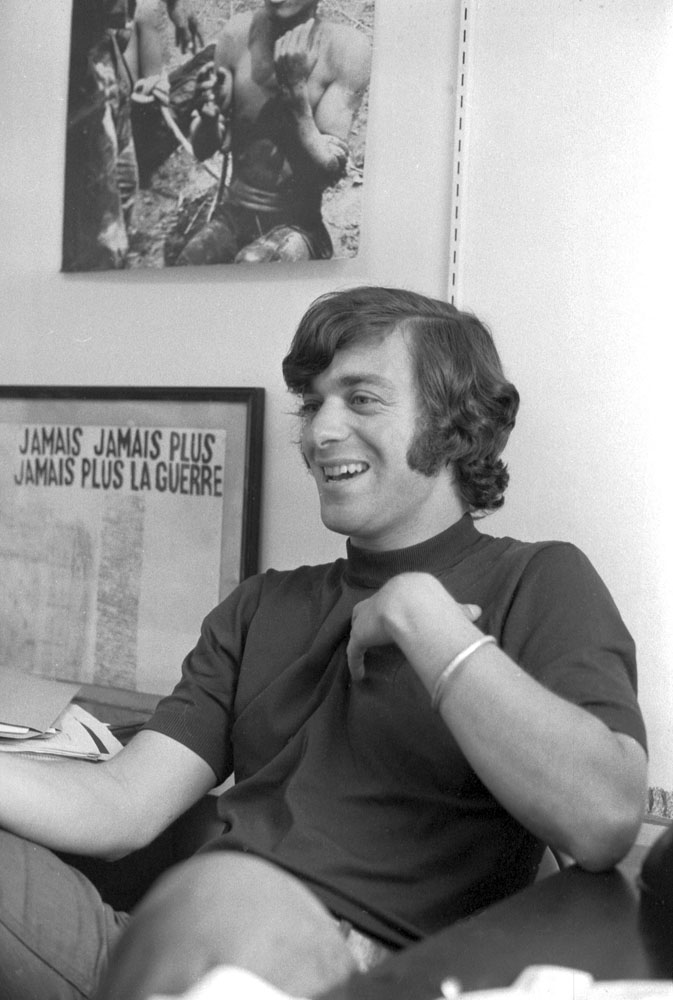

First, Lenny worked on The Morning Report, an underground newspaper. ("For those of you who realize that the aims of the military are wrong," the first issue, published in May of 1970, proclaimed, "we want to help you resist.") Then he started helping the Legal In-Service Project (LISP), a group of veterans counseling people in the service about how to get conscientious objector status. LISP's volunteers were forced to meet with GIs in the woods outside of the base. Later they were able to use a nearby anti-war bookstore. Chris remembers feeling "sort of numb" when he got out of the service in April of 1968 and enrolled as a twenty-two-year-old freshman in a program for veterans at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. Neither his parents nor anyone else had asked him about his experience in the service. And while he was pleased to be free of the military's rules, he was not free of the war. The television reported nightly on the increasing number of American dead. Not having anything in common with the sheltered eighteen-year-olds in his classes, Chris found himself alone with his memories about moving among so many wounded soldiers without the time or the emotional strength to address anything but their physical needs. It became impossible to talk to people who would not have been able to understand. "I went on one silence," as he calls it, "for two weeks." Recalling the camaraderie of the military, Chris found his way to Fort Devens at the same time as Lenny and other resisters were ramping up their efforts. "We had a shared experience, a shared analysis, and a shared discomfort with our participation," he later told the Boston Globe of the men he met there. Chris decided to work alongside Lenny and the others at LISP. One day, Jerry Grossman, the Boston businessman and founder of Massachusetts Political Action for Peace (MassPAX) who had dreamed up the Moratorium to End the War and who had helped LISP get a newsletter into wealthy donors' hands, approached them about having lunch with a former Naval lieutenant named John Kerry, now working as a spokesman for Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Chris recalls saying yes because it would be a free lunch. But he also recalls that he, Lenny, and the others very much liked what Kerry was proposing. "We want to put together a chapter here," he recalls Kerry saying. "We have a thing in New York. We've been working on it a couple of years. We had one demonstration," Chris also remembers Kerry explaining about Operation RAW during which VVAW members marched from Morristown, New Jersey, to Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. "We offer some services. We have rap groups, where these people can talk about their experiences. We put together a pressure group, a method of pressuring the VA into giving better services. Some of these guys have readjustment problems. We help them deal with them, but basically it's a political effort." And with that, the New England chapter of VVAW was born. A photograph of Lenny reveals a portion of the two rooms MassPAX gave the new VVAW chapter at 67 Winthrop Street in Cambridge, not far from Harvard Square (page 18). Lenny is seated next to a framed poster whose title "Jamais. Jamais Plus. Jamais Plus La Guerre" indicates it is a transcription of Pope Paul VI's address to the United Nations on October 4, 1965, which he gave in French, the traditional language of western diplomacy. ("Never. Never again. Never again war.") Above Lenny, on the wall, is an enlarged version of a 1962 photograph taken by British photojournalist Larry Burrows for Life Magazine that depicts a South Vietnamese soldier brutally interrogating what Americans would call "a Viet Cong suspect." VVAW-NE's juxtaposition of these two posters asserts members were angry that a plea from one of the world's preeminent spiritual leaders was being ignored by the United States, which in invading Vietnam had caused the civil war Burrows documented. The photograph also reveals that Lenny has grown his hair in rejection of both traditional masculinity and the military's insistence on a shorn head. It and joining VVAW were decisions that left him looking confident and, with his chair tilted back against the wall, very much at home in VVAW with other like-minded veterans. For more than a year, Lenny lived on the unemployment benefits to which he was entitled as a veteran so that he could show up daily at the VVAW-NE office. Chris enumerates the hours they put in. "I never got there later than 7:30 AM and I never left before 9:00, 10:00, or 11:00 o'clock at night for months, and neither did anybody else." At this point, Fred was back in the states and doing a rotation at one of the VA hospitals in Boston. No longer willing to overlook the emotional needs of the wounded, Chris and the other veterans had made sure VVAW-New England had a strong presence there. "We used to go visit them and take them out," Chris recalls of what he, Lenny, and other VVAW members did for their wounded brothers. "We'd try to get tickets to the Red Sox and take them all to the Red Sox. Anything to please them because they were great guys and they were being warehoused." He recalls the VA insisting that the wounded be back by 7 PM because they did not have adequate staff later in the evening to care for them if they were not already in bed. "You can't have any social life as a twenty-year-old if you're got to be back in your bed at seven o'clock at night."

Fred decided to start attending VVAW-NE meetings. After the success of Operation Dewey Canyon III, an effort towards which both Lenny and Chris contributed mightily, Chris by organizing the transportation for over two hundred New England veterans in what amounted to the largest delegation, regular VVAW-NE meetings had to move outdoors as the number of veterans who showed up swelled to a hundred. Determined to keep the national spotlight VVAW had finally won in Washington DC, the chapter decided to continue the mobilization of American symbols begun with Operation RAW by marching Paul Revere's famous midnight route in reverse over Memorial Day weekend. They invited the Connecticut and the Rhode Island chapters of VVAW to what they named Operation POW because "we are all prisoners of this war." Both chapters immediately agreed to help VVAW-NE bring a message to the people in the tradition of the famous patriot rider. Following the mythic version of the events of April 18, 1775, penned by poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, sixty or so veterans convened on Friday night at Concord's Old North Bridge. On Saturday morning, more veterans arrived from area VA hospitals. "People in wheelchairs, guys on crutches, paraplegics, quadriplegics, people with prosthetic devices showed up," Chris recalls. "It was something to stand there and watch these guys. You see a bunch of eighteen-year-old, twenty-year-old guys on crutches and in wheelchairs—it's astonishing." Massachusetts General Hospital donated a medical van for Operation POW. Fred, who had recently moved his young family to Lexington, which would be the march's second stop, and who had garnered so much experience in Vietnam with both physical and moral war injuries, was one of many doctors and nurses in the Boston area who volunteered to staff it. Having medical support was just one of many logistics the veterans coordinated. "I felt myself to be an administrator at this thing," Chris explains. "I was involved in trying to see where were we going next, how are we going to eat, where were we going to set up the tents, how are we getting latrines, bureaucratic stuff." He, Lenny, the chapter coordinators, and several other VVAW leaders were faced with an increasingly complicated situation as reactions from officials varied from a warm welcome in Concord to downright hostility in Lexington.

And thus one of the first orders of business on Friday night was taking a vote about how to proceed in the wake of the Lexington Selectmen deciding to deny VVAW permission to camp or perform mock search-and-destroy missions in their town. VVAW operated according to majority rule, and with only four against the idea of committing civil disobedience, the decision was made to proceed to Lexington the next day and risk a mass arrest. Before leaving Concord on Saturday morning, Lenny and a small contingent of the veterans stopped in Concord's Monument Square to perform, with permission from the town's selectmen and its police chief, a mock search-and-destroy mission in front of early morning shoppers. To make the interrogation and murder of those who had volunteered to play the Vietnamese look as realistic as possible, Lenny wore fatigue pants with a tiger stripe pattern, a tan stateside shirt, and a Boonie hat. He did not, however, pair his fatigues with the jungle boots the other veterans were wearing. Rather, he wore an elegant pair of leather shoes from the days when he worked in the shoe store, a private reminder perhaps of how far he had come in his transformation from a bystander at Arlington Street Church to activist and VVAW mainstay. Chris, who wore his fatigue jacket with its Air Force patch, helped lead a parade of veterans and the civilians inspired by VVAW's guerrilla theater to Lexington. Fred decided not to wear a white coat but rather to appear in his fatigues, carefully blousing his pants in his jungle boots so that he could be part of VVAW's political theater (page 19). Even as his assigned task was treating any medical needs that arose, he also wanted to participate in creating the illusion that Concord and Lexington had been invaded once again by imperialist troops so that residents would be prompted to feel empathy for the Vietnamese while also understanding that the US had become the very tyrants they had fought to vanquish in these Boston-area towns so long ago. Once the march crossed into Lexington, Fred felt compelled to disembark from Mass General's medical van and walk in the veterans' procession. Grabbing a stack of VVAW pamphlets, he handed them out to his fellow residents. The pamphlet explained why the organization had decided to protest the war in the town where the American Revolution began. "Lexington Green in 1775 could be a South Vietnamese or Laotian village in 1971." When the veterans finally reached the Battle Green, Lenny quickly devised an effective alternative to their usual but now prohibited mock search-and-destroy missions. When the veterans formed a circle around the Green and began alternatively chanting and singing, he decided to dance into the middle. Holding his Mattel M16 over his head for a moment, he ceremoniously discarded it in the grass. "This en masse thing creates immense energy," Chris explains of why every veteran was inspired to take a turn discarding his own weapon. Not long afterward, the still growing number of veterans were served by the town's selectmen with an injunction that significantly increased the punishment they could hand down to those who chose to occupy the Green. "This really was a heroic spot," Fred notes of the Green, recalling that eight colonists were shot and killed there by imperial troops. He recalls thinking he had a right to be there because of his own service in an American war. When VVAW took another vote about how to proceed in the face of the injunction, it was unanimous: the veterans would commit civil disobedience. Those who initially harbored doubts had changed their minds after marching in the footsteps of their patriot forefathers. The one thousand civilians who joined the veterans on the Green also believed that American soldiers had a right to have their say where the nation's founders had taken a stand for freedom. The outpouring of support was incredibly affirming, especially to those of the veterans like Chris whose families had never asked what it had been like to serve in the Vietnam War. "Everybody was happy and singing, or drinking beer, kissing and hugging each other," Chris recalls. "It was terrific." When the police finally did come hours later, Fred, Chris, and Lenny were arrested along with some four hundred other people. The town's makeshift jail was full to overflowing, leaving many on the Green frustrated that they would not have a chance to appear in court. While Chris and the other veterans were elated at the sympathetic coverage the mass arrest was receiving from the liberal press, Chris knew that once they had paid their fines in county court, they had to continue their efforts in what might be more hostile territory. The plan had always been to spend the third night on Bunker Hill, which is located in a community very different from Concord and Lexington. "This was a tight-knit, working-class community hugely represented in the service," Chris explains. "A lot of Marines come from there. Everyone in Charlestown is a veteran." He was surprised to find there was no cause for concern as the anti-war veterans approached their third camping site. "Here is some coffee, boys. Here are some donuts," Chris remembers being asked. The veterans' warm welcome in Charlestown was evidence that VVAW had brought a divided country together. For Chris, however, there was no time to celebrate this historic accomplishment. Early on Memorial Day morning, he left his tent for VVAW-NE's office to write the speech the VVAW-NE leadership had asked him to give on Boston Common during the march's final rally. The chapter's co-coordinators were moving on to graduate school and they wanted Chris to replace them. His weeks of silence now far behind him, Chris spoke readily to the thousands who joined the veterans on the Common. "The nation expects things of its young men. When they call them to arms, if they're called for legitimate purposes, people will answer. But they're in danger of having people never answer again. People are not going to feel the same about their country."

After an anti-war speech by Eugene McCarthy and several musical acts that led the crowd in anti-war songs, Operation POW came to a close. The effort had dominated the front page of New England's newspapers for four days in a row and been reported in newspapers across the country. The three chapters of VVAW that participated had done their part in keeping the public's eye focused on the necessity of ending the Vietnam War immediately. Other VVAW chapters across the country were also keeping up the pressure. By August, Chris was the coordinator of the VVAW-NE office, a job he held for two years. Lenny was elected to VVAW's National Executive Committee, where he served alongside Jon Birch, Al Hubbard, Larry Rottmann, and Joe Urgo. There was still a lot of work to do, particularly as the military was countering growing GI dissent with the automatization of the war effort. Chris put his energy into planning three days of VVAW-sponsored hearings at Boston's storied Faneuil Hall in October of 1971, to which he invited former military analyst Daniel Ellsberg to speak. A hero to many for his role in bringing the Department of Defense's secret history of the Vietnam War to the public, Ellsberg was thinking only of giving Chris his undivided attention when the two were photographed with another veteran at the hearings (page 20). Ellsberg's decision to wear a VVAW pin is further evidence of the respect Chris and the other anti-war veterans had won for their efforts over the past year. A transcript of the testimonies at what VVAW-NE called Winter Soldier II runs to 1,300 pages. In the introduction VVAW included with the abridged version it distributed, the organization asserted that the war "is being ruthlessly escalated. In indiscriminate butchery of civilians, destruction of entire civilizations and savagery of conduct, it is infinitely worse than the struggle of contending land armies." VVAW further explained that the war had become "sanitized": the "airmen, computer technicians and electronics specialists who conduct it seldom see the blood and destruction they have caused." It was not only an accurate statement but a chillingly prescient assertion of how the United States would wage war going forward. "That's one of the things I'm most proud of doing," Chris says of this effort to alert the public. That winter, Lenny joined other members of VVAW in occupying the Statue of Liberty. To signal their distress about the war, they turned every flag on the statue's plaza upside down, eventually flying one of the upended flags from the statue's head. A journalist took a photo from a helicopter that ran in newspapers around the world (page 17). "Until this symbol again takes on the meaning it was intended to have," Lenny and his co-conspirators told the press in a statement, "we must continue our demonstrations to all of the nation of our love of freedom and of America."

From Valley Forge and the Lexington Battle Green to Faneuil Hall and the Statue of Liberty, Lenny, Chris, and the other VVAW members had proven adept at marshaling the nation's symbols of freedom so that the citizenry was forced to see how far the United States had fallen from its founding ideals. From the liberal elite to the working-class, virtually the entire nation was behind VVAW weeks before the publication of the leaked Pentagon Papers confirmed what the anti-war veterans had already reported about the illegal and immoral Vietnam War. Eventually, Lenny and Chris moved on to other endeavors. "That type of rebellion is very hard to sustain," Chris notes of his and Lenny's work with VVAW. "That type of agitating and rebelling against the norms of the government and the norms of the people around you, it's very hard to sustain. It takes a lot of endurance. It's quite different than politics in the Democratic Party. You're an outsider and it becomes wearing on people." Both he and Lenny credit VVAW with replacing silence with understanding and agency. "Being against the war changed me more than the war changed me," Chris concludes. "It made me feel that there was something to stand for, that there was some hope that you could redeem your circumstances, and you could really help other people in a way that I don't think I would have understood had this not happened." "As a result of this experience," Lenny agrees, "I was able to stand up on my own two feet and say what I thought about something as big as war, which I was never able to do previously. I just never had. And I became a different person because of that." As for Fred, when asked about protesting against a war in which he had served, he says the experience changed him as well. He points to a moment years later when he took his college-bound daughter to the Boston airport.

"I thought if I was putting her on a plane to Vietnam and she wanted to get on a plane to Canada, I would have bought her a ticket." If I have learned anything teaching the literature of war, it is that while college students come to appreciate literature for its ability to create empathy for soldiers and veterans, they want to know what else besides writing novels and memoirs can be done to stop the perpetual wars that leave characters they love and many of their authors bereft of hope. Ron Kovic's memoir and other VVAW accounts like those of Chris, Lenny, and Fred show students that activism is art's powerful twin. In VVAW, students see a collective using highly creative political methods for change that they can replicate as they take up the fight for peace, racial justice, and a healthy planet. They see, in other words, that "so it goes" does not have to be our refrain. Dr. Fred G. Davis was interviewed by the Lexington Oral History Project on October 26, 1992. A video of his interview is available at Lexington's Cary Memorial Library. Christopher Gregory was interviewed by the Lexington Oral History Project on March 14, 1995. A transcription of his interview is available online. Chris was also interviewed by the author on December 11, 2011, while Lenny Rotman was interviewed by the author on November 9, 2011.

|