Download PDF of this full issue: v50n2.pdf (24.8 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v50n2.pdf (24.8 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3917

Download PDF of this full issue: v50n2.pdf (24.8 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v50n2.pdf (24.8 MB) |

Excerpt from Winter Soldiers: An Oral History of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War by Richard Stacewicz, pages 197-203.

The VVAW in New York received financial support from various organizations and individuals who saw the group as pivotal in the antiwar movement. For example, George Ball—a former adviser to President Johnson—was one of the first contributors, donating $100.

How did you get along with the peace movement?

Jan Barry (JB): In the peace movement, you ran into attitudes that ranged from not knowing what to do with us to people who wanted to manipulate us in various ways. One of the first times I walked into the Peace Parade Committee, some woman who looked very much like my mother said, "And how many babies did you kill?"

The socialist groups were always trying to manipulate us, [to] get you to join their organization. Certain things would happen, but we were so unsophisticated or inexperienced that you didn't even realize that a number had just been run on you. You just knew that something was funny.

|

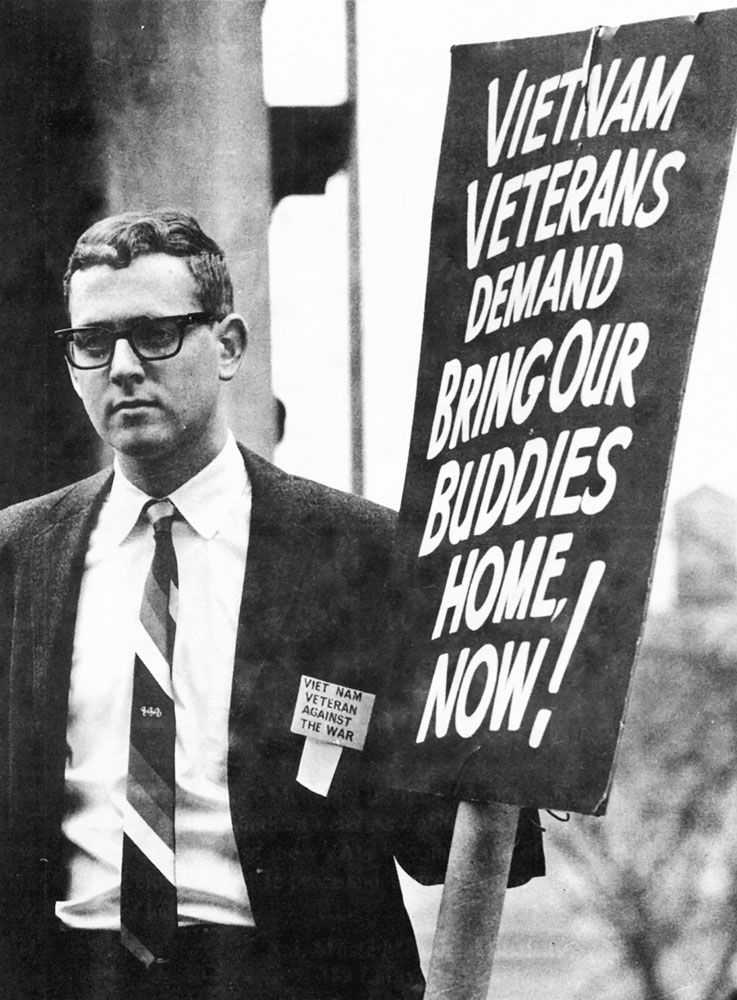

| Steve Greene of VVAW. |

You go to a coalition meeting; somebody from some really radical black group says, "Fuck the Vietcong—I don't care about those Vietnamese. They never did nothing for me." Jerry Rubin is doing crazy things that have absolutely nothing to do with Vietnam but addressing his ego. Over in the other corner is somebody else who is babbling that the whole problem is sexism. That isn't keeping those people from dying every day to say that? This is a peace movement coalition, right?

The whole point was to focus on what this crazy coalition was going to do for its next spring or fall offensive. That's what we do in the peace movement because it used the students. It took six months to organize these monsters. They thought, well, if we could get 100,000 people in Washington, that will end the war. If we get 200,000 people ... if we get 500,000 people ... then the moratoriums would get 1 million people to surround the White House, it will end the war.

I was much more interested in: Where can I go and talk to two, or three or four conservatives, and change their minds? In the middle of all of this, you had a group of veterans, who psychologically and politically were bouncing all over the place.

One of the reasons I felt so strongly about forming VVAW was to provide a forum for people to come to and utilize a platform. Other people came for all kinds of other reasons. What I found most remarkable is: Even with all these various places that people were coming from, it still grew to be fairly basic VVAW philosophy that we're going to do this nonviolently, which is remarkable. You're talking about people who had all been trained to kill people. Many of them did, repeatedly.

We were going to level with the American people and tell them things, even if they didn't want to hear about them, like war crimes. We discovered early on, when going around speaking, that you couldn't even touch on the subject [war crimes]. People didn't want to hear that. "There's no way that American boys would ever do something like that!" Everybody—liberals, conservatives—just cut it right off. You felt stunned. This is what had been the reality over there. You're simply reporting the reality, and people say, "No, it couldn't have happened."

We constantly talked about how you turn things around imagewise. We didn't use the word "jujitsu," but it was the same kind of principle: to turn around a lot of these things so people would turn around and say, "Wait a minute. What? What did you just say?" Get them to think about it.

Sheldon—Shelly-Ramsdell grew up in Algonquin, Maine. He joined the Navy in 1954; served on an aircraft carrier patrolling the waters around the Philippines, Indonesia, and southeast Asia; and was discharged in 1958. He was interviewed in a coffee shop in San Francisco.

Sheldon Ramsdell (SR): One day—a Sunday, I think—there was a draft-card burning in Union Square [in] 1967, and I went down out of curiosity. I'm wearing a suit and tie; red, white, blue; I think I even had an American flag pin on. There was Carl Rogers and Jan [Barry] Crumb and David Braum standing there, and they had signs that said VVAW.

I got very angry and upset and went over there and talked to Carl and said "You guys for real? I mean what the fuck is this? What's going on here? I don't believe this. Why would they be burning draft cards anyway? They'd already served!"

He says, "I was a chaplain's assistant in Vietnam, and what about you?"

I say, "I've been in the Navy, but I got out in 1958, for crying out loud."

He says, "Well, you're a Vietnam vet."

I say, "I'd been overseas on a carrier and we'd been doing border reconnaissance bombing and I was processing gun camera film." I didn't ask what we were blowing up or who we were bombing. Apparently it was Laos. The Pentagon Papers explained it to me, finally, but I was never convinced that I was actually a Vietnam vet until Carl had insisted.

So I said, "Jesus, I've been looking for you. I've been pissed off at Johnson and all this bullshit—the lying, the deception. This war should have been won long ago."

He says, "Exactly."

Then I met Jan (Barry) and we got together and had little meetings up on the West Side. There were three or four, maybe six of us at the most. I said "We've got to do media. I've been trained in it in the military and at Union Carbide." I studied it at Carnegie Endowment. I had a job in public relations and I had studied photography. I had all of that behind me, and so I said, "Let's put it to work against this war policy."

JB: When we first started out, there were a small number of people in VVAW, so it made sense that we go on television and talk programs and talk anyplace we could find an audience. Our goals were to educate the public to the reality of what was going on in Vietnam so a better decision could be made. We were calling for—I think the tag line of the thing was—"Save our buddies now; withdraw them now." No one else should die in a war that the American public didn't vote for. This wasn't really clear to people. There had been no vote on this war.

In that first several months, well into the beginning of 1968, our whole goal was to utilize those people we could get motivated, to do their research and speak. The average GI doesn't know all these facts. You can't simply say, "I was out there, but I don't really know anything about the Geneva Convention; I don't really know about Ho Chi Minh; I don't really know about how we got into Vietnam." We insisted ... that you get educated.

If the people knew the reality of Vietnam, what would they do?

JB: They would be talking to other people, and ultimately there would be a change in policy. None of us had a degree in political science. We had the same general sense as most people. You change the public attitude in this country, things change. It wasn't any grander than that.

To give you a sense of strategy ... When we first started, we wore suits and ties. [It was] a conscious decision that we're going to show people that we're serious. At that time in American society, if you were a serious person, you wore a suit and tie to do serious business.

We had a big debate about whether or not to wear our uniform, because it was against the law to wear a uniform after you were no longer on active duty. I think the first demonstration that we all decided that yes indeed, if you wanted to do it, you could do it, was in April of 1968 in New York. Some people showed up in dress uniforms. We're not talking about the grungy jungle shit. Full-dress uniforms. There's a couple of pictures around with guys standing with VVAW banners and flags in full-dress uniforms. You can imagine the effect this had upon cops and lots of other people. Holy shit! These people are for real—a whole bunch of medals.

We researched the Geneva accords. We went out and debated people from the State Department and said, "You made an agreement with everybody that in 1956 there would be these elections. What happened to these elections?"

The amazing thing was, in 1967, the White House was so conscious of this, they would send someone out from the State Department to debate people in teaching kinds of situations. On one occasion, it was a Democratic Party gathering in Long Island. I can remember Paul O'Dwyer, who later became the City Council president, was at this meeting on the dais. A congressman representing LBJ shows up drunk. When I had finished speaking, he ran off—literally jabbering, howling, and screaming—off the stage. He didn't know what the hell he was talking about. He hadn't been to Vietnam. He had none of the facts.

On another occasion I was asked to speak at the New York State Maritime Academy in a teach-in to the cadets. The other speaker was a major in the Marine Corps from the Pentagon. Same thing happened. He hadn't been in Vietnam. He didn't have his facts straight. I stood there correcting him about what the Marines did on which dates in Vietnam.

We would go anywhere that we can get an invitation. I did radio and television programs in New York, Philadelphia, [and] upstate New York. I did speaking engagements as far north as Boston and later on in Wisconsin. As far as most of us were concerned, every audience at whatever age was an important audience.

We went on radio programs, which were just like today: most of them were right-wing radio programs. We'd show up and start debating these people. They would bait us. As an example, someone would say, "We're going to get you. We've got files on you people," which scared a couple of people. I didn't see anything in my life that I was worried about. There were some people who were closet gays who did get a little worried. So the people who did have something to be concerned about got a little shaky when somebody said, "We've got files on you."

On another occasion, it was a television program, David Frost. At the commercial break, the guy next to me turns and says, "Why don't you go back to Russia where you came from?" I said, "I don't come from Russia ... My mother's one of your greatest admirers." This was some religious nut. You never knew who you were going to be put into a debate situation with. It was great. I could care less who I was debating.

SR: In the beginning, we were a media group, doing a thing on morality. Carl, David, and Jan did the David Susskind show. Susskind was very, very good at this. We did it twice, in fact. I was selling oranges all of a sudden. It was a product. I went and listened and said, "Great, great, but who's going to believe it? Who even believes that these guys are veterans that have been in the war at all?" You can talk your head off and nobody would listen.

We went to Long Island, to Hofstra University, for example. We had rocks thrown at us, chased out of town, police escorts. We were communists and all this shit. I'm outraged. They'd never even heard that these guys were in Vietnam, or even that I served, for Christ's sake. It devalued us, and I really felt like we really didn't have a message for anybody here.

The earliest members of the organization, like Sheldon Ramsdell, felt frustrated by the disregard and disrespect they seemed to be getting. They had tried to engage the public through established channels but found their way blocked by many Americans' inability to hear what they were saying. The cold war consensus was so strong in some quarters that, rather than listening to those who had served, various segments of the public attacked VVAW members as communists or malcontents. Nonetheless, VVAW persevered. In 1967 VVAW slowly grew, attracting the attention of other veterans, and civilians as well.

Copies of Winter Soldiers can be purchased through Haymarket Books at www.haymarketbooks.org/books/859-winter-soldiers.