|

Young Man Goes To WarBy Allen Leonard MeeceI enlisted in the US Navy in 1962. I joined to learn a trade and see the sea. I did not join the service to kick ass halfway around the world at the whim of big shots who control the government and hate socialists of any kind. I trust in peace but I'm not a peacenik. I would gladly defend democracy with a gun if my country were invaded by armed forces. Damn right. But today it seems that American democracy is being attacked by unarmed internal forces like those big merchants who love fascism, the system that marries government with commerce and strives to control the lives of consumers and producers worldwide. I can't force them to behave but I can right their lies and vote carefully. They hate that. They rig elections to fight the smart votes.

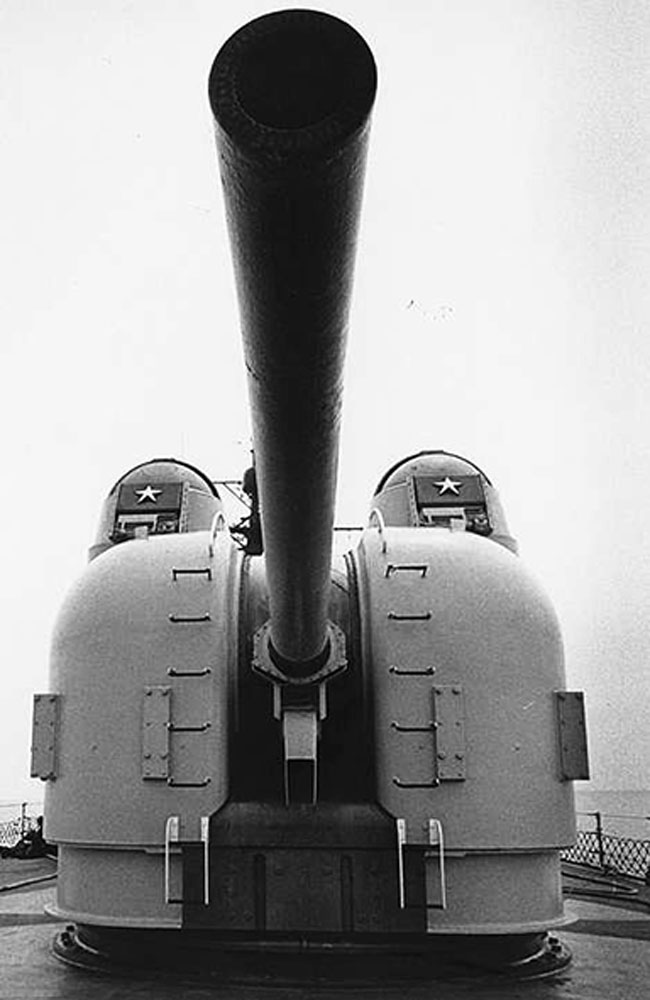

I would not have donated four years of my life had I known that the Central Intelligence Agency was violently enforcing the big shots' goals and covertly provoking war against the Vietnamese who had defeated the French capitalists eight years earlier and were now displaying the nerve to try to run their own country. "Oh no you don't," said the sneaky bunch whose career assignment was, and always will be until they're abolished, to exploit every sovereign nation in the world by helping the big corporations to politically and commercially dominate mankind. [Now you know what the slogan, "protecting American values" means.] The CIA began their Vietnam War with "Operational Plan 34A." It's gone now but its principles of de-stabilization are still working where countries took their oil resources away from big oil big shots. It's a dirty tricks campaign of sabotage and anonymous acts of war. Those barbarous crimes were deceitfully termed "military conflicts." Subservient US advertisers' media accepted that fake phrase like a sizzling filet mignon on a platter. "Mmmmm, free news," they lazily said. "Don't need to check it or pay a reporter on the scene. Boom! Just copy it down in your own words and you've got a cheap news story that people will have to believe because it's 'authoritative.' We can treat it like it's the pure, unadulterated, truth." So, in 1962, there was not one jot of public information about such a huge thing as my country creating a war of great death. On that basis, I joined the military. Two years later, I found myself shooting PT boats in the Tonkin Gulf. In Tin Can my current Vietnam naval novel on Amazon.com, I describe how it felt to be an innocent kid riding a destroyer through the night toward a military conflict: "What's a conflict? Fencing? Jousting with cushioned lances? Suction cup arrows and rubber bullets? Maybe it's like war movies with explosions that can't kill anybody and misses the good guys. Movies show and confirm that we'll be okay because we're the good guys." I hadn't learned yet that movies are just another corporate media. Near Da Nang, my ship dropped anchor in the war zone in 1964. We pulled hazardous duty pay, twenty-five dollars a month for the risk of being killed. That's how much they thought of our contribution. We parked the ship five nautical miles offshore from the lovely hills of Vietnam and began pumping five-inch shells into the leafy canopy. We received three hot meals a day, slept on clean sheets, and we had a free coke machine. The machinist mates couldn't keep it working and it dispensed warm brown syrup. Disgusted users would leave their coke cups all over the ship and this angered the Executive Officer, the second-in-command of a warship shooting at people in a self-proclaimed war zone. He wrote this in his Orders of the Day, "Due to paper cups littering the ship, the coke machine is no longer free but charges one nickel per drink." It was stupid and it was wrong, period. Crew members couldn't admit what they were doing. They ignored the gun mounts banging on the steel bulkheads around them. In Tin Can, chapter 3, Tonkin Gulf, I describe the mood onboard the ship during shore gunfire support: "... the USS Abel bombarded the rainforest for six days and no one talked about the gunnery. The crew ate and slept and worked to the jolt of big-bore rifles firing heavy projectiles every ten minutes. There was nothing you could say or do about it. It was Navy policy to shoot people in the woods. Their destroyer was doing what it was meant to do; destroying life and property, consisting of huts, canoes and maybe a few tricycles, maybe children on them, you couldn't tell from way out here. "At noon on the seventh day the gunfire stopped. Jack and Obie went up to the flying bridge to survey the results: None. The puffy green jungle parasol had swallowed the Abel's shots like popcorn farts." Then I wanted out of the service. Enlisted people weren't allowed to voluntarily quit. We could volunteer to get in but not to get out. Even after the military moved the goalposts way outside the park of human decency, anyone could legally shoot us if we walked away from a war zone, even if it was an insane war in a fake zone. You got killed or you got a discharge. Involuntary servitude means Total Ownership. Not Partial, Total. When I say I was in Vietnam, I quickly add that I was in the Navy, the offshore "blue water Navy." The usual image from the Vietnam War is of firestorms in the jungle. It wasn't like that in my Navy. We fought by remote control. I did not realize back then that I was getting a guilty conscience from the experience of crewing a ship that was killing unseen people for months from a safe distance. It induced a subconscious post-traumatic disorder that turned into twenty-five years of chronic drunkenness for which I apologize to all whom I hurt or baffled. It won't happen again to me or any generation of good young people, I sincerely hope. The United States ship took me where I wasn't wanted, the Tonkin Gulf, and made me fight for my life to get out safely. That's the pathetic simplicity of war. The answer is; don't sign up to let the owners carry you where you don't belong. Make the greedy freaks of commerce leave other people alone. It's not rocket science. Unless warriors threaten your borders with weapons, leave them the flock alone. Fear the horror of an unjustified war more than you fear those whom the owners will call "Those People," the "sub-human socialists" and those whom your handlers give you some peanuts to make disappear. All I could do, much later, was to write a darn good literary novel that got it off my chest and helped me feel better. In the book, I imagined that I fomented a mutiny and took my warship out of that long, slow-motion atrocity called, by the people who bore it, the Vietnam American War. Former Petty Officer Allen Meece was in the third Tonkin Gulf Incident and wrote Tin Can, available at Amazon.com.

|