Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3428

Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB) |

|

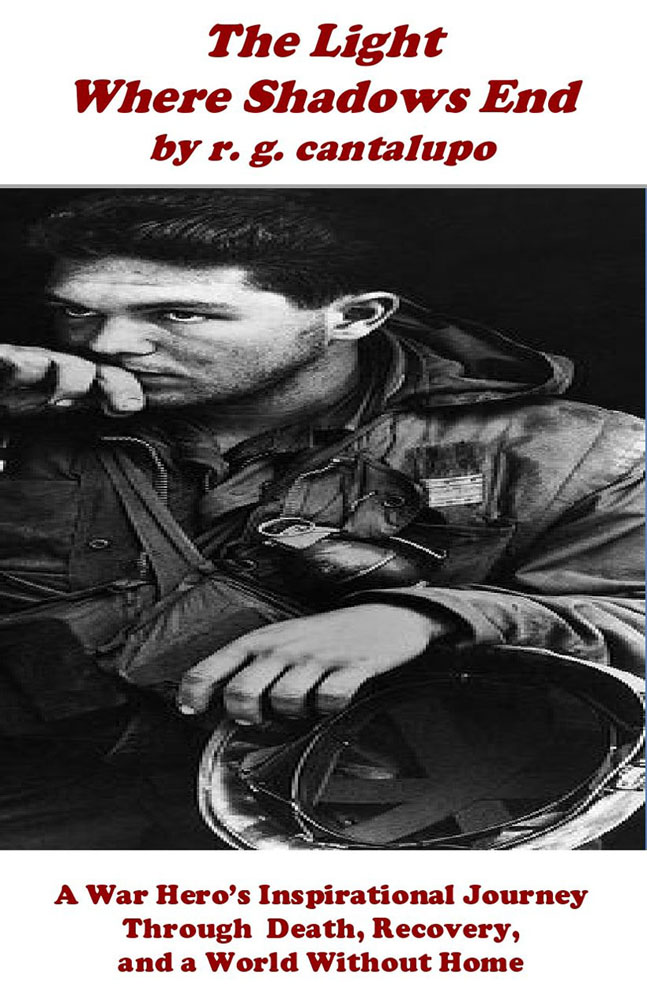

The Light Where Shadows End: A War Hero's Inspirational Journey Through Death, Recovery, and a World Without Home

by r.g. cantalupo

(New World Publishers, 2015)

A member of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, the author took part in the 1971 Winter Soldier Investigations where he confessed to committing crimes and atrocities. A Radio-Telephone Operator (RTO) with the 25th Infantry Division in 1968-69, cantalupo (a nickname, actually Ross Canton), served in Vietnam and was awarded a Bronze Star with a Combat V and three Purple Hearts. He describes himself as a war criminal who fired white phosphorus mortars and called in napalm bombs on civilians using weapons banned by the Geneva Convention.

He returned to the scene of his action in 2015 "to survive my looming suicide...to Trang Bang where Nick Ut photographed the Napalm Girl." That was also where he ordered villagers to lie down while they destroyed their village and where "Lonny, Baby, San, Devil and I lay dying not for God, or flag, or country, but simply because we were The Chosen, draftees offered up from poor black, brown, or white families by an upper-middle-class draft board that didn't want to take sons from their own."

He describes his boot camp training droning into him like a mantra: "They are gooks, dinks, commies, savages, nothing resembling us, nothing close to human. And, it worked. When I was shooting at a cardboard man, when I was stabbing a dummy to death with a bayonet, when I was on the edge of terror, it was the only voice I heard. But four months in Vietnam changed me. The kids along Highway 1 chanting 'GI Numba One' as they begged chocolate bar or cokes looked no different than the kids from my tenement, Asian rather than black, or Puerto Rican or Pollok or Jew. They were hungrier maybe, more desperation in their eyes, but under the grime and stink, they were no different than the kids I grew up with carrying hopes and fears and dreams. And so I heard a different voice, my own. How long does it take to kill a man - from inside? How long before I was no longer a man but a rifle. A bullet, and I inside a soulless body?"

After his good friend Lonny is killed when he made eye contact with an enemy soldier who was badly wounded and groaning in the Elephant grass, cantalupo raised his rifle, "I put his head in the crosshairs, held my breath, and put my finger on the trigger guard. I didn't squeeze the trigger. I couldn't. Not anymore. Lonny was dead. Nothing I could do would bring him back. Not killing this soldier. Not killing the whole fucking North Vietnamese Army. Lonny was dead. Shot in the throat and chest by his own men. Friendly fire. Friendly. As if killing was somehow friendlier if done by your own men. And who was to blame? The soldiers on the perimeter who opened fire from fear of being overrun? The C.O. who sent us out? General Westmoreland? Nixon? Kissinger? The Pentagon? The Army? The rich? The whole fucking US of A? My mother? My war-hero father? Yes, everyone was to blame. Everyone carried Lonny's blood on their hands. I lowered my rifle. I was done. I was done with killing, done with death, done with war. For a long moment, the wounded soldier held my eyes, then he turned and slowly crawled away."

He recounts his horrendous injuries from a mortar exploding a few feet away that hurled his body into the dark sky and then crashed down leaving him covered in warm blood. He remembers a nurse nicknamed, Peaches, who helped him through hours, days and weeks of care and with whom he says he seriously fell in love. "And then I rose. Above my body. Above my life. Is this my soul parting from my flesh, my spirit rising toward eternity, flying through the tunnel of white light toward people I loved? I rose in darkness, in shadow, the body below me — my body — graying to a shade, the medic slowly dimming to a hazy silhouette. I rose, but my wounds did not fly away on angel's wings, nor did I see my mortal life bleeding into light as if I were eternal. I merely slipped in and out of a world filled with fire and burning pain."

A film crew from Vietnam TV International recorded his anguish following his journey toward a reconciliation meeting with former members of The People's Army against whom he fought. They shared the truth of where the People's Army hid in tunnels awaiting to attack and used a map to describe each of their locations in battles. After awkward embraces, they shook hands and said goodbye through the pain such a meeting engendered. The war's legacy in Vietnam, cantalupo says, includes "leaving hundreds of thousands of unexploded bombs to kill more children," as well as "fourth generation birth defects and genetic mutations caused by our massive spraying of Agent Orange." That situation "will not allow for my reconciliation." This was the most profoundly moving memoir I have read on Vietnam, showing how a man changed from a war criminal to a sensitive human being aware he was lucky to have survived and gained an inspiration and awakening that changed his life.

Dan Lavery graduated from Annapolis, navigated a jet, then a ship to Vietnam. He resigned, joined VVAW, and became a civil rights lawyer for Cesar Chavez's UFW, the ACLU and in private civil rights practice. His memoir, All the Difference, describes his change from a pawn in the military to crusader for justice. www.danielclavery.com