Download PDF of this full issue: v27n1.pdf (9.8 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v27n1.pdf (9.8 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=275

Download PDF of this full issue: v27n1.pdf (9.8 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v27n1.pdf (9.8 MB) |

"I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity." --Dwight D. Eisenhower

It was September of 1970. I had just been discharged from the Army and was leaving Fort Dix, NJ. Uncle had just let me out thirty days early to go to college in Minnesota. As I got to the post gate, something came over me. I had just spent almost two years of my life in Uncle's army and I felt confused, used, pissed off, and at the same time, relieved.

I knew when I was drafted that my life after high school was going nowhere, yet I did not want to be in the military. I was young, naive, and impressionable. Even the word "Vietnam" scared the hell out of me. But now it was over. Or was it? The army had gotten what it wanted out of me, I'd served my country, yet I had this hollow feeling inside.

Both my parents were W.W.II veterans and were proud of that fact. Shouldn't I be proud too? After all I had served my country, but to what end? Why were we in Vietnam? Why were boys my age dying in droves? Why was the Vietnamese population being killed in a genocidal fashion? Why are people in the streets protesting MY government's actions? Why were students being slaughtered on their college campuses? What has happened to this great country I grew up in? Well, maybe that's the way life is, or maybe MY government had lied to me. All I knew was that Uncle used me and now had no further use for me. Given what I could expect from the GI Bill, I realized I had no real value now that I was a veteran.

At this point I stopped my car at the unguarded gate, emptied my duffel bag of all its military garb, sprinkled the clothing with lighter fluid and set it afire. As I sped away and watched it in my rear view mirror, all I could say to myself was: Fuck them. I was a civilian now, not thinking that I was in the inactive reserves and if caught probably could have been right back in Uncle's army.

By the time I got to Minnesota to attend Mankato State University, I was really anxious. Here I was a 22-year-old freshman. I don't think I'd ever felt this alone. At least in Uncle's army I had buddies I could count on. Now what do I do? I thought. When classes started I felt even more alone. What was I doing here with all these kids who didn't have a clue about what was going on beyond their academic borders? So I became a loner, went to classes, and got high every chance I could. But no matter what I did, I could not get away from the Vietnam War. It was all around me. On the news, in the movies, on campus, in the music.

In the Spring of 1971, I felt that there had to be other vets who had the same values I had. After all there were a lot of vets on campus. In the student union one day I ran into a Vietnam vet who invited me to a Vets Club "smoker." I got to the meeting and I could have sworn I was at a fraternity meeting. Guys talking about what they were going to do at the fraternity charity festival. No talk about the war or its effects outside of ridiculing the students who were protesting it. Come on, throw me a bone, what is this: VFW, the younger? Just then I spotted another vet who looked just as bewildered as I must have appeared. He told me about a "Teach-In" that would be happening later in the week. The focus was on the campus antiwar movement and it was being sponsored by the Student Mobilization Committee (SMC).

It was at the SMC Teach-In that I first heard of Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). There was an open mike, and as I listened to fellow veterans, I realized I was not alone in my thoughts and beliefs. I got up and talked about the mangled bodies that we came across daily in air evacuation and how fellow GIs went literally crazy as part and parcel of their role in the war.

I was approached by a few veterans who had spoken earlier about their roles in the war and how they had become antiwar vets. They had just started a local chapter of VVAW. Always the hesitant one, I hemmed and hawed about getting involved. I did agree to go to an antiwar march in the Twin Cities that weekend.

At the antiwar march in Minneapolis, the Vietnam veterans were to march in the front. There were hundreds of us. I couldn't believe it. I was able to talk to a number of VVAW members from across the state. Finally I realized that I was not alone in my thinking. I found what I was looking for. It was here that we organized for Dewey Canyon III, a limited incursion into the foreign land of Washington, DC, in April of 1971. It was here that I joined VVAW.

Dewey Canyon III was amazing. Over 1,000 Vietnam vets from all over the country demonstrating against the war. Guerrilla theater, "lobbying" Congress, testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, marching on the Pentagon, occupying the Supreme Court steps, being locked out of Arlington National Cemetery, and -- perhaps the climax to this emotional roller coaster -- the returning of medals from the war.

The irony of the week's activities was the U.S. government's fencing off of the Capitol from its veterans. This demonstrated that the government did not know or care what they had created by sending its boys off to an undeclared and undefined war. All the government knew was that the contingent of veterans camped on the mall was the first time in history returning servicemen had voiced opposition to a war that was still raging.

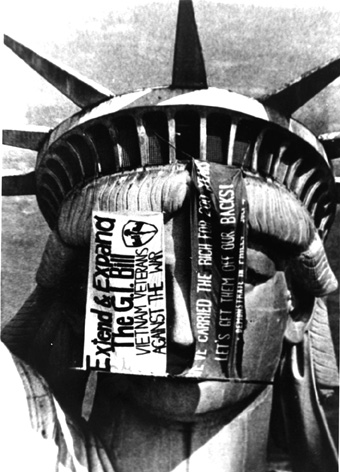

VVAW Takeover of the Statue of Liberty, 1976

Upon returning to Minnesota, our campus VVAW organized, was recognized as a "legal" student organization, membership grew and a number of us ran for and won seats in the Student Senate. We were gaining local political clout and were getting our message out about the "real" war in Vietnam. We were invited to address high school and college classes all over southern Minnesota, and students and teachers alike were listening.

Between 1972 and 1975 our local VVAW organization became the leader of the antiwar movement on campus. The Mankato office also focused on other issues of concern to veterans, such as bad discharges, SPN codes, jobs, amnesty, and military recruiting on campus. The Mankato VVAW office organized a statewide VVAW meeting that was accompanied by a peace conference sponsored by VVAW and the Mankato State Student Activities Office. Members of the VVAW national office attended and both John Kerry and Al Hubbard of the national office addressed the conference.

In 1975, I withdrew from my activities in VVAW in order to finish graduate school. Nixon was gone, the war was finally winding down, and with a family to care for, I had to move on. Of course this didn't mean that the VVAW values embedded in me were gone. I was just in hiatus, probably for longer than I will openly admit. Nor did this mean that I no longer had the unannounced visits from the FBI. VVAW was still considered a threat to J. Edgar and labeled a subversive organization, and of course I needed watching.

It is now over twenty-five years since I first became involved with VVAW. Do I still consider myself a member of VVAW? As we say in Minnesota: YOU BETCHA. I have considered myself a member since that fateful day in 1971. There are a still a number of VVAW members from our college years that get together to discuss the war and its impact on our lives, families, and the world.

The impact of Vietnam will be with all of us for the rest of our lives. We can take pride in the fact that VVAW played a large role in ending U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Unfortunately, the same military madness still hovers over Washington, DC, almost as if we learned nothing from Vietnam.

What does VVAW mean to me in 1997? Simply put, it means a voice for veterans that are not enamored of war and military achievements. It means striving to redirect government resources so that the 30+ percent of homeless Vietnam veterans can find homes, jobs, and health care. It means a world without war for our children and grandchildren. It means peace, and unfortunately there is still plenty of work to do.

As Graham Nash so aptly wrote in 1988:

Men who were fighting for all of our lives

Are now fighting for children, for homes and for wives

Fighting for the memory of all who fell before

But the soldiers of peace just can't kill anymore