|

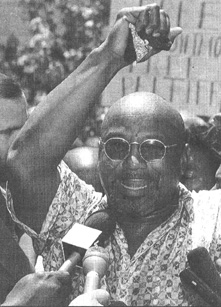

Freedom But Not Yet Justice For Geronimo PrattBy Ben ChittyOn June 10, 1997, after more than a quarter century in California prisons, Vietnam veteran and Black Panther Party leader Geronimo ji-Jaga (aka Elmer Pratt) was released on $25,000 bail, while the Los Angeles District Attorney appeals the judge's decision to overturn Pratt's murder conviction, and then decides whether to try him again for the 1968 Santa Monica murder of Caroline Olsen. If the DA goes back to trial, the case will be tough to make. The only eyewitness, Olsen's husband, is dead. The only person ever to hear Pratt confess, Julius Butler, has been exposed as a police informant. And a retired FBI agent is prepared to testify that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had monitored Pratt in Oakland near the time of the murder - over 300 miles away. More than reasonable doubt, even after all these years. A good thing. Some slight justice done at least and at long last. After his release, Pratt spent some time with his wife and children, visited his mother back home in Louisiana, and has since been speaking around the country. Maybe there will even be a movie. Pratt has already paid a high price for justice: the loss of his first wife and unborn child, decades of incarceration, separation from his family. If now he gets a little celebrity, some money, he's earned it - but getting paid is not exactly what Pratt's about. When Pratt speaks, he talks about people learning their own history, about becoming disciplined. He tells folks to dedicate themselves to liberation, to work to put an end to crack use, to show respect for elders, to turn the "gangster mentality into a revolutionary mentality." An unreconstructed rebel still. Pratt should know. He survived one of the harshest campaigns of repression ever seen in our country, and perhaps the most sophisticated - an FBI counterintelligence program, "COINTELPRO: Internal Security-Racial Matters" as it was labeled in the FBI files. The FBI has always hunted subversives, from the "Red Scares" of the first World War to the anti-communist crusades following the second. For Director J. Edgar Hoover, communism was the gravest threat to the nation, worse than organized crime, drug trafficking, or racist vigilantes. At the beginning of the 1960s he added to his list the movements for Puerto Rican independence and for Negro civil rights. But by 1967 Hoover had decided the most serious domestic threat to national security came from the black liberation movement. He ordered a new COINTELPRO, directed against "black nationalist hate groups." Though this rubric covered organizations as diverse as the Nation of Islam, the Student Non-Violent (later "National") Coordinating Committee, the Republic of New Afrika, and assorted student and campus organizations, the main target was the Black Panther Party. In November 1968 Hoover circulated a memorandum directing his agents "to exploit all avenues... of creating dissension within the ranks of the BPP," and instructing local offices "to submit imaginative and hard-hitting counterintelligence measures aimed at crippling the BPP." One of the first such measures was the December 1969 execution of Chicago Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in a police raid coordinated by the local FBI office and assisted by an FBI asset who had infiltrated the Party to become its Chief of Security and Hampton's bodyguard. One of the Bureau's last operations against the BPP also climaxed in an execution - that of George Jackson in San Quentin prison in August 1971, during an escape attempt orchestrated by another FBI asset who provided a defective revolver. The case of Pratt and the Los Angeles Panthers is equally deadly, and instructive. The FBI deployed the usual tactics: surveillance and harassment, propaganda and disinformation, infiltration and provocation, and assassination. The purpose of surveillance was as often just harassment as intelligence. But plain harassment was common enough, and the LAPD with its more than half-century history of brutal and racist corruption was especially cooperative. Pratt was arrested four times in 1969 - three times on purely bogus charges (possession of explosives, kidnapping and murder). Infiltration and provocation were common too. Charles Garry, a movement lawyer, estimated in 1969 that there were 60-70 police agents active in the Party nationwide. In LA, Julius Butler, ex-cop, police informant, and later the main witness against Pratt, was well known as the man with the biggest mouth at confrontations with the police. But the most effective tactic involved propaganda and disinformation. The FBI fostered a long-running feud between the Panthers and another militant LA group, the US ("United Slaves") Organization. Members of each group were denounced to the other as police agents, posters and letters were fabricated and delivered - all elaborate ruses designed to provoke attack and retaliation. It worked very well: US militants killed Panthers at UCLA in January 1969 and wounded two and killed a third in San Diego in August. More US militants and Panthers were likely killed by each other than directly by the police. Another disinformation campaign aimed to split the Panthers. Pratt himself had to pass a number of "loyalty" trials by the BPP hierarchy. Four days after the Chicago assassination of Hampton and Clark, the LAPD staged a copycat raid on the local Party headquarters. As Hampton had been specifically targeted in Chicago - his bedroom mapped out by an informant for the FBI who briefed the assault team - so Pratt was targeted in the LA raid. The police informant was Cotton Smith, third ranking officer in the LA Party, and the assault team sprayed Pratt's bed with bullets. They missed killing him, since Pratt slept on the floor instead of the bed, to relieve the pain of a back wound from Vietnam. But all the Panthers were arrested for assaulting the police. Pratt remained in jail for a couple of months before being released on $125,000 bail. After a national speaking tour, he returned to LA and dropped from sight. Then in August the FBI staged the action at the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael, in which George Jackson's 17-year-old brother Jonathan (along with his hostage and two inmates) was bushwhacked and killed by sharpshooters bussed in from San Quentin. Pratt took off for Texas, and missed a court date on the explosives charge. After considerable discussion between the FBI and the LAPD about the best case to make against him, Pratt was indicted in December 1970 for the murder of school teacher Caroline Olsen during a robbery on a tennis court in Santa Monica. LAPD detectives seized Pratt in Texas and returned him to California. Shortly afterwards Newton expelled Pratt from the Party, and the Panthers refused to corroborate his alibi for what was called the "Tennis Court Murder." For more than a year, the various legal proceedings against Pratt went in his favor. Some charges were dismissed, others went to trial but ended in acquittal; the May 1971 trial on the December 1969 shootout case ended when the chief government witness was exposed as an FBI informant. Then in November Pratt's wife Sandra, eight months pregnant, was murdered - shot five times at point blank range and dumped alongside an LA freeway (perhaps by US militants - the murder was never seriously investigated). The "Tennis Court Murder" case came to trial in June 1972. Pratt was convicted of first degree murder on July 28, and got the usual sentence: seven years to life. And by the end of the year, the California left - a broad coalition of progressive and revolutionary organizations - had been dismantled and smashed. So Pratt may now be free, for a time at least, but the operation was still a success. To quote Ward Churchill, historian of the COINTELPRO on the American Indian Movement, "the movement for social change loosely described as the 'New Left' had been shattered, its elements fragmented and factionalized, its goals and methods hugely distorted in the public mind, scores of its leaders and members slain, hundreds more languishing in penal institutions as the result of convictions in cases which remain suspect, to say the least." After the embarrassing 1971 release of documents stolen from the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, Hoover declared COINTELPRO suspended. In fact the program's greatest and bloodiest coup still lay ahead - the repression of the "Indian insurrection" at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 1973-76. And counterintelligence programs continued into the 1980s and 1990s; the Bureau has run operations against Latin American solidarity activists (including VVAW during the 1988 Veterans Peace Convoy to Nicaragua), radical environmentalists (such as the bomb attack on Judi Bari in May 1990 during Earth First!'s Redwood Summer campaign), and opponents of the Gulf War in 1991 (again including VVAW). So, back to basics. The US government considered that it was more important to smash the Black Panthers than it was to stop police brutality or drug trafficking. That government policy cost Pratt 27 years of his life, and more. Now he's out. The police are still arresting, beating, killing young black men in large numbers. The drug trade is the most lucrative profession in the ghetto. Who profited from that policy? For the government, the question had never been justice or peace, or even stability and prosperity - just power. That time they won. Time will come again. The Black Panther Collective in New York City has started a new "Brutality Prevention Project" - patrolling the community and monitoring police behavior with video cameras. We get another chance to pay attention to the experience of Geronimo ji-Jaga, once also known as Elmer Pratt. This article is based on current wire service, newspaper and magazine accounts, and on unpublished material on political repression collected by the late Frank Donner of Hamden, Connecticut, and on Agents of Repression by Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall (South End Press, corrected edition 1990 - the quote is from p.61). For more information about the NYC Panther police patrols, write Black Panther Collective, P.O. Box 20735, Park West Station, New York, NY 10025-1516, or call 718-390-3555.

Ben Chitty is a member of the New York area Clarence Fitch Chapter of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and a Navy veteran of two deployments to Vietnam.

|