Download PDF of this full issue: v42n2.pdf (5.4 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v42n2.pdf (5.4 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=2161

Download PDF of this full issue: v42n2.pdf (5.4 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v42n2.pdf (5.4 MB) |

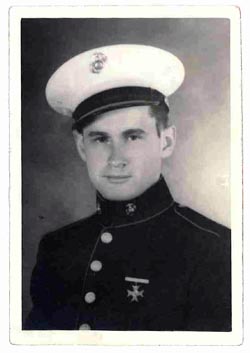

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, my father, Francis Anthony Boyle, after whom I am named (being the oldest of my parents' eight children), applied for admission to Officer Candidate School for the United States Marine Corps. After an extended period of investigation, he was eventually rejected-telling me it was the most disappointing day of his entire life. He was not given the reason for this rejection. But as a child he had rheumatic fever, meningitis, and polio. As a boy he had to walk around with crutches and only gradually managed to wean himself from them. The rejection by the Marine Corps Officer Candidate School undoubtedly saved my father's life and thus made mine possible. The chances of survival for a young Marine Corps Officer in the Pacific Campaign were infinitesimal. They were expected to lead their troops into battle from in front of their men.

|

Despite his deep disappointment and his physical limitations, my father then enlisted in the US Marine Corps on 14 July 1943 at the age of 22 and agreed to serve for the "Duration" of the war. By contrast, I entered the Harvard Law School on about 7 September 1971 at the age of 21. I thought of my father a lot during that first year of law school. At about my age, he was fighting for his life in the jungles of the Pacific. But my father would have wanted it that way for me.

According to his Honorable Discharge papers (A108534, Series A, NAVMC70-PD), Marine Corps Records, and war stories, my father invaded Saipan, Tinian and Okinawa. According to my father, after the battle for Okinawa, all but two Marines from his original Company were either killed or seriously wounded. The Marine Corps then ordered my father and his buddy to begin training for the invasion of mainland Japan with a new unit where they were scheduled to be among the first Marines ashore because of their combat experience.

Instead of being among the first US troops ashore to invade Mainland Japan, my father was among the first US troops ashore to occupy Mainland Japan. According to his Marine Corps records, my Father "arrived [by ship] and disembarked at Nagasaki, Kyushu, Japan" on September 24, 1945 — just after that City and its civilian inhabitants had been obliterated by an atomic bomb on August 9, 1945. It must have been a truly horrific sight for a young man from the Irish Southside of Chicago to have witnessed and dealt with psychologically.

By the end of the war I suspect my father had become inured to inflicting death and destruction upon the Japanese Army and all of its accoutrements. But this scene was existentially different: a devastated City where approximately 80,000 civilians had just been exterminated. At the time my Father must have contemplated what damage one atom bomb could inflict upon his native City of Chicago and its beloved inhabitants.

After his Honorable Discharge from the Marine Corps on 16 January 1946 as a Corporal with his "Character of service" rated as "excellent," my father attended Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois and graduated from their Law School in the Class of 1950, shortly after I was born. He went to work as a plaintiff's litigator for a law firm in downtown Chicago where, his hiring partner told me, he was very aggressive in court and otherwise. Eventually, my father opened his own law firm as a plaintiff's litigator in downtown Chicago in 1959. On the night he transferred his files from the old office to his new firm, my father put me into our 1955 Chevy, the first car he ever bought, and brought me along for the ride and the opening of his new law firm.

Soon thereafter, he designated me as the Clerk for his law firm, and promptly put me to work at the age of nine running messages, filing documents in court, taking money to and from the LaSalle National Bank, etc. all over downtown Chicago on school holidays and during summer vacations. It was not easy being the oldest child and namesake of a World War II US Marine Corps combat veteran of invading Saipan, Tinian, and Okinawa.

I continued to serve as his Clerk until he died of a heart attack on 10 January 1968 at the age of 46. Because I worked for him at his law firm for all those years, I was fortunate to have spent an enormous amount of time with my father. I learned a lot about life from my father. Two of his favorites were: "Son, there is nothing fair about life." And: "Just remember, son, no one owes you anything." Of course he proved right on both counts-and many others as well.

At first glance it appeared that my father had survived the war relatively unscathed. He had picked up a fungus on his leg that stayed with him for the rest of his life, which he called his "jungle rot." Also, his hearing had been impaired by the big naval guns bombarding the coasts while he and his comrades waited on ship to board the landing transports in order to storm the beaches, as well as by artillery, grenades, bombs, machine guns, flame throwers, and other ordnance that he endured, advancing under withering enemy fire during the day, repulsing bonzai charges at night, repeatedly volunteering for what looked like suicide missions behind enemy lines, etc. It was Hell on Earth.

Only years later, long after he had died, and as a result of medical research on veterans of the Vietnam War, did I realize that my father came back with a severe case of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), something that was undiagnosed at the time. Combat veterans of World War II were simply expected to go home and resume their civilian lives without further adieu. As my father's Marine Corps Honorable Discharge papers state: "Requires neither treatment nor hospitalization." In retrospect, my father should have had medical treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder if it had been available then.

My father never told anyone in our family that he had been at Nagasaki. Perhaps he did not want to recount the human horrors he had seen there to his wife and eight children. In fact, my father told my mother almost nothing about the war — unlike me, his oldest child and namesake. But he never uttered even one word about Nagasaki to me. He might have concluded that Nagasaki was nothing for America to be proud of — unlike the evident pride he displayed when recounting his numerous war stories to me. There was no war story about Nagasaki. Just a deafening silence.

In any event, I grew up to believe that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had saved my father's life and thus had made my life possible. Curiously, my father never told me that Hiroshima and Nagasaki had saved his life. Another Deafening Silence. I just bought into this commonly accepted myth while growing up in post-World War II America.

But when I later studied international relations in college with the late, great Hans Morgenthau starting in January of 1970, I gradually came to realize that the standard narrative of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ending the war against Japan in order to avoid an invasion was elaborately constructed, self-justifying government propaganda from the get-go. The Japanese government was desperately trying to surrender. The Truman administration knew full well that Japan would have surrendered (1) without the need to demolish Hiroshima and Nagasaki together with their inhabitants and (2) without the invasion of Mainland Japan by my father and his comrades-in-arms. The Truman administration dropped these two atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and their inhabitants in order to make it crystal clear to the Soviet Union and everyone else around the globe that the United States of America would be in charge of running the World in the post-World War II era. So it has been until today. 67 years of Pax Americana.

I doubt very seriously that is what my father was fighting for at Saipan, Tinian, and Okinawa. R.I.P.

Francis Boyle is a professor of international law at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.