|

"Another Brother" on Rikers IslandBy Elena Schwolsky-Fitch"My name is Clarence Fitch. I was born in Harlem, Harlem New York. My parents came to New York City from the South after the War. They were working-class people. My father was an auto mechanic. My mother was a telephone operator." The gravelly voice of my husband Clarence fills the classroom. The dim light from the TV screen flickers across the faces of the young men gathered to watch the video documentary, "Another Brother." Chairs scrape across the tile floor as kids fidget in their seats. A few murmured comments, a nervous laugh and then Clarence's voice again: "I was eighteen years old, right out of high school. I wanted to get away from the authority of my parents. I believed in the so-called ideals that may or may not exist. I believed the whole spiel - I went for it hook, line and sinker. I enlisted in the Marines right out of high school." The image of Clarence's youthful face, smiling in a graduation cap and gown, then stiffly serious in his Marine Corps uniform comes up on the small screen. The classroom is quiet now. The kids sink deeper into their chairs. The murmurs and laughter have stopped.

A teacher at Horizon invited us to show the film to his class. He supplied us with detailed directions, but the entrance to Rikers Island is hard to find and we make several wrong turns before we find the road leading to the jail tucked into a residential neighborhood in Queens. A bridge with a guardhouse divides the island from the community. Armed guards in full battle gear wave us along as we drive through the entrance. We have been warned that security has been tightened here, as in many locations, due to the "terrorist" activity in the Middle East, but the sight of semi-automatic weapons pointed directly at our car as we pass is chilling. A large sign across the entrance proclaims the Rikers Island corrections officers to be "the boldest in the world." It feels to me like we are entering enemy territory and voluntarily placing ourselves in the hands of these bold correction officers. Though they undoubtedly see our white faces and assume that we are on their side in the war on crime, I keep thinking that they can see right through me to the radical activist of the 60s who shouted "Down with the pigs" at anti-war demonstrations on the streets of Berkeley. Or that they know I am carrying Clarence's story on video with me in my backpack. How would they react if he were presenting himself? I remember one Sunday afternoon when he burst into our apartment shaking with fear and rage. The cops had noticed him cleaning out his car on a side street of our quiet suburban neighborhood and had frisked him at gunpoint because he looked "suspicious." As we hand over our papers at a series of ID checkpoints, my anxiety intensifies. Finally, we are issued a plastic chip that allows us to move through a turnstile to a waiting bus that will transport us to the detention center. As the doors shut behind us, I have a fleeting fantasy that all of my past transgressions against the law will be discovered and I will not be allowed out. The detention center is a large, square, nondescript building that houses the adolescent population at Rikers. We have been told to call Marty, the teacher at Horizon, when we arrive so we can be escorted to the school. A sign at the checkpoint here warns us: No firearms can be loaded in this area. We are informed that an "alarm" is in progress so we should sit down to wait. After about fifteen minutes, Marty appears to claim us, and we are ushered through an automatic metal door that clangs noisily behind us, and into the halls of Horizon High School. Horizon is a Board of Education-sponsored program that has been at Rikers for almost three years, explains our host. It was set up as the result of a class action lawsuit filed by the Legal Aid Society in 1996 against the New York City Board of Education and the Department of Corrections, which claimed that the lack of schooling at Rikers for 18- to 21-year-old prisoners violated state and federal laws. Horizon serves a constantly-changing population of young men, mostly in their late teens, who are being detained at Rikers while awaiting trial. Marty explains that these kids can be here for anywhere from a few days to two years. Attending school is not mandatory at Rikers, but it's just about the only activity allowed. Nearly one third of all Rikers inmates read below the 5th grade level, so there's a great need for education programs. Last year at Horizon, seventy-nine kids earned their GEDs out of the two thousand students then enrolled. But success is hard to measure in this environment, where a student may be working on a project in the computer lab one day and the next day be sent upstate to serve 25 to life. Marty focuses on the success stories - a few students actually passed their state Regents Exams, and one student recently wrote him to celebrate his enrollment in a college program. The smell of strong disinfectant is overpowering as we move through the narrow hallway toward the desk where we will show our IDs one more time. Guards move around the hallways, and classes shut down completely whenever an alarm is sounded. But the teachers make every effort to create a real school environment. As the kids are getting ready for a lunch break, Marty shows us around. Bulletin boards proclaiming "Hispanic Awareness Month" line one wall, containing photos of Ricky Martin, Jennifer Lopez, Tito Puente and Rita Moreno. Another bulletin board honors "students of the month." Three names are posted. Tami and I wander in and out of several classrooms where small groups of kids are working. We are introduced as "the producer and the star" of "Another Brother." The kids look very young to me. They are mostly black, a few Latino. Tami and I and the teacher have the only white faces in the room. We engage in some light banter with the group for a few minutes and explain why we are there and what "Another Brother" is about. "I wanna make a movie," declares a tall, light-skinned boy. "Can you help me? It's gonna be called 'Gangsta Vampires of the Lower East Side'." Tami explains that "Another Brother" is not a Hollywood movie but a documentary about real people. We speak briefly about Clarence, the work he did, why we made the movie. I introduce myself as Clarence's widow, which causes some confusion in the group. "Clarence, he's black, right?" asks one young man sporting a jail-issue orange jumpsuit and a head full of elaborate twists. "Yes, he was black," I reply, and from the back a kid with a big grin offers: "Oh-oh. Jungle fever!" We all laugh, me a little nervously, and Tami nudges me. "Are you sure you're ready for this?" she asks. We wait through another half-hour's worth of head counts, escorted trips to the bathroom and one interruption by the head guard, who strides into the classroom and loudly and forcefully threatens to "haul every last one of you to the gymnasium and strip-search your asses." This comes in response to a rules infraction - a few of the kids brought food into the classroom. Finally, we are ready to show the video. For the next 50 minutes, Tami and I watch these twenty incarcerated young teens watching "Another Brother." Whispered cries of recognition greet the appearance of familiar New York City streets and the Colgate Clock Tower in Jersey City. There is warm laughter at the sight of Clarence's white-haired 70-year-old mother showing off the absence of stretch marks on her belly after giving birth to eight children. The room is hushed as the screen shows images of young men in Vietnam bandaged and grimacing with pain, dead bodies being dragged in from the field, a young American soldier holding a gun to the head of a blindfolded Vietnamese boy. "I saw guys get their heads blown off, get their testicles blown off. I never knew what dead people smelled like till then. When you lay down at night the emotions just flooded through you; and we were so young," begins Clarence, describing his experience in Vietnam at the age of 19. These kids are 17, 18, 19. Is jail their rite of passage to manhood, as Vietnam often was for the young poor and working-class men of my generation? Will they come out of it as traumatized and bruised as Clarence and so many others did from the war? The archival footage of tanks lumbering down riot-torn streets in Newark in 1967 and of combat-weary and wounded soldiers in Vietnam has cast a silent spell on this small classroom at Rikers Island. Other scenes bring verbal responses from the group as the film continues. Loud laughter greets the political cartoon image, taken from a GI resistance newsletter of the 60s, of a white Uncle Sam being wrung out and muzzled by a series of strong black hands. When I appear in the film, since I have prepared them ahead of time for the numerous hairstyles I wear through the years, there is finger pointing and a general gasp of recognition. They pick out Tami from an old family photo in a collage of stills. This is not a Hollywood movie. We are real people and we are standing before them in a classroom at Rikers Island. "I was in and out of rehabs, mental hospitals, methadone maintenance, the VA hospital; suicide would have been the easy way out for me. I couldn't live like I was living." This is how Clarence describes his difficult recovery from a thirteen-year heroin habit. Can these young men at Rikers Island imagine a time when their communities were not flooded with drugs? How many of them have fathers, uncles, mothers and brothers who have wrestled with the demons of drug addiction? I watch them watching Clarence. They seem to be hanging onto every word. The last segment of the film is always hard for me to watch, though in many ways it represents the heart of Clarence's message. As Clarence describes in a matter-of-fact way his first battle with AIDS when he came so close to dying without saying goodbye, I am transported back to the intense pain of that moment. But Clarence survived that first round and lived his life to the fullest for the next two years - working for peace, reaching out to young people, celebrating small victories. "I've been pretty lucky, I guess," Clarence says in a quiet voice as the film ends. "I have no regrets. Nothing more to say, man. The struggle continues." And then it is over and we stand before the class and ask for questions. I invite them to ask me anything, even very personal questions. Somehow I want to be completely open to these young men, as if Clarence could materialize before them through my open heart. The first question nearly breaks my heart. "What do you think Clarence would be doing if he were alive today?" asks a young man on my right. Without hesitation, my response: "He'd be here talking to you, educating you, trying to give you some options and some tools to make choices in your lives." From the back, the boy who offered "jungle fever" is quiet and serious now. "How did you feel when you found out about his HIV? And how did his family deal with you?" I talk honestly and painfully about those first moments after Clarence's diagnosis: pulling the family together, not knowing if he would live or die. And about being an interracial couple in the 80s: the lack of acceptance by my family, the assumption on the part of the hospital that I was Clarence's "social worker," not his wife, when I brought him to the ER. More questions fly around the room. "Why did you decide to make this movie?" someone asks Tami: it's the "Vampire Gangstas" aspiring screenwriter really wanting to understand. When the questions have died down and it is time to go, I ask them to do one thing for us: to write down their impressions, how "Another Brother" affected them, and send them to us. "Uncensored?" they want to know. "The real deal?" asks one. A show of hands commits five or six in the group to write. "Will you write us back?" a small, sweet-faced boy in the back asks. We will, we promise. What will become of these young men, so expendable and cast aside? We know nothing about what brought them to Rikers and have not asked. We have shown them a film and shared a piece of our hearts, and they have reciprocated by taking our effort seriously and opening up a little to us. I am moved beyond words by this encounter. Tears are caught at the back of my throat but cannot be shed in this place. They will come later. The teachers are effusive in their thanks as we prepare to leave. "So many people promise to come, but they never show up in the end," reports one. "Too much of a hassle, I guess." As we are packing up to leave, a tall young Puerto Rican kid, who kept getting yanked out by the guards during the film showing, approaches us in the hall. "I'm a poet," he informs us, and we invite him to share one of his poems with us. He reads from a speckled black-and-white school composition book. The poem is gritty but full of hope and determination - he uses words well. "Keep writing!" I tell him. "Write it all down, everything." As we turn to leave, he touches his heart. "My mom's HIV-positive," he says quietly. "That movie really got to me." We have been inspired by this encounter with the staff and kids of Horizon High School. Marty, the teacher who invited us, wants us to come once a month to show the film and develop some learning activities with the kids related to the issues it raises - the war, racism, drugs, recovery. Clarence would have showed up. We will bring him with us.

Produced and directed by Tami Gold

|

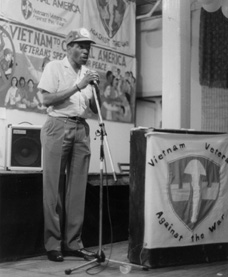

"Another Brother" is a documentary film about the life of my husband, Clarence Fitch. Clarence was an African American Vietnam veteran and anti-war activist, a recovering drug addict who died of AIDS in 1990. He spent the last few years of his life telling his story to black and Latino kids from poor neighborhoods - in schools, drug treatment programs, youth groups, wherever he could find them - hoping that they would learn something useful from his experience. Making "Another Brother" was our way of continuing Clarence's work. The documentary was shown on PBS in 65 cities during Black History Month when it debuted in 1997 and has won awards at several international film festivals. Now we are working hard to get it into the hands of substance abuse counselors, community organizations and veterans' groups. But above all, we want young people to see it - the young people that Clarence was trying to reach. Tami Gold (the film's producer) and I have shown "Another Brother" at high schools all over New York and New Jersey. Today we are at Horizon High School. Horizon is on Rikers Island and the students who are watching Clarence speak are detainees in the adolescent detention center located there. This is the first time we have shown the film to kids in jail.

"Another Brother" is a documentary film about the life of my husband, Clarence Fitch. Clarence was an African American Vietnam veteran and anti-war activist, a recovering drug addict who died of AIDS in 1990. He spent the last few years of his life telling his story to black and Latino kids from poor neighborhoods - in schools, drug treatment programs, youth groups, wherever he could find them - hoping that they would learn something useful from his experience. Making "Another Brother" was our way of continuing Clarence's work. The documentary was shown on PBS in 65 cities during Black History Month when it debuted in 1997 and has won awards at several international film festivals. Now we are working hard to get it into the hands of substance abuse counselors, community organizations and veterans' groups. But above all, we want young people to see it - the young people that Clarence was trying to reach. Tami Gold (the film's producer) and I have shown "Another Brother" at high schools all over New York and New Jersey. Today we are at Horizon High School. Horizon is on Rikers Island and the students who are watching Clarence speak are detainees in the adolescent detention center located there. This is the first time we have shown the film to kids in jail.