|

Flyboys: A Book and its CoversBy Dave Collins (reviewer)

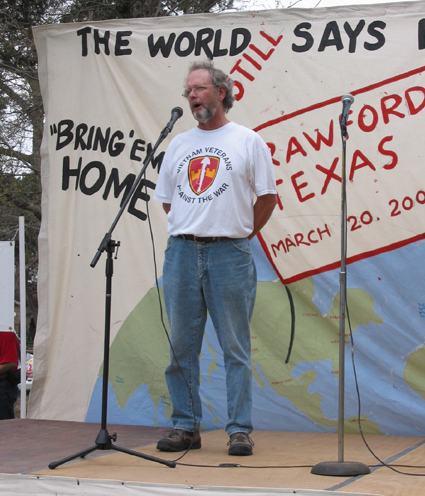

Flyboys: A True Story of Courage "Can't judge a book by lookin' at its cover," sang The Yardbirds. I have found few books of which this is more true that James Bradley's Flyboys. On the surface this appears to be yet another tale of the war in the Pacific. I undertook to read the book at the urging of a friend, but suspected I would put it aside after not too many pages. In Bradley's first World War II novel, Flags of our Fathers he tells the stories of the Marines on Iwo Jima. The central story of Flyboys is the fate of a group of Naval and Marine aviators shot down in raids against the island of Chichi Jima. However, after introducing this story Bradley engages in a lengthy digression. He sets about exploring the historical context for the Japanese aggression that began against the Russians in 1904, expanded against China in the 30's, and finally came to the US. Bradley argues that after Commodore Perry's gun ships opened Japan in 1853, Japanese leaders looked to western nations, the US in particular, as models for their imperialist period. Bradley undertakes an unflinching look at US imperialism in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He examines the long-running wars with nations of the indigenous peoples of North America, the invasion of Mexico in 1846, and finally the explicit imperialism of the Spanish-American War. Bradley argues that the first stage of Japanese imperialism, a highly successful expansion into Russian territories, reflected long standing military traditions of the samurai class. He suggests that the standards of conduct in that imperial war reflected samurai traditions of the honorable warrior. With a new, weak, emperor in 1926, the military began to change. Rapidly, Japan became a very different place, deeply militaristic from top to bottom. Bradley examines how the military even reached into the elementary schools, dictating curriculum. By the 1937 invasion of China, Bradley reports that perversion of the samurai tradition was complete. Military leadership was marked not by the broad, "liberal" education of the samurai but a narrow and constrained base of knowledge intended to produce a ruthless and racist killer. Junior troops were treated as near slaves trained to accept brutality from their superiors as the natural order. All civilian efforts turned to the waging of wars of conquest. Only with this context established does Bradley return to the central story, the lives and fate of a handful of aviators taken prisoner by the Japanese garrison on Chichi Jima. Here Bradley shapes the story in the tradition of "honoring the warrior, not the war." He traces the story of each man from childhood to death at the hands of their captors. The tale of each man is told through first person reports of surviving family members, friends and comrades. The only one of these fliers to have survived, G.H.W. Bush, receives no special treatment due to his subsequent celebrity; an admirable bit of restraint on the part of the author. In telling of the suffering the captives endured, Bradley again provides context, returning to the "Indian Wars" and the US occupation of the Philippines. In this well-documented section of the narrative he examines the great grandfather of "waterboarding" developed by the Army in the Philippines and encouraged by US military leadership. He also documents the brutality of the Japanese in the China campaigns, where the senior officers on Chichi Jima honed their brutal ways. The most chilling aspect of this part of the tale relates to ritual cannibalism that arose among Japanese officers in Malaysian campaigns and brought to the little hunk of rock in the North Pacific. In examining the conclusion of the war, Bradley's writing gives the appearance of becoming confused and unfocused. Discussing the pending invasion of Japan, he at one point takes the side of the debate that says invasion would have been monumentally costly, that each and every Japanese civilian would have taken up whatever arms were available to repel the invaders. Noting the deep penetration of military propaganda and its effects on the psyche of the population, he poses the argument that the cost in US military casualities might have run to the millions. He then flips the argument as he examines Curtis LeMay's firebombing campaign and its devastating consequences in most major cities of Japan. Replete with interviews of survivors of the firebombing of Tokyo and other cities, he makes real for the reader the horror that campaign produced and the devastation it wrought. In one startling passage, he presents data compiled by the Strategic Bombing Survey reflecting the extent of damage – in one city fire destroyed over 80% of the residences. So, when Bradley finally comes to the flight of the Enola Gay, it is simply impossible for this reader to determine his perspective regarding employment of nuclear weapons to end the war without invasion. It seems that it is likely that Bradley sought to convey the confusion and uncertainty that may have been quite real for decision makers at the time. He does note that the destruction and death resulting from firebombing overshadowed that of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by orders of magnitude. Though based on the cover of this book I would not have guessed it, James Bradley has made a significant contribution to the annals of anti-war writing. Flyboys is a unique addition to that canon and worthy of a serious read. Dave Collins is the Austin contact for Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Following his retirement from a career as a management consultant, he returned to peace and justice activism, an effort he began in 1971 as Oklahoma coordinator for VVAW. He has helped Non-Military Options for Youth in Austin, working to ensure that young men and women consider the enticements of recruiters with all the facts. He has also worked with Veterans For Peace as a speaker and in support of the documentary Cost of War. He is a co-founder of OIF/OEF Veterans Assistance Fund.

|