|

The Machine Breaks DownBy Brian Gryzlak (reviewer)

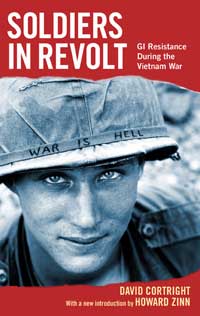

Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War

Discourse over the motivations for (and the state and trajectory of) the current war in Iraq is often imbued with comparisons to the Vietnam War. It is in this context that the new edition of David Cortright's Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War (first published in 1975) is an especially salient and timely read. With an introduction to the 2005 edition by historian Howard Zinn, Soldiers in Revolt chronicles acts of resistance within the US military to the Vietnam War and the conditions of military life. Cortright documents how resistance was most prominent among enlistees of working-class backgrounds, volunteers (as opposed to conscripts), and African Americans. GI resistance to the war (and various facets of military life) assumed many forms, ranging from conscious dress-code violations and attempts at unionization to circulating on-base petitions, disobeying orders, and committing direct assaults on officers. GIs spoke out against the institutional racism of the military and held rallies. With the support of civilians, they founded newspapers to disseminate information among the ranks and established off-base coffeehouses, which were venues for organizing efforts. As the war progressed, the military faced increasing desertions, AWOL soldiers, and conscientious objectors, and declining reenlistment rates, which initially hit the Army and Marine Corps hardest, as these branches faced the most direct combat exposure. As air assaults were stepped up in the early 1970s in place of ground forces, acts of resistance shifted from the Army and the Marine Corps to the Navy and the Air Force, and included sabotage of Navy ships, attempts to block ships from deploying to Vietnam from the United States, and on-ship sit-ins. With the end of the draft in 1973 and the subsequent drawdown of US forces in Indochina, GI organizing efforts shifted to improving day-to-day conditions of military life, focusing on challenging institutionalized racism and working toward the democratization of military life. Cortright also details the "recruitment racket" that ensued once the draft ended in 1973, illustrating the deceptive, pressure-laden tactics employed by military recruiters to sign up volunteers; those with limited prospects for social and economic advancement were prime targets for recruitment (often referred to now as the "poverty draft"). Cortright highlights the non-transferability of skills learned in certain roles to civilian labor markets and the discrepancy between the demand for transferable skill sets to the civilian labor market and the supply of such rarely needed skills; e.g., those of weapons mechanics. The global commitment of US military personnel drives the "recruitment racket" to staff an "all-volunteer" military, currently spread across over 700 bases throughout the world. Add to the mix the unemployment and underemployment endemic in the United States, and a recipe for channeling the economically disadvantaged into the ranks of the military emerges, enabling the country to continue its interventionist policies. In a postscript to the new edition, Cortright delves further into the extent of GI resistance during the Vietnam War; drawing from thirty years of evidence on the issue, he argues that GI resistance was much more pervasive than initially thought. Resistance among GIs stationed at bases in the United States and those stationed in Indochina (and simultaneous dissent at bases elsewhere throughout the globe) threw the status of the US military as a viable institution into question. Moreover, veterans played a critical role in stoking antiwar sentiment, and VVAW "convincingly demonstrated to the American people and US political leaders that the war had to end." In fact, the attorney general for the Nixon administration branded VVAW as "the single most dangerous group in the US," clear evidence of its effectiveness as an organization. Absent from current mainstream media assessments of the situation in Iraq are the substantial and growing contributions of US military personnel to the opposition to the war. In fact, as with veterans of the Vietnam War, Iraq war veterans and their families have established organizations aimed at bringing the troops home, including Military Families Speak Out, Iraq Veterans Against the War, and Gold Star Families for Peace. Soldiers in Revolt demonstrates how GI resistance disrupted the social order of the US military and effectively undermined its ability to function. While the mass protests and social upheavals of the US civilian populace played a critical role in influencing policy, the acts of GI resistance were an enormously important factor in the withdrawal of US forces from Vietnam. Three decades later, it is clear that Soldiers in Revolt can be read not only as a fascinating and detailed history of mobilized discontent among GIs during the Vietnam War, but also as a resource for the current antiwar movement. Brian Gryzlak lives in Tiffin, Iowa and is a member of the University of Iowa Antiwar Committee and a former member of the Progressive Resource/Action Cooperative (PRC) in Champaign, Illinois.

|