|

My 1968: Exodus and Re-entryBy Joe MillerAfter six years and ten months on active duty, I was discharged from the Navy on February 3, 1968. I was excited and apprehensive about this drastic, but welcome, change.

Two years earlier, I arrived at my final duty station, Helicopter Training Squadron Eight, at Ellyson Field, near Pensacola, Florida. Being there was made more palatable by the fact that my wife and daughter were with me, and we knew that I was getting out in two years. I was assigned to the Executive Officer's Administration Office. I was the only military person in that office; the rest of my office mates were career civil servants. This base produced Navy and Marine helicopter pilots, a good number of whom went off to war in Vietnam. Most of the instructors already had flying experience in and around Vietnam, so we often heard their war stories. Since I turned against the war back in 1965, I was not impressed by any of this. I was more concerned about the "whys" of war, racism, poverty, and dissent. I did not want to hear any more about how many had been killed, who won what medal and why. How many would be left alive, on all sides? In January 1967 I was advanced to Yeoman Second Class (E-5). I was being pressured to re-enlist. It was like, "Gee, Joe, you only need to put in thirteen more years and you can retire at age 38." I teased one of the retention non-coms when I said I might consider this IF I could be sent back to Taiwan with my family. He could not give me such a guarantee. End of discussion. In March, the local newspaper, the Pensacola News-Journal, slammed Senator Robert F. Kennedy for his recent critical stance on the Vietnam War. Though I had discussed the war with shipmates and in letters home while in the war zone, I never made any real overt public statement. It was time to speak out. However, I did not identify myself as an active duty sailor. This first public expression of opposition to the war was in a "Letter to the Editor," published on March 19, 1967, under the title "Freedoms Questioned." The title was assigned by the editors. I took the newspaper to task, point by point. What "freedoms" were we defending in Vietnam? What was the real history of our involvement there? I defended Kennedy's willingness, as an early supporter of the war, to finally admit that the US had been wrong for twenty years! Since it was the paper's policy to print the complete address of any letter writer, I received some hate mail from local "patriots" in this military town. The letter, along with anti-war remarks to colleagues at an off-duty part-time job at a local department store, brought me to the attention of the local FBI office and the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI). A fellow worker at the store, a Marine Corporal stationed in Pensacola, told me that investigators visited the store when I was off and questioned everyone about me and my political statements. Soon after this, my boss called me into his office and said he had to let me go...without any explanation. I knew why. I joined the local chapter of the ACLU, just in case. In mid-May, I was due for a military performance evaluation. These evaluations took place every six months, and they were written by one's immediate supervisor, in my case a Yeoman First Class (E-6) who was the admin assistant to the Executive Officer. According to my civilian supervisor, this guy often visited my office while I was at lunch to take note of the titles of books on my desk. Here is what he wrote and placed in my service record: "Petty Officer MILLER is very capable of performing any duties assigned. However, his lack of initiative in performing his military duties and his overt interests in non-military activities is very obvious. He spends all his spare time reading books and publications concerning current world situations, thus devoting only the very minimum of his daily schedule to his professional duties. His military behavior leaves very little to be desired as he constantly acts in the highest traditions of the naval service. His leadership and supervisory ability suffer from his lack of interest in his professional duties. His military appearance is always exemplary. Petty Officer MILLER has a very highly 'self-centered' personality and rarely assumes any role other than 'speak only when spoken to.' Petty Officer MILLER has an excellent command of the usage of the English language both orally and written." [from "Report of Enlisted Performance Evaluation" NAVPERS 792. Dated: 16 May 1967] Apparently, as a Navy man, I was not supposed to care about "current world situations," even in my "spare time." In my mind, I was already a civilian, just wearing the uniform and going through the motions until the date of my discharge, now less than a year away. I had already taken the ACT in preparation for entrance into college. The re-enlistment counselors no longer bothered to contact me. I was known to be "lost."

This transformation, this exodus from 'soldier' (sailor) to 'citizen' status was certainly gradual, but now it was real and final. I happily signed my discharge papers on February 3, 1968, reentering the civilian world, a world that was much different, as I was, from when I first enlisted in 1961. Weeks before, the spy ship USS Pueblo had been seized by North Korea. In Vietnam, the Tet Offensive began on January 31st. This was the international context in which my family and I left the Navy and got on the train from Florida to Chicago. My folks gave us living space until we could get on our feet. Now I had to find a real job in the real world. Since my dad still worked at the Western Electric Hawthorne Plant in Cicero, I figured I would start there. I needed something while I was attending college. I went to the plant, filled in the job application, and was given a physical. In the end, they denied me a job, claiming there was something wrong with my back. How did the Navy miss this, I wondered? Was this real? I had to find something for us to live on, since the GI Bill alone would not support the family while I was in school. One day, I just went into the Loop and walked into the Sun-Times/Daily News building [located where Trump Tower now stands]. In less than an hour I got a full time job, an overnight shift so I could take classes each day. I was assigned to the communications center of the Daily News editorial department. Basically, I was responsible for clearing and maintaining the teletype machines that sent news items to the paper, as well as bringing printed column proofs to the editorial staff. As for college, I enrolled for the spring quarter at the University of Illinois Chicago campus (mainly called Circle Campus). All students were commuters, since there was no student housing back then. I had never enrolled in college before, but I obtained 72 credit hours from my military service (60 hours came from my Chinese language training). Though that meant I would only need three years to graduate, I still had to take all the basic general education courses, like science and rhetoric. That first quarter was a little rough; I had not been in civilian school for eight years. For a commuter campus, there was a high degree of political activity at Circle. The level of anti-war activity was pretty high. When McCarthy managed to make a significant showing against Johnson on March 12th, the number of his supporters grew. Celebrities like Paul Newman and Sammy Davis Junior spoke on campus during this period. Once Bobby Kennedy jumped into the race on March 16th, that brought even more students into the electoral campaigns. Outside of electoral issues, there was a strong chapter of the Young Socialist Alliance (YSA) on campus, arguing for immediate and unconditional withdrawal of US forces from Vietnam. All this activity swirled around students who just wanted to go to class. And the war just went on; the bloodletting increased. I was mainly an observer, surely anti-war, but hesitant to join any organization after nearly seven years in the military. Also, I did not highlight my status as a veteran, even though I was awarded the Vietnam Service medal. Since I had never been in combat, I did not feel like a legitimate veteran at that time. In fact, few outside my family and close friends even knew that I had been in the military. I was just another student, working a full-time job, attending classes, and showing up for any anti-war activity that popped up on campus. To be sure, I can't recall anyone on campus in early 1968 who identified as a veteran, let alone a veteran of the Vietnam war.

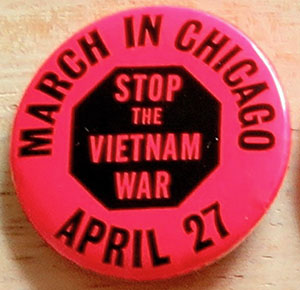

Things changed dramatically as March flowed into early April. On Sunday afternoon, March 31st, my wife and I joined friends to attend a performance of Barbara Garson's antiwar/anti-LBJ play "MacBird". Later that evening, as I was getting ready for work, my family and I watched as LBJ announced he would not be in the running for president. Wow! What next, I thought? Then, four days later, the next shock to the system. On the evening of April 4th, I awoke to the news that Martin Luther King, Jr. had been murdered. Holy crap! What's going on? As I rode the bus to work and got closer to the city, we passed burning structures here and there. These were symbols of local anger and frustration over King's assassination. By the time I arrived at work, the newsroom was in complete chaos as reporters and editors tried to keep up with the volatile situation. Mayor Daley had put out his "shoot to kill" order to the Chicago cops, loosening any possible restraint on their actions. Next morning, I left work and took the subway over to Circle for class. The campus and the immediate neighborhood was in shock. There were no classes that day. Black students and local residents blocked Halsted Street for hours. I went home to watch the news reports about this national urban uprising; even Washington, DC was in flames. Why were so many surprised? Three weeks later, on April 27th, the Chicago Peace Council sponsored a rally and march in opposition to the Vietnam War. This was coordinated with similar events in other cities. My wife Linda and I decided to attend this event, our first public activity against the war since my discharge. We were clueless as to how these things were organized. We just showed up at Grant Park. I was given a small sign to carry, "Support our GI's! Bring them home now!" We tried to listen to the speeches, but the sound system sucked. So, we just waited for the march to begin. A number of people wore military-style caps that identified them as "Veterans for Peace in Vietnam". These were not Vietnam veterans, as far as I could tell, but more likely World War II and Korea veterans. So, we waited for the march to begin. We were completely new to all this; we had no idea that there had been a struggle with the City for rally and parade permits. The march began, but we were moving very slowly. Later reports stated that there were nearly 7,000 people there. We would move perhaps a block, then be stopped for a long time. Finally, being the neophytes we were, Linda and I just decided to "jump the line." We worked our way into the Loop on side streets, eventually getting near Civic Center Plaza (renamed DuSable plaza by the demonstrators). The crowd was enormous, so we were stuck out on the edges. We could hear shouts and screams echoing from the plaza. We had no idea what was actually happening. We would find out later in the news that the police had attacked the crowd. We were probably lucky not to be near the front. Welcome home, Joe! Welcome back to "the world"! What would happen next in this tumultuous year? Joe Miller is a Navy veteran, 1961-68. Naval Security Group, 1961-64. USS Ticonderoga (CVA14), 1964-66. HELTRARON 8, 1966-68. He is a VVAW National Board Member.

|