|

Myth and MemoryBy Kim Scipes (reviewer)

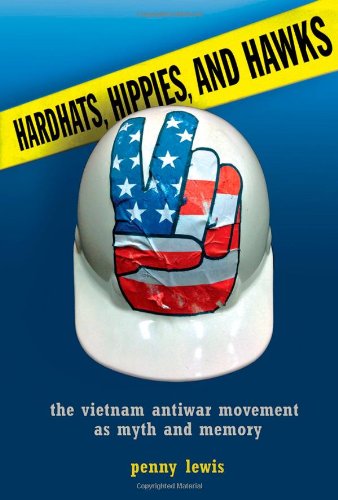

Hardhats, Hippies and Hawks: The Vietnam Anti-war Movement as Myth and Memory Penny Lewis has written an important book about the Vietnam anti-war movement, challenging important myths and received memories that have affected US politics ever since. The myth, on which much received wisdom is based, is that it was upper middle class folks and elites who opposed the war, while working class Americans supported it. The reality, she quotes from Howard Zinn, is that "throughout the Vietnam War, Americans with only a grade-school education were much stronger for withdrawal than Americans with a college education." Lewis spends considerable time supporting her argument. While she notes that initially the anti-war movement was populated and led mainly by activists from elite universities, this didn't last long. Many working class people joined the movement and eventually, the movement looked very much like the general population of the United States. She tries to understand this reality, and how it was misrepresented by the right (particularly by the Republican Party under Richard Nixon) and accepted by the mainstream media. Accordingly, the myth has been passed on as historically correct. Part of the difficulty of understanding this movement (she claims there are no full-length sociological studies of the anti-war movement) is its size and heterogeneity: "The Vietnam anti-war movement was a massive, sprawling, multiheaded phenomenon. It is estimated that as many as 6 million Americans actively participated in it in one form or the other, with another 25 million sympathizers." And it was "internally riven, with revolutionary nonreformers battling those who would work within the Democratic Party, proponents of a single-issue orientation fighting those who would broaden its objectives, and full of heated disagreements about demands, audience, and especially tactics." However, Lewis argues that the myth was built on an all too limited class analysis - limited to white workers only. She shows that when we consider workers of color, there actually was much more opposition to the war among them than among white workers. However, the concept of class, even among whites, was generally limited to the organized part of the working class, i.e., the labor movement. The leadership of the AFL-CIO solidly and resolutely supported the war: "The bulk of the labor movement, embodied in figures like George Meany, remained to the right of its members on issues of war and peace, and remained sclerotic and unyielding on the issue of rank-and-file democracy." Where Lewis really gets it right is when she recognizes the important role that ordinary soldiers (GIs) and veterans of all racial groupings had in ending the war. These people came overwhelmingly from working class homes, and while they recognized that, they didn't identify themselves on an explicitly class basis. Their actions, however, built an anti-war movement inside the US military that, over time, limited the US' ability to fight the war on the ground in Vietnam, in the air forces that were attacking from above, and on the ships offshore. [A plug here must go to David Zeiger's wonderful film on this, "Sir, No Sir!," with a truncated 48 minute version of the 84 minute film now free on YouTube. Highly recommended.] So, in other words, the conservatism of the working class was a misrepresentation of what was really going on. In fact, working class people both supported the war (as has been well reported), and opposed the war (as has been much less reported), but the latter has been purged from our memories and representations of the war. Lewis tries to understand where the myth came from; how could such ideas develop and get settled in our understandings of the war, despite being so wrong? She says we have to go back to the 1950s, and argues that the stories in the media during that period of the "affluent white working class" laid the groundwork for the "working class as conservative" trope of the 1960s to the early 1970s. Basically, she says that organized labor of this period had no major figures nationally who would stand up for them and their interests other than the arch-conservative, George Meany. This is the one place this reviewer disagrees with Lewis. The roots of the problem didn't emerge in the 1950s, but rather in the late 1940s. The supposedly radical Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) purged 11 left-wing unions from the labor center in 1949, a move that disemboweled the labor movement, and continues to affect organized labor today. These left-led unions were supposedly led by communists, but in reality included people of a wide range of politics, including communists, socialists, anarchists, former members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), black nationalists, rank and file militants. They were people who were willing to "think outside of the box," and who had the audacity and willingness to utilize direct action in the workplaces to get what working people needed. [According to Steve Rosswurm, as the CIO expelled somewhere between 750,000 to a million members with these unions, the FBI later stated only 16,520 trade unionists, less than 1 percent of the total CIO membership, had been members of the Communist Party.] By removing the left from the labor movement, the wider social justice concept of labor became confined to just narrow business unionism. Without having these broader values and goals as essential parts of the labor movement, there was basically no one who could challenge the conservative leadership of people like Meany, who claimed to represent all working people. Lewis' argument would have been even stronger had she made this connection. Nonetheless, this is an excellent study of the Vietnam anti-war movement, which she uses to try to think about politics today. Labor's position concerning the Occupy Wall Street Movement, for example, has been considerably different than it had been to the war in Vietnam. She makes a strong case for treating working people with respect, and not just accepting old myths that were false even when they were new. Kim Scipes, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Purdue University North Central in Westville, Indiana. The Chair of the Chicago Chapter of the National Writers Union, UAW #1981, he served in the US Marine Corps from 1969-73, where he got politicized fighting white supremacy and racism, while staying in the US all four years.

|