|

Black Political Prisoner: Nam Vet Deserves FreedomBy Ben ChittySome stories show with such clarity how deeply our society buries its wrongs that you have to wonder if the people responsible are as crazy as they are evil. Consider the case of Elmer Pratt, serving a life sentence for the December 1968 murder of 27-year-old schoolteacher Caroline Olsen during an $18 robbery on a tennis court in Santa Monica, California. Arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department in 1970, Pratt was convicted in 1972 on an identification by an eyewitness (the victim's husband, wounded in the attack), and on the testimony of a man to whom Pratt had admitted the crime. What's wrong with this picture? The victim's husband first described a much larger man, then identified someone other than Pratt as the assailant, then identified still another suspect, and then still one more, before finally identifying Pratt at the trial. The witness who related Pratt's admission was a police informant. A second police informant (not yet identified) was on Pratt's defense team. And, on the day of the murder, Pratt attended a meeting in Oakland, California, over 300 miles away - which was under FBI surveillance.

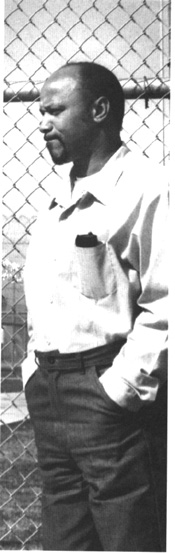

Elmer Pratt was born and raised in Louisiana, joined the Army, and served two years in Vietnam, receiving two Purple Hearts, cited twice for bravery. After his discharge in 1968, he enrolled at the University of California at Los Angeles. He also became active in the Black Panther Party, eventually becoming head of the LA chapter. One of his comrades was an older man named Julius Butler, an ex-deputy sheriff and chief of Panther security for southern California. Butler was a tough guy - a retired LAPD captain recalled that when the Panthers confronted the police, Butler always stood out from the rest in the obscenity of his language. Pratt grew to distrust Butler, and in August 1969, confronted, threatened, and expelled him from the Party. Too late: Butler had already become a police informant, perhaps even a provocateur, because (he told the FBI) he disagreed with the direction the Panthers had taken. Worse for Pratt, Butler took the precaution of depositing a sealed letter with one of his police controls, in which he claimed he had heard Pratt admit the Santa Monica murder. After a 1970 FBI Cointelpro review of the LA Panther situation, the letter was turned over to the LA District Attorney's office. At the trial, Butler denied he had any relationship with the police or the FBI. Pratt had an alibi - on the day of the murder he had attended a Panther meeting in Oakland. Pratt had already survived one Cointelpro action, a police assault on the LA Panther headquarters which he escaped because he had been sleeping on the floor to relieve the pain of a spinal injury from Vietnam. But now his luck ran out. Cointelpro had succeeded in provoking a split in the Party between Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver. Pratt had gone with the Cleaver faction, and by the time of his arrest had himself been expelled from the Party. Most of the other Panthers stayed with Newton's faction, and refused to corroborate Pratt's alibi - only Kathleen Cleaver testified on his behalf at the trial in 1972. (Unknown to Pratt, the FBI maintained wiretap surveillance of the Oakland meeting, and logged Pratt's presence before and after the murder. These logs - described by retired FBI agent Wesley Swearingen in depositions and publications - can no longer be located by the Bureau.) Pratt continued to maintain his innocence through four appeals and more than a dozen parole hearings. Olsen's identification was discredited in 1972. Butler's relationship with the police was disclosed in 1979. The FBI surveillance was described in 1985. Other ex-Panthers confirmed Pratt's alibi in 1992. The courts held that all these were "harmless errors" (despite affidavits to the contrary from three of the original jurors), not the new evidence that might force a new trial. California prison officials also tried to close the case. Pratt's prison records were altered to show he plotted to kill prison guards with poison darts, kidnap their children, and twice to escape. None of it was true - Pratt's good behavior had earned him family visits and outside work privileges - but the false reports earned him high-risk status and trigger-happy guards. From December 16 through January 10, Pratt's latest appeal was heard before Judge Everett Dickey in the Orange County Superior Court. Testimony focussed on the role of Julius Butler, and uncovered a history of his cooperation with the LAPD, the LA District Attorney, and the FBI (including his "confidential informant" cards in an LAPD file) which surprised even Pratt's lawyers. Commenting on the contradictions between Butler's testimony and other evidence, Judge Dickey said "It's always unfortunate when the Court has to reach the conclusion that somebody is deliberately lying on the witness stand." Butler himself at one point had to acknowledge on the stand that he could understand why people might think he had been a police informant (though he continues to deny being a "snitch"). Written arguments have been submitted, oral arguments follow at the end of February, and a decision can expected by late March or April. News coverage of the appeal has provided glimpses of some of the participants twenty-five years after the 1972 conviction. Caroline Olsen's husband is dead, as are Larry Hotter and Herbert Swilly, the two friends of Julius Butler who may have committed the murder. Butler himself - after arranging with the DA to reduce some felony convictions to misdemeanors - became a lawyer, and now serves as chairman of the board at Los Angeles First African Methodist Episcopal Church. Richard Kalustian, the district attorney who directed the original charade, is now a Superior Court judge in Los Angeles County. Johnnie Cochran remains Pratt's lead lawyer. Jeane Hamilton, one of the original jurors, is now a schoolteacher. She attended every day of the Orange County hearing. In her opinion, "We were victims. We were pawns of the government. We were set up. It's so difficult to put into words. It's such an injustice." Pretty good words. But the last word belongs to Elmer Pratt, now known as Geronimo ji-Jaga. In a letter to long-time friend Mohammed Mubarak the day after the new hearing started, he wrote: "My interest was, is always not merely to clear my name, but more importantly to clear our movement of such vile obliquity." Nice word, obliquity. It means "divergence from moral conduct, moral delinquency, mental perversity." And describes exactly what keeps Geronimo Pratt behind bars. For more information, contact Geronimo Pratt Defense, PO Box 781328, Los Angeles, california 90016 (213-294-8320). Ben Chitty is the East Coast Coordinator of VVAW and a member of the Clarence Fitch Chapter. He lives in New York and works in the University Library at CUNY. He served in the US Navy 1965-69, Vietnam 1966-7, 1968.

|

But 26 years after his arrest, Elmer Pratt remains in prison. Tracing how this happened illuminates some of the hidden history of the Vietnam experience and its toxic legacy

But 26 years after his arrest, Elmer Pratt remains in prison. Tracing how this happened illuminates some of the hidden history of the Vietnam experience and its toxic legacy