|

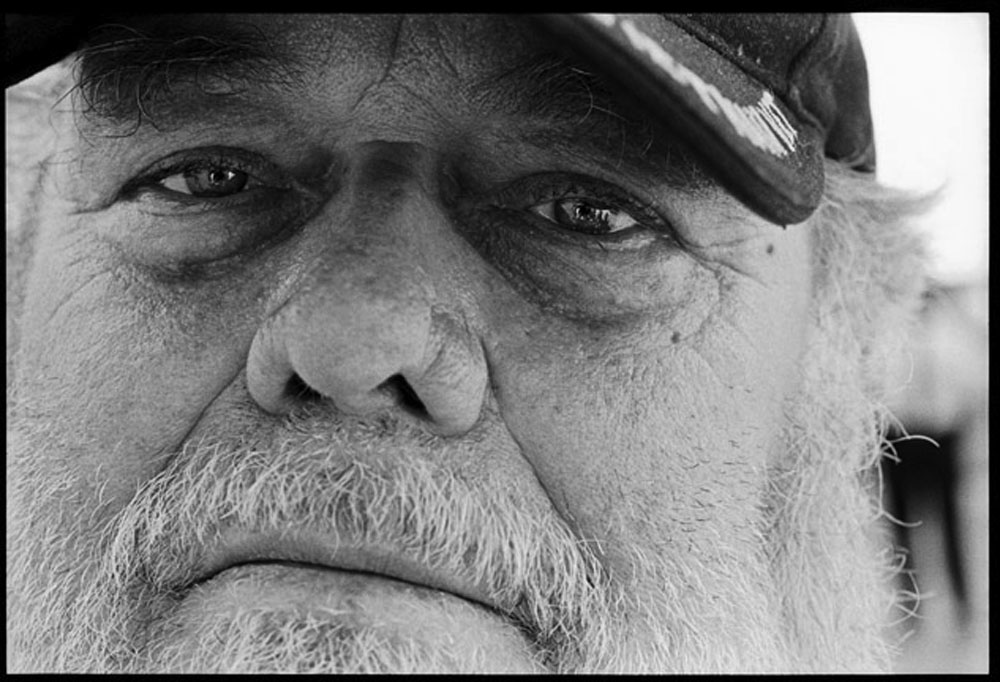

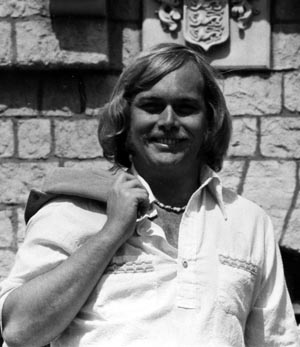

John Piester - An Unsung HeroBy Cindy PiesterJohn Piester was one of VVAW's unsung heroes. His life was defined not only by his war experience in Vietnam during 1966 and 1967, but how he used it to help others.

John was 19 when he was drafted into the Army, and joined the Navy instead. He was sent to Camp Pendelton Survival Training in preparation to serve as a Riverine. His job with the Brown Water Navy was to man the 50 caliber machine gun while patrolling the Mekong Delta in small agile PBR (patrol boats river). Their mission, called Operation Market Time, included boarding small Vietnamese junks to stop the flow of weapons from the north into South Vietnam. Often fired on from the banks, the River Rat, as they were sometimes called, constantly faced ambushes and uncertainty. Even so, John came to care for the Vietnamese people. He and his buddies sometimes helped the fishermen by tossing an occasional percussion grenade overboard allowing them to gather the fish that floated to the surface — a fond memory. Unfortunately, not all of John's memories were so fond. Shortly after arriving in Vietnam, he came to the conclusion that Vietnam was a very wrong war. The Riverines frequently delivered Marines up river. John was upset with the whole Search and Destroy way of conducting the war. He told the story repeatedly of how our soldiers were actually used as bait when they were sent out to be ambushed. He was in disbelief that soldiers were constantly being put in the position to call in heavy artillery strikes on their own coordinates because they were being overrun by the waiting North Vietnamese forces. While this resulted in high body counts for the enemy, it also cost the lives of many of our men. He talked about officers giving insane orders and putting their own men at risk in order to earn medals and go up the chain of command. John did not appreciate that he and the others were eating C-rats left over from WW ll. Likewise, he thought it was wrong that their supplies, sometimes even their ammunition, had been left over from WW ll and didn't always work. He talked about one incident, in particular, that totally horrified him. He and his buddies were out on patrol and ordered to fire on the shore. Afterwards, they had all gone ashore to check on damage. The vision of what he saw there changed his life forever. He never got over it. Never. He knew that chances were that his own bullets had been among those that struck and killed innocents and he could not forgive himself. He felt our government had put him in that position, but he had to live with the reality of it. If he survived the war, John decided, he would help children when he got back to the states.

Agent Orange was everywhere. He saw the guys cook their own food atop barrels of the stuff. He was constantly sprayed. They had been reassured it was safe. In 1966, John was part of a mission that delivered Marines into Cambodia. He didn't know why or what they were doing there, only that this was happening. He wrote to his father about this only to find, on return, that his letters to his father had been intercepted and all mention of Cambodia had been cut out. He was blown away that the American people were being mislead and lied to by their own government. While in Nam, he got his "Dear John" from his sweetheart. He was devastated. His letters home to the parents were reassuring. He never wanted to worry them, but it was all insane. Nothing made any sense. Thankfully, he survived. When his C-130 finally delivered him home safely, he kissed the ground. He was so so glad to be back. His family was overwhelmed with joy to see him, but he skipped out on the party they had happily planned. Instead he got drunk with another veteran's family and unloaded some of his grief about the war. His life had changed forever and John was no longer the life of the party that he had been. Days later, he was embarrassed during a blind date when a car backfired and he found himself on the ground. Isolation would become a way of life for periods of time in the years ahead. John always felt that we had to support the troops even if the war, whatever war, was wrong. He would say, "You just don't know what it's like to come back after all we had been through!" He tried to return to classes but was called out as a "baby killer" by one professor. Things were not easy. He came home with nightmares and flash backs. Thoughts of suicide plagued him through out his life. The pineapple and sugar cane fields of Hawaii became a refuge as he got himself together. The best and most immediate thing he felt he could do was to became a member of VVAW. He wanted the war ended. He wanted his brothers home and safe. He spoke out against the war publicly, including giving a talk at San Fernando State College (now California State University, Northridge). Speaking out was not acceptable and the FBI showed up at his house. Nonetheless, John's life was committed. He would never back down. Neither, did John ever forgot the promise he had made himself in Vietnam to help children. He became a licensed psychiatric technician who helped countless emotionally disturbed children over a career that lasted more than two decades. His compassion and insight made him more of a stand-in dad than a staff member. He was proud of having started his career at UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute. Later he moved to northern California where he initiated the Community Re-Entry Program for emotionally disturbed teens at Napa State Hospital. Returning to southern California, John worked in what was probably the California State Hospital's most revolutionary treatment programs for boys, the Re-Ed Program. John's career came to a sad close when the hospital was shuttered. John and I had been friends for many years, but we were not able to marry until he went through his own extended therapy with the Vets Center in 1989. John found this group work highly beneficial and he did his best to encourage his veteran friends to go themselves. He was always deeply concerned about vet's issues. He knew those issues and he did all he could to help others. With the advent of the Iraq War, John was devastated to think of another generation having to experience war trauma. His own PTSD symptoms reemerged. He foresaw what was ahead for a new generation of soldiers and what was ahead for the people of Iraq. He was just sick. We both were. He foresaw the deaths, destruction, the suicides. For as long as John was able, he used his credibility as a combat vet to stand up for peace and justice and to call for an end to US wars of aggression. This was not always an easy road. Friends and family were not always open to hearing what John had to say, but he never wavered. He spoke boldly and with conviction to both strangers and friends. He wanted people to understand the realities of war. He was appalled by the glamorized Hollywood version of military engagement. John lived a simple life. His prize possessions were his VVAW sweatshirt and a couple of VVAW t-shirts and a couple of caps. He wanted the people of the country to pay attention to what was going on rather than immerse themselves in materialism. John began losing his health in 1997 and was forced into early retirement. He had developed peripheral neuropathy. He was diagnosed with colon cancer, hypertension, and later with congestive heart failure. All of these may have been related to his heavy Agent Orange exposure. He was also disabled from numerous injuries. John worked out intensely and religiously. His muscle tissue should have built, but it didn't. Agent Orange wastes muscle and, for all of John's effort, his muscles remained atrophied. He was reliant, first on a cane, and then, on a walker the rest of his life. He endured many illnesses and setbacks, yet he heroically pushed himself to get up again and again. He and I were certain that the years of pain, suffering, and endless trials were going to pay off and we would enjoy healthier years ahead. We were wrong and John's tragic death from a heart attack came unexpectedly last November. John did what he thought was his duty to his country only to come to the conclusion that the Vietnam War was dead wrong. He joined VVAW and remained loyal to the organization all of his life. He took great pride in the fact that his brothers-in-arms had come together to speak out and successfully end the war. He spent decades helping emotionally disabled children find their own inner strength so that they could grow up and live fuller lives. He faced countless challenges to his own health and well being, including severe PTSD and Agent Orange. He did it in a heroic fashion. His life was not easy and he would not want it white washed. Neither was it easy for me or our family, and I often failed, but I am honored to have been his wife. He was my partner and I will always love him and treasure the happiness he brought to my life. He is gone, but not forgotten. While it is terribly disheartening that our nation is in such terrible shape, it seems as though the best way we can honor John's life is to continue to confront the injustices of our own times. John supported Bradley Manning. Our work continues. Thank you, VVAW. Cindy Piester is a peace activist and supporter of VVAW.

|