|

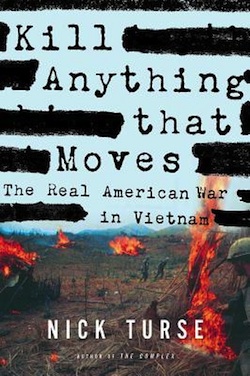

Kill Anything That MovesBy John Ketwig (reviewer)

Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam This book came to my attention via Truth-out.org, the on-line news and commentary site I trust as my primary source for awareness of what's happening in the world. Turse had been interviewed by Bill Moyers on his TV show Moyers & Company, and Truthout published a transcript of that interview. I immediately ordered a copy of the book, and read it with mixed emotions. First of all, I quickly recognized Nick Turse as the author of another book in my possession, "The Complex: How the Military invades Our Everyday Lives." I haven't had time to read that book yet, but I have browsed it, and I give Mr. Turse high marks for his ability to recognize the big picture. I left Vietnam in September of 1968. Instead of returning home to "the World," I transferred to nearby Thailand where I completed my military obligation. I avoided any possibility that I might be assigned to stand on the Pentagon steps and hold a bayoneted rifle against the anti-war protesters, and attempted to get my head straight enough that I would dare to walk down the street in my home town. Forty-four years after leaving Vietnam, I continue to have nightmares, anger, bitterness, and devastating sadness related to my war experiences. I was eager to read "Kill Anything That Moves," but I found I could only take it in small portions. Sometimes I could read a complete chapter in one sitting, but more often I had to put the book down and assimilate or digest the information. There is nothing new in Mr. Turse's book, but the sheer volume and detail of his reporting reveals in a harsh light that the few terrible moments that have haunted me all these years were not isolated instances at all, but mere threads in a huge tapestry. Turse acknowledges this head-on in his introduction. Yes, most Americans think of the massacre at My Lai when atrocities in Vietnam are mentioned, and the military's official position has been that that holocaust was an aberration. "The United States Army has never condoned wanton killing or disregard for human life," the army's director of military personnel policies, a Major General Franklin Davis, Jr. had assured one troubled vet back in 1971. It was, and is, a lie. Most Vietnam vets are painfully aware that the history of our war bears little resemblance to the reality of what we saw taking place all around us, but we carry that knowledge inside us like a cancer. It is terrible, not fit to be discussed at the dinner table, nor with friends while barbecuing in the back yard. We wait, always believing that there will be a better occasion to unburden ourselves, always hoping that someone will come along who might recognize the terrible importance of our fragments of memory to the vast mosaic that is American history in our lifetime. We read the newspapers, watch the TV evening news, and we become cynical as we wonder how the horrible truth has been ignored for so long. We will take our memories to our graves, still hoping that someday the truth might become known and accepted, even as the hopes slowly fade day by day. Nick Turse was a graduate student researching post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, when he stumbled upon the basis for this book. He was at the National Archives and finding little about PTSD when he asked an archivist for help. "Do you think that witnessing war crimes could cause post-traumatic stress?" the person asked, and Turse replied, "You know, that's an excellent hypothesis. What do you have on war crimes?" Within minutes he was looking at an expansive collection of data in cardboard boxes, a collection titled The Vietnam War Crimes Working Group Collection. In the wake of the My Lai massacre and the bad publicity that resulted, the Pentagon set up a task force in the Army Chief of Staff's office to track any war crimes allegations that might arise, and handle or spin them in a manner that would guarantee ongoing public support for the war effort. This was a huge collection of information relating to more than 300 investigations by the US military during the war, all related to allegations or reports of war crimes such as atrocities, massacres, mutilations, murders, tortures, assaults, and rapes. Turse was so moved by what he discovered that he left grad school to investigate this subject. He had no funding, no advance on a book, and no organization backing him. Fueled only by obsession, he traveled America to sit down with over one hundred veterans in their homes, or in hours-long telephone conversations, and hear their stories. His investigation led him to investigate other files at the National Archives, to request information under the Freedom of Information Act, and to interview generals and top civilian officials, and former military war crimes investigators. He made several trips to Vietnam, where he made his way to dozens of hamlets and villages to interview witnesses and survivors. "I'd thought I was looking for a needle in a haystack," he writes. "What I found was a veritable haystack of needles." "The scattered, fragmentary nature of the case files makes them essentially useless for gauging the precise number of war crimes committed by US personnel in Vietnam. But the hundreds of reports that I gathered and the hundreds of witnesses I interviewed in the United States and Southeast Asia made it clear that killings of civilians — whether cold-blooded slaughter like the massacre at My Lai or the routinely indifferent, wanton bloodshed? were widespread, routine, and directly attributable to US command policies. And such massacres by soldiers and marines, my research showed, were themselves just a tiny part of the story. For every mass killing by ground troops that left piles of civilian corpses in a forest clearing or a drainage ditch, there were exponentially more victims killed by the everyday exercise of the American way of war from the air." He continues, "There's only so much killing a squad, a platoon, or a company can do. Face-to-face atrocities were responsible for just a fraction of the millions of civilian casualties in South Vietnam. Matter-of-fact mass killing that dwarfed the slaughter at My Lai normally involved heavier firepower and command policies that allowed it to be unleashed with impunity." "This was the war in which the American military and successive administrations in Washington produced not a few random massacres or even discrete strings of atrocities, but something on the order of thousands of days of relentless misery -- a veritable system of suffering. That system, that machinery of suffering and what it meant for the Vietnamese people, is what this book is meant to explain." The above quotes are all from the author's introduction, and the book is relentlessly true to its aims. Mr. Turse exposes as never before the strategy of body counts, with accompanying competitions and incentives. Common grunts were awarded R & R (rest and recreation) days off for reporting enemy deaths, and higher-ups were awarded decorations, promotions, and career advancements. There was no concern for the Vietnamese who were dying by the millions. Turse calls this strategy overkill, and documents his case convincingly. "The notion that Vietnam's inhabitants were something less than human was often spoken of as the 'mere —gook rule', or, in the acronym-mad military, the MGR. This held that all Vietnamese — northern and southern, adults and children, armed enemy and innocent civilian — were little more than animals, who could be killed or abused at will. The MGR enabled soldiers to abuse children for amusement; it allowed officers sitting in judgment at courts-martial to let off murderers with little or no punishment; and it paved the way for commanders to willingly ignore rampant abuses by their troops while racking up 'kills' to win favor at the Pentagon." Again and again, the author quotes documents and records from the hidden files to substantiate his assertions. "American forces came blazing in with fighter jets and helicopter gunships. They shook the earth with howitzers and mortars. In a country of pedestrians and bicycles, they rolled over the landscape in heavy tanks, light tanks, and flame-thrower tanks. They had armored personnel carriers for the roads and fields, swift boats for the rivers, and battleships and aircraft carriers offshore. The Americans unleashed millions of gallons of chemical defoliants, millions of pounds of chemical gases, and endless canisters of napalm; cluster bombs, high-explosive shells, and daisy-cutter bombs that obliterated everything within a ten-football-field diameter; anti-personnel rockets, high-explosive rockets, grenades by the millions, and myriad different kinds of mines. Their advanced weapons included M-16 rifles, M-79 grenade launchers, and even futuristic technologies that would only later enter widespread use, like electronic sensors and unmanned drones. " The American military saw the battlefield in poor, agricultural Vietnam as a "laboratory" for new tactics and weaponry, and they threw everything at the war except nuclear weapons. (General Westmoreland begged permission to nuke Khe-Sanh in 1968, and President Johnson refused.) Ultimately, Turse says, American bombing dropped the equivalent of 640 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs upon Vietnam, an agricultural country approximately the size of Connecticut, and the majority was dropped upon our ally, South Vietnam. Civilian casualties were rarely avoided. This is an uncomfortable book to read. Page after page describes the horror in unflinching terms, and the scope of the devastation is overwhelming. He quotes veterans, observers, military data banks, and journalistic reports to inform us of the immense damaged inflicted. It is an illuminating and troubling book, and sobering. But this story has been told before, perhaps in less detail, and all of this sordid history has not affected the American military's blood lust whatsoever. Books such as "Our War: What We Did in Vietnam and What It Did To Us," by David Harris (1996), "US War Crimes in Vietnam," published in 1968 by the Juridicial Sciences Institute of the Vietnam State Commission of Social Sciences in Hanoi, "The New Soldier," by John Kerry and Vietnam Veterans Against the War (1971), "The Winter Soldier Investigation: An Inquiry into American War Crimes by Vietnam Veterans Against the War in 1972," "The War Behind Me: Vietnam Veterans Confront the Truth About US War Crimes," by Deborah Nelson (2008), "Going to Jail: The Political Prisoner," by Howard Levy, M.D. and David Miller (approximately 1970), "Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character," by Jonathan Shay, M.D., Ph.D. (1995), "Conversations With Americans: Their Shocking Stories of Being Trained in Torture Tactics and Their Accounts of Atrocities and Massacres They witnessed or Participated In" by Mark Lane (1970), "If This Be Treason" by Franklin Stevens (1970), "In the Service of Their Country: War Resisters in Prison," by Willard Gaylin, M.D. (1970), and "The New Winter Soldiers: GI and Veteran Dissent During the Vietnam Era" by Richard Moser (1996) are just a few of the very explicit volumes published and available on library or book store shelves during and since the war that the American people have largely ignored. Alas, I'm afraid "Kill Anything That Moves" will also be largely ignored, which is a shame. It is the best researched and documented history of the subject yet, by far, and a desperately important book in every respect. That said, I must point out that the book has its shortcomings. Very predictably, it has been criticized because it does not describe similar atrocities committed by the enemy in Vietnam. Yes, those atrocities did certainly happen, and they have been well documented elsewhere. Two wrongs don't make a right, and they are not relevant to the focus of this history. America still has not recognized that war itself is the common evil and to be avoided, in fact today's American society embraces militarism with far more passion than it did during the Vietnam tragedy or since! As this is written, a recent CBS 60 Minutes segment estimated that 22 American veterans are committing suicide every day, and the situation is getting worse despite all efforts to control it. Nick Turse has done us a great service by revealing that atrocities and overkill were "the American way of waging war" in Vietnam. But he discovered the evidence by accident when that nameless archivist asked if there might be a connection between witnessing war crimes and post-traumatic stress. There is ample evidence that America's "way of waging war" has not changed significantly since Vietnam, except that today's weapons are more terrible than anything we saw in Southeast Asia forty-some years ago, and today's military leaders are assured and emboldened by the fact that no one has yet been held accountable for atrocities committed by our troops in any combat situation since My Lai. If the suicide rate among veterans is a national tragedy of unprecedented proportions, Nick Turse has taken us to the very rim of the precipice and given us a long, hard look at the snakepit lurking below, but he has not acknowledged in any meaningful way what damage our "American way of waging war" did to our Vietnam veterans, and what the current continuation of those policies in Iraq and Afghanistan might be doing to today's American troops. He fell upon this material while researching PTSD, and it is a shame he does not tie the two subject matters together in any way. He acknowledges the importance of that archivist's question in his introduction, and tells us he has devoted more than ten years of his life to researching the subject, but he never answers the question! The truth should be obvious. Far too many of America's veterans are severely troubled by what they have seen or done in wars. Mental health "experts" are reluctant to acknowledge moral damage as an integral part of PTSD, as that recognition might discourage enlistments or defense appropriations. It has been half a century since our military won a war, and millions of the world's people have died horrible, needless deaths as the great American military machine grinds on. Today our militarism accounts for sixty cents of every dollar the American government spends, and our politicians want to cut Social Security, Medicare, health care, education funds, and even veterans' benefits to regain control. No one questions the military in today's America. Nick Turse has shone a bright light upon the sickness infecting America, and one can only hope that America will read this book and demand the wanton killing and torturing come to a halt. Wouldn't it be wonderful if the common phrase "Support our troops" might someday come to mean that we no longer allow our military to expose our patriotic, well-meaning soldiers to these types of horrors? Clearly, that is the author's intention in releasing this book to the American public, but his case might have been better made, not just implied. Vietnam veterans grew up in a different time. In those good old days, America stood for all that was good and just in the world. The Vietnam War was a tumultuous era in American history, and our nation changed drastically. "War is good for the economy," the protest posters read, "Invest your sons!" Today we have seen our manufacturing base abandoned or outsourced, with the obvious exception of the "defense industry". Our country is in the business of death and destruction, and business has been good. War profiteers buy influence in Washington, and flag-draped coffins come home to silent cemeteries in hometowns across the land. We know that civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan are suffering terribly, horribly, under America's assault. Meanwhile, President Obama has granted the Pentagon millions of dollars for a Vietnam War Commemoration Project that seeks to improve our appreciation of the "noble" aspects of the war. In a time of great economic and moral uncertainty, the "American way of waging war" might be far better served if copies of "Kill Anything That Moves" were placed in every library in the land. America's "way of waging war" is cruel and heartless, and "Kill Anything That Moves" is a sincere, honest, and hugely important attempt to rein in the bloodbath-for-profit that has been bankrupting our country both financially and morally for half a century or more. It is a compelling book, a dark secret brought into the light of day. Turse's prose is thoroughly accessible, his research exhaustive, and he has organized his material well. Perhaps the horrible history of America's tragedy in Vietnam has never been told better, but sadly I doubt that "Kill Anything That Moves" will become a great commercial success. John Ketwig is a lifetime member of VVAW, and the author of "...and a hard rain fell: A G.I.'s True Story of the War in Vietnam."

|