|

How King's Words "Lived" in Chicago, 1968By Dave DellingerI was asked by The Veteran to write about my memories of the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Let me say that two factors contributed to the atmosphere at that convention: first, the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. about four months earlier; second, the new-found radicalism of King, which probably caused his death. In response to his assasination there were widespread Black protests, including riots. Apparently the police in Chicago understood the reason for these activities and were more human and lenient than the reactionary Mayor Daley desired. So Daley berated them and issued orders that in any future disturbances the police should "shoot arsonists and looters - arsonists to kill and looters to maim." In the months between this order and the convention, the City kept asserting plans to shoot any violators of the City's streets, even nonviolent ones. The Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam and the Yippies tried for months to negotiate permits for nonviolent demonstrations. We were constantly denied the permits and threatened with extreme violence if we demonstrated without them. By contrast, a permit was issued to Senator Eugene McCarthy for a large-scale rally by his supporters. But as the time approached, the City used so much violence against local and regional anti-war demonstrators that McCarthy and his lieutenant, Allard Lowenstein, cancelled the rally and urged all demonstrators to stay home "in order to avoid bloodshed." In April 1967, Martin Luther King, Jr. for the first time spoke and marched against the war in Vietnam. By making this step and having been attacked for it by Ralph Bunche, a top Black American official at the United Nations, by the NAACP, the New York Times and many others, he radicalized the relatively conservative, top-down, mostly exclusive anti-racist approach that he had felt necessary to follow earlier. Now he began to organize a radical Poor People's Campaign that involved all oppressed peoples and called for radical changes in the elitist money economy. Here are some of the statements that he made during that Campaign; I cite them here because I referred to them every time I could during the 1968 convention: "For years I labored with the idea of reforming the existing institutions..., a little change here, a little change there. Now I feel quite differently. I think you've got to have a reconstruction of the entire society, a revolution of values." "We can't have a system where some people live in superfluous, inordinate wealth, while others live in abject, deadening poverty. From now on, our movement must take on basic class issues between the privileged and the underprivileged." "Something is wrong with capitalism as it now stands in the United States. We are not interested in being integrated into this value structure. Power must be relocated, a radical restructuring of power must take place." "The evils of capitalism are as real as the evils of militarism and evils of racism." "Nonviolent protest must now mature to a new level....mass civil disobedience....There must be more than a statement to the larger society, there must be a force that interrupts its functioning at some key point." Before the 1968 convention I did not know how many Vietnam veterans would be there. And I had hardly heard of VVAW. Its glory days began in the Spring of 1971 when members threw away their medals onto the steps of the Capitol. But we soon discovered our joint solidarity, not only against the Vietnam War but also in solidarity with the recent anti-capitalist views that King had articulated shortly before his assassination. Ever since, I have treasured VVAW and love to work with it as much as I can. Veterans have special insights that all of us need in our work for justice, human rights and an end to militarism.

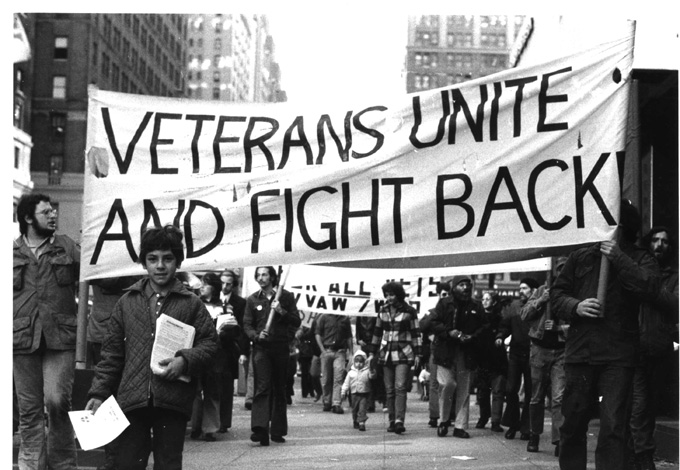

VVAW Veterans Day March, New York City, 1975

|