|

Remembering the Christmas BombingBy Interview with Barry Romo by Jen Tayabji

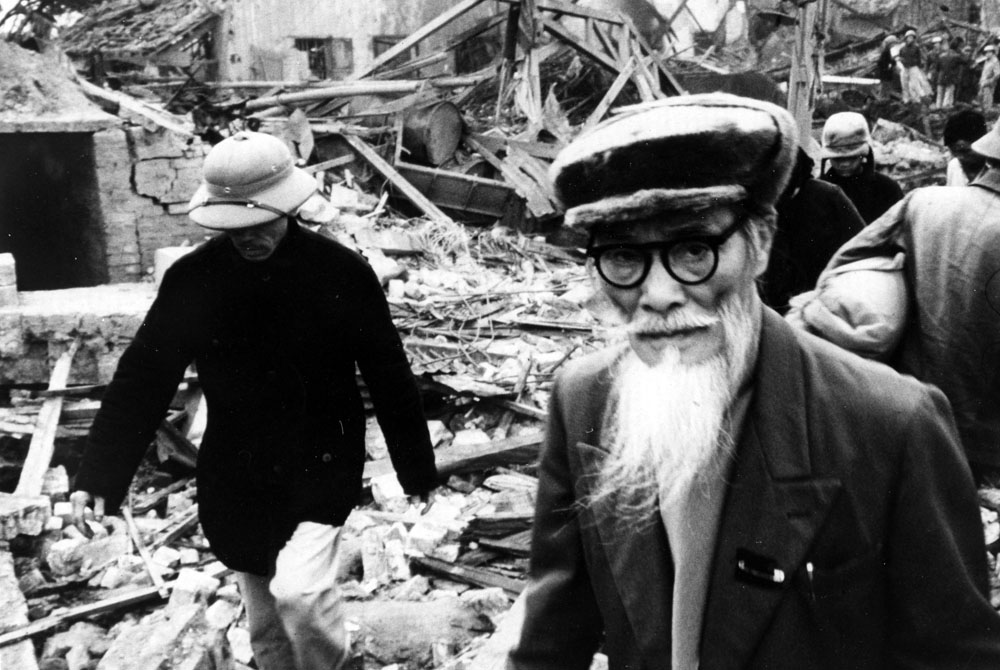

Forty years ago from December 18-29, 1972, the US carried out the largest aerial blitz in North Vietnam. After the breakdown of the peace talks in Paris, Operation Linebacker II started with 129 B-52s bombing Hanoi on the first evening. This bombing campaign lasted 11 days with a short break over Christmas. 741 B-52s, along with other fighter-bombers dropped over 20,000 tons of ordnance on Hanoi. By the end of the Christmas Bombing, thousands of homes and shops had been destroyed and at least 1,600 North Vietnamese killed. In December 1972, I went to Hanoi with Joan Baez, Rev. Michael Allen and General Telford Taylor. We were going to deliver Christmas packages and cards for US POWs from their families and to witness the damages from the war in North Vietnam. Many of you know of Joan, a well-known folk singer and human rights activist. She recorded parts of her album "Where Are You Now, My Son?" on this trip. Michael was the Assistant Dean of Theology at Yale at the time. Telford was a lawyer, professor, author and veteran. Before World War II, he worked as a lawyer. When the war started, he joined Army Intelligence and led the group who decoded intercepted German messages using ULTRA encryption. He served as both the Assistant to the Chief Counsel (then Robert H. Jackson) and the Chief Counsel for the US Nuremberg Military Tribunals. After the war, Telford taught International Law at Columbia University. He spoke out against McCarthyism and the Vietnam War. His book entitled, "Nuremberg and Vietnam: An American Tragedy," argued that the US conduct in Vietnam was as equally criminal as the Nazis conduct during World War II, based on the legal standards implemented at the Nuremberg trials. We left on December 11 and traveled for two days to get to Hanoi. As we flew to an airport outside of Hanoi, we could see craters marking the landscape. We were escorted to Hanoi. On the way, there was a convoy coming the opposite direction so we pulled off the road into a hamlet to let them pass. The railroad yard had been destroyed by bombings. But, there was a school not too far from it that had been untouched. The young school children came out to see who we were. We were clearly Americans. I had on Levis and Joan had her guitar. The school kids innocently sang us songs. Telford pointed out how the railroad yard had been destroyed yet the school was still here — there didn't seem to be signs of civilians being targeted, of war crimes. We met with our hosts in Hanoi to plan out our two-week-long trip. Tran Trong Quat with the Vietnam American Friendship Association had arranged our lodging and interpreter. We gave the Vietnamese the packages and cards from families back home that we had brought for the US POWs. We also gave them the blank video and photo film we brought. Because the war was still going on, they couldn't allow CBS to bring film crews, but they allowed us to bring them unexposed film from CBS so that they could record parts of our trip. They would develop the film and make sure they didn't reveal anything that US Intelligence shouldn't see. We understood. It was war. We started sight-seeing the first few days there. We went to Buddhist temples around Hanoi and also went to see areas that had been damaged from bombings. Late in the day on December 18, massive bombings began. There was so much confusion. We all thought — my travel companions and the Vietnamese — the war was coming to an end. But then the bombing started. Even after having served in South Vietnam, this was larger than any bombing raid I had experienced. The Vietnamese were prepared. They had a massive warning system using sirens. They also had built large rooms underground as well as these single-person tiny concrete foxholes throughout Hanoi. There were heavy-duty shields so the people could quickly get cover when needed. The raids were worse at night. We would go into the bomb shelter with the workers and other people staying at the hotel. The B-52s were so loud, when they dropped bombs, you could feel the earth move and grind. The shelters, being underground, only intensified the feeling of the earth grinding. It's hard to explain what it was like in the shelters. Everyone was on edge, just wanting the bombing to end so they could get out. And there were people from all different countries staying at the hotel so we couldn't really talk with each other. Sometimes after we all went into the shelter and I knew Joan, Michael and Telford were safe, I would go back up and sit outside behind the hotel and watch the planes. First, F-111s would fly in very low to the ground, so low that they could be shot down with machine guns. They were followed by the B-52s. During the day, we would still go sightseeing, but it was so much more limited now. The group that sponsored our trip, the Vietnam American Friendship Association, wanted to make sure we stayed safe so they were very careful about where we went. The Vietnamese really tried to clean up after the bombings, but there were a lot of people killed, blown apart. There were body parts scattered after each bombing raid. That's how hard Hanoi was targeted. During one of our trips out, we went to see Tran Quoc Pagoda, the oldest pagoda in Vietnam. Our interpreter broke down. He started shouting and screaming, "Why?" After the bombing started, the North Vietnamese said that we could photograph anything. They wanted the world to see what was happening. They wanted the pictures to show the truth — there were no secrets anymore.

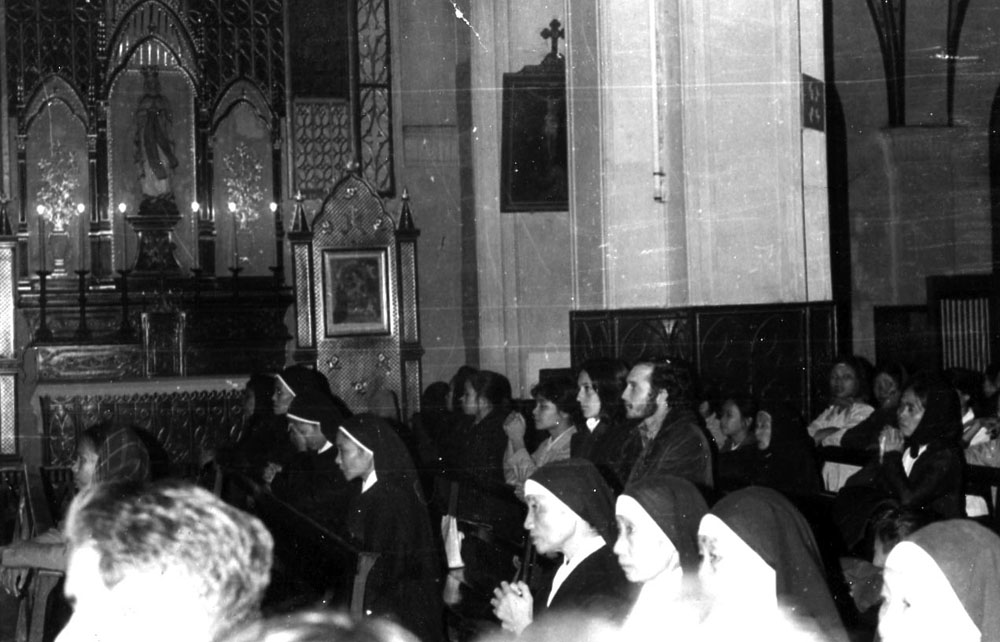

On Christmas Eve, Rev. Allen held a service for us. Joan sang for us. The bombing started again. Mr. Quat arranged for us to go to a Catholic Midnight Mass. He had never been to a Catholic service and wanted to understand what it was like. After Christmas, the North Vietnamese tried to get us out of the country earlier than planned. They drove us out to the airport to see if we could catch a plane. We went by the hamlet we stopped at on the way in to Hanoi. The school had been leveled, everything there had been leveled. There were no survivors. Telford had been very quiet on the trip and when we saw the decimated school, he shed a tear. Since we were unable to get out of the country, the North Vietnamese threw us a party. Despite being at war, having limited supplies, and being bombed, they found supplies to make us a cake. And we ate cake, drank and exchanged our cultures and experiences, songs and poems. Joan sang for everyone. They wanted us to share American culture. I didn't know what to say or share, but I had a prayer card with me from a friend's funeral, the Eight Beatitudes. I was overwhelmed. The pressure from the Christmas bombing raids, from my nephew's death, from what I saw in Vietnam, I started crying. The Vietnamese at the party took me aside. I started talking, sharing with Mr. Quat. I said, "My nephew died. My men died. I killed Vietnamese..." I didn't want to die by an American bomb. And it wasn't about dying, but to die at our own hands. I felt such a visceral hatred for Nixon and Kissinger for what they were doing to the Vietnamese. Quat said something to me I will never forget. "We know about your nephew. We knew your background before you came here... You know, your government took your precious idealism and they lied to you and sent you to Vietnam to kill Vietnamese people. And you killed people. But that's not important now. What's important now is that you suffer with the Vietnamese people. You can't blame yourself for what happened in southern Vietnam. The war is going to end. I know you don't believe me, but the war is going to end. And when it ends you are going to know peace like no other person. You are going to know the peace of a soldier who fought and killed in the south, but you are also going to know a Vietnamese peace because you suffered through the bombings with us in the north. You will know peace like no other." It brought me back to reality. It was just another night living under B-52 bombs. The next day, we went to Bach Mai hospital. It was the largest hospital in French Indochina. It was on every map. And it ended up being bombed three times. The day we went it had just been bombed for the second time. The doctors and nurses were digging with their bare hands through the rubble trying to find their patients. They had personally all lost so much, but they focused on their patients, on saving their patients, on keeping them from suffering. 600 people died. The first time the US bombed Bach Mai, they said there was no hospital there. The second time, they said that it was a first aid station. The third time the US said it was a hospital, but it was surrounded by MiG planes so they had to bomb it. I was there. We took photos. There were no MiGs. These were absolute lies. Finally, we were able to get out through the Chinese Embassy. After we met with them and we were waiting for the final word about leaving, we were back at the hotel. We were doing news interviews with the French press. And the bombings started again. The sirens went off. They knew I couldn't stand being in the bomb shelters, so we all waited out the bombing in the hotel room. Joan went on to the balcony, this tiny little balcony, and started singing civil rights songs with her guitar. Her voice carried through parts of Hanoi and people would clap. After that bombing raid ended and the electricity came back on, the people came and gathered outside the window to listen to and applaud Joan. The next day we were able to leave on a Chinese plane that was taking injured Polish sailors out of the country. These sailors had been stranded in a sunken vessel. They had been wounded and burned. We were waiting at the airport with the sailors and the bombing starts up again. So we went into the shelter. But the Polish sailors, who are still reeling from their vessel sinking, start to really freak out. Joan sang lullabies that she wrote for her son to help calm them down. Finally, the "all clear" siren goes off and we got onto the plane and flew to Guangzhou, China. We were some of the first Americans to be able to go into China then. We finally got back to the US when we flew into JFK airport on New Year's Eve, 1972. Barry Romo is a member of VVAW living in Chicago. Jen Tayabji is a community organizer living in Urbana, Illinois.

|