Download PDF of this full issue: v40n1.pdf (10.4 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v40n1.pdf (10.4 MB) |

Teaching Vietnam with the Class of 2012

By Janet Curry

[Printer-Friendly Version] Those of us working in classrooms are becoming aware that a generational page is turning again. Students now in the midst of their 10th grade year remember 9-11, but almost from beneath the usual level of consciousness, a foggy dread with a (somehow) flash point label. The killings at Virginia Tech might resonate with their periodic lock down drills, but recede in relation to Haiti and earthquake preparedness. At the Midwestern affluent suburban and voluntarily bus-desegregated public high school where I teach, Darfur was a cause taken up by older siblings and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are entirely misunderstood. Not only the Russian Revolution but the Soviet Union itself must be explained from scratch. The Cold War, typically taught as ending around 1990, apparently involved a protracted conflict between their home superpower and a group of pitiable countries scattered through Eastern Europe, South East Asia and Latin America, as if these latter had stubbornly insisted on hiring a cheap tutor and wound up with predictably substandard ACT scores. Marxism-Leninism, socialism, communism become synonyms for dictatorship. The capitalist business cycle is described over US history, but not comparatively analyzed. While most social studies curricula now make room for Vietnam within their 20th century coverage, the story tends to trail off somewhere around the US prediction of a bloodbath upon our 1975 departure. Vietnam's current low GDP, if mentioned, registers as a confirmation of its continued, willful cluelessness as it shuffles toward the free market.

With the Vietnam War increasingly a war of their grandparent's era, this is a generation that needs VVAW as a resource as much or more than any other so far, to help them analyze the instigation and the nature of the unfinished business between these two countries.

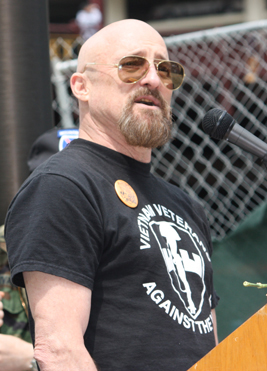

At my high school, the social studies department presents an annual day long, in-school field-trip known as Vietnam Day for the 10th grade. Outside academic and veteran speakers are invited and faculty from several disciplines join them in offering around 30 period-long session choices on a variety of topics. This year VVAW national coordinator Barry Romo covered two sessions on Vietnam and political activism. I prepared one on the leadership of Ho Chi Minh and one on Vietnam since 1975.

The opening session was given by an Air Cav vet, in Vietnam during Tet, whose story of white against black racism within US ranks referred to Vietnam only as a backdrop. Romo brought his students right into the heart of the war machine and up very close to interactions with the Vietnamese. He carefully traced his enlistment, the church and military's dehumanizing teachings, and how it felt to kill someone. He mentioned his Bronze Star for valor, complete with the friendly fire details left off the official citation. He talked about his nephew's Project 100,000 recruitment and eventual death in Vietnam. Romo also laid out how it was to try to return to civilian life, un-spat upon and in fact taken in by anti-war students who were drawn to arguing out positions with him. He detailed how he linked up with VVAW. He gave some history of VVAW, citing how they put together the personal and demographic pieces of PTSD; the hardscrabble and long haul fight to advocate for PTSD and Agent Orange recognition, compensation and treatment; the coalition work with SCLC, NAACP, International Tenants Association; can-canning on the Supreme Court steps; and how it was to commit to the organized activism that became the decades-long prerequisite for the Obama presidency.

During Q&A, students asked more about biographical narrative than wider issues, more about war stories and favorite weapons. Then came the questions that transformed the room: how is it to speak about the war and what is it like to have PTSD? Romo let them know it helps to speak the truth of it to power and to them. What they heard was that they are needed, as more than just listeners in a class, but as holders of truth, as emotional and/or political participants - right when they thought they were getting away with sliding straight into spring break. I know these students and you could see their eyes and postures shift to deal with the world becoming larger and more interesting. Dang they hate that.

Janet B. Curry is a high school teacher in the St. Louis area and a VVAW extended family member.

|