|

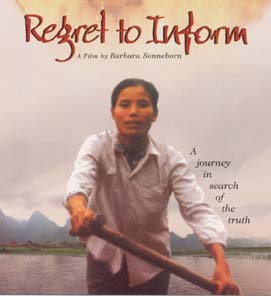

A Comfortable DistanceBy Edith Shillule (Reviewer)Regret to Inform, Barbara Sonneborn (Artistic License Films) There seem to be certain people and projects of which it is distasteful to be critical. War widows figure prominently in this category, so the position of those of us who do not admire the film Regret to Inform by Barbara Sonneborn is fraught with social hazard. In her documentary, Sonneborn journeys to Vietnam in an effort to forge meaning from her loss of her first husband, Jeff Gurvitz. She interviews war widows from both Vietnam and the United States, interspersing these interviews with images of contemporary Vietnam and powerful archival footage of American militarism. PBS promoted the work as a cry against the evils of war and - since it is funded in part by the president's initiative on race - as an educational film about the ways we "create" enemies. In the end, Sonneborn's artistry overwhelms the subject matter to keep us still at a comfortable distance from America's militarism, no closer to the unique suffering of war widows and nowhere near a full discussion of issues of class and race within a war context. What might have been an opportunity for a detailed look at catastrophe is a mere collage of the beautiful and the horrifying. Sonneborn has, however inadvertently, allowed us to again view war as a mysterious poison for which individuals, societies and governments are not responsible. This is not a film anti-war educators can fruitfully utilize in the classroom.

As the PBS press kit tries to get us to examine issues of race and enemy-making in its "facilitator's guide," it reveals Sonneborn's idealism but also the film's many missed opportunities. In it she writes, "My hope in making Regret to Inform is that by hearing these women's stories from both sides, viewers will begin to see that the enemy is war itself." Such popular mythology ignores militarist conditions that lead to war. Further into the narrative of the film there are virtually no comments about race, loyalty, nationalism, or divided loyalties, only the clipped presence of a diversity of American women. Worse still is the anonymity of the Vietnamese women. Nguyen Ngoc Xuan, Sonneborn's translator, gives extensive, heart-wrenching testimony, but women still in Vietnam appear and disappear without the recurrence of their names. While it seems natural that as a visual artist Sonneborn would rely on images to convey her message, the result of her choice is a collage of nameless faces and no genuine expression of the many layers of conflict that were brought to the surface of our societies by war. This keeps us at a comfortable distance from both American militarism and the divisive nature of Vietnamese nationalism. Sonneborn also gives the impression that she never experienced the painful, awkward conversations that many of us have seen and experienced as we continue to interact with the Vietnamese population. Friends in Hanoi gave me no such room for avoidance; why does Sonneborn give it to us? Was she never scorned by the southern Vietnamese for her liberal stance? Never rejected? Did she never receive e-mail like this from a Vietnamese journalist who complained: "I'm sick of Americans returning here with their 'war sickness' and I'm supposed to make them feel better." War reconciliation is all of these ugly and awkward conversations. "Regret to Inform" is a touching film in many ways, but we must not allow its merits to shore up what is clearly American complacency on notions of reconciliation. In short, the movie is good but it is not the vehicle for education and dialogue PBS hopes. We've looked at Vietnam for years and years as our own private war zone, but we're still not listening. Despite the personal testimony, we see the war as an uncontrolled poison when it was no such thing. The war destroyed hundreds of thousands of lives with grotesque violence. We have to say that this was done in OUR name and express not bewilderment and grief, but dissent. She is the author of Earth and Water: Encounters in Viet Nam (University of Massachusetts Press).

|

Journeying back to Vietnam to generate reconciliation is clearly a challenge. In her narration Sonneborn tells us that she is plagued by questions about Jeff's death, but does not tell us what they are or even what they are related to, thereby raising expectations that the film does not fulfill. Sonneborn relies too heavily on images to reveal both question and answer for the viewer. Her aloof stance as narrator is confusing for those who may be less informed about Vietnam and the war. Trying to work critically and creatively in a society as solicitous of your comfort as Vietnam is a challenge with which military veterans are painfully familiar, but Sonneborn fails to pursue reconciliation's harsh realities. Opening the PBS broadcast with a monologue explaining the project, she states that it was most difficult because she had to relive her grief, then adds that she had a hard time talking with Vietnamese women because she "had to ask them questions that made them cry more." Truthfully, she's one of a long line of Americans (and I was one of them) who walk into the lives of the Vietnamese clumsy, grieving, naive and stupid about the reality of their culture and the aftermath of our government's violence. Their public expressions of grief and our requests for them to relive trauma are so grossly voyeuristic that I find it akin to pornography.

Journeying back to Vietnam to generate reconciliation is clearly a challenge. In her narration Sonneborn tells us that she is plagued by questions about Jeff's death, but does not tell us what they are or even what they are related to, thereby raising expectations that the film does not fulfill. Sonneborn relies too heavily on images to reveal both question and answer for the viewer. Her aloof stance as narrator is confusing for those who may be less informed about Vietnam and the war. Trying to work critically and creatively in a society as solicitous of your comfort as Vietnam is a challenge with which military veterans are painfully familiar, but Sonneborn fails to pursue reconciliation's harsh realities. Opening the PBS broadcast with a monologue explaining the project, she states that it was most difficult because she had to relive her grief, then adds that she had a hard time talking with Vietnamese women because she "had to ask them questions that made them cry more." Truthfully, she's one of a long line of Americans (and I was one of them) who walk into the lives of the Vietnamese clumsy, grieving, naive and stupid about the reality of their culture and the aftermath of our government's violence. Their public expressions of grief and our requests for them to relive trauma are so grossly voyeuristic that I find it akin to pornography.