|

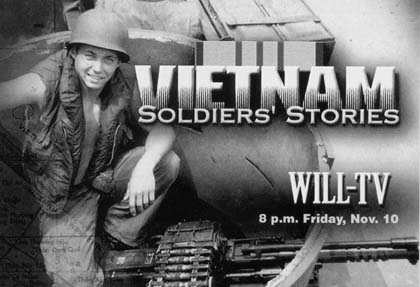

Notes From the BooniesBy Paul WisovatyIf everybody in the world is entitled to fifteen minutes of fame, then Barry Romo and I have each eaten up about three minutes of ours. We're not sure what we'll do with the twelve minutes we have left - if Barry ever lives to see them, what with that Colombia thing - but we do know about those first three. He and I were among thirteen Vietnam vets featured in a Champaign-Urbana PBS documentary called Vietnam: Soldiers' Stories, and if it hasn't been picked up by your local PBS station in Boston or San Diego, don't worry. We'll gladly send you a copy, for a modest fee plus shipping and handling. I hope that I may speak for Barry when I say that, at least at first, it was nice to be asked. Even though VVAW members made up only 15% of the vets interviewed, I believe that our readers will agree that all Vietnam veterans, whatever their political persuasion, have a right to express their opinions about the war. I very much mean that. Having offered that disclaimer, I will only note - with equal sincerity - that our opinions are the correct ones. (I never said living in The Boonies makes us humble.) When Tim Hartin, the show's producer, first approached me about this project in May 2000, he stated clearly that it was not his intention to do a "political" piece. Individual vets would be free to tell their stories, in their own words, and what they said was what got put on film. The questions from David Inge were excellent, and I'm certain that none of us ever felt that we were being "led" in one direction or another, or, as we say in the criminal justice system, cross-examined. Having said that, it will be apparent that, if thirteen vets were interviewed for about forty-five minutes apiece, and the final show consisted of about fifty minutes of veterans' statements, quite a bit got left out. In one sense, I have no problem with that. It was a one-hour documentary, and I suspect that some of the statements that I made in my forty-five minutes either didn't make any sense or, worse yet, caught me in a 50s moment when I completely lost my train of thought and just kind of sat there with my mouth open. (I do appreciate the fact that those were not included.) In another sense, it will be obvious that, if a producer has eight to ten hours of raw video footage to draw from, and which he has to trim down to less than an hour, he is both cursed and blessed. He is cursed in that he faces the enormous task of having to decide which 90% to leave on the cutting room floor, and which 10% to include in the final version. He is blessed in that he gets to leave 90% on the floor, and to include the 10% he likes. It is at this point that I have to start wondering exactly what happened here. As Joe Miller correctly pointed out, in his November 27 letter to the editor of the Champaign-Urbana News-Gazette, the documentary leaves the viewer with the conclusion that "there was no anti-war veterans' movement . . . GIs and veterans had nothing but hatred for the anti-war movement . . . (Barry Romo) does not get to tell how nearly 50,000 Vietnam veterans came home from our war to join VVAW and work with a welcoming peace movement." (The "welcoming" part is important; most Americans still believe that the customary treatment of returning vets, by anti-war types, was to spit on us at airports. We know that was in fact a rare occurrence, and that those who behaved in that fashion were not representative of the legitimate movement. Besides, by behaving that way, they also risked getting their heads broken. We were anti-war, but as Barry will tell you, that doesn't mean we were pacifists.) I cannot argue with one thing Joe said here. But I have to ask myself, as suggested above, "What happened here? How did WILL, the University of Illinois PBS affiliate, come to produce a film which, by commission and omission, presented that misleading picture to its viewing public?" I don't know. To play devil's advocate, we're not talking about the Armed Forces Radio Network, or Stars and Stripes. The Public Broadcasting System in this country has been for many years a poster child for the sort of media that Jesse Helms regularly decries, and demands that its plug be pulled. (I'm certain that Senator Helms is a regular subscriber to The Veteran, nonetheless.) In any case, anything Jesse doesn't like is awfully hard not to support. For the past couple of years, I have been a modest financial supporter of WILL, and I plan to continue that support. I have a really hard time imagining that three local PBS producers got together one day, after a long night of slugging down Chivas Regal and toasting George W. Bush, and said to each other, "We're really going to stick it to these liberal anti-war assholes." Like I said, I don't know why they did that, or perhaps more accurately, how they wound up doing it. Naive sort that I am, I don't even know if they know they did it. I suppose that one would just have to ask them, which I plan to do very shortly. (To be specific, I'm going to send them this column.) I do know, as do our readers, that there were up to fifty thousand Vietnam vets actively involved in the anti-war movement, which was unprecedented in the history of this country. I have also discovered, through multiple conversations with teenagers and even people my age, that this may be one of the best-kept secrets of 20th Century American history. I'm still looking for the first high school history book that mentions it. Most of them seem content to suggest that: "A lot of young Americans objected to our involvement in Vietnam." God only knows why, of course, because the authors seldom bother to burden their young readers with answers that might prove too confusing or depressing for them to handle. As I tell my high school students (Tuscola High School still invites me back each year, by the way), we were very much a decisive component in getting our country out of that war. Even when Nixon made us show our "good paper," we had that. Of course, a lot of honorable 'Nam vets also left with bad paper, for no good reason, which is another shameful aspect of that war. With regard to GIs' attitudes about the anti-war movement, I noticed one thing in the film I thought was particularly sad. One of the featured vets made the statement, referring to the Kent State murders (he didn't call them that), that for a lot of GIs in Vietnam, there was a part of them that said, "Good. It's about time those guys got theirs." He's right; a lot of vets felt that way thirty years ago, and a lot of them feel that way today. But most of us - at least, most of us in combat units - recognized that, as Yossarian said to a dangerously naive Clevinger in Catch-22, "the enemy is anybody who is trying to get you killed." Weren't nobody in the legitimate anti-war movement trying to get me killed, and I don't recall seeing Abbie Hoffman's name at the bottom of my draft notice. More importantly, leaving self-interest aside, the anti-war movement wasn't protesting only the fact that 58,000 Americans were in the process of getting wasted. They were objecting as much to the fact that two to three million Vietnamese, mostly civilians, were getting killed. Vets in the field, if not necessarily those stationed in base camps, knew that. We saw firsthand what our government was doing, and we supported the efforts of the home front anti-war movement to try and stop it. We realized that what we were doing was, to use an obscure legal term, a crime. Getting back to that veteran who made that statement about Kent State, I have to admit that I can't dismiss him as easily as I'd like. He's a Vietnam vet. Like most of us, he's still carrying around a lot of baggage, and he didn't ask for it and he didn't put it there. I think he's wrong, but I would never criticize him. I just wish he could come to grips with what we ("we" being not us vets, but the United States government) really did over there, because that might help him in his own healing process. I'm also afraid that that might be a long time in coming, and that the process will not be speeded up by documentaries like Vietnam: Soldiers' Stories, however well-intentioned they might be.

He lives in Tuscola, IL where he works for the Probation Department. He was in Vietnam with the U.S. Army 9th Division in 1968.

|